The Future of Faith

Tuesday, November 24, 2009 at 19:04

Tuesday, November 24, 2009 at 19:04 The wellsprings of faith upon which some of us draw may seem dry at times – even for longer than the typical instant of doubt that assaults all believers every now and then – dry, dusty and riddled with the scrapings of centuries of delusion. Perhaps living in an environment where your views are not contemned on a daily basis would aid the believer in his quest to find inner peace. Yet such isolation simultaneously robs him of something of undue importance: the humbug of the non-believer. The non-believer is an exceptional person. He has understood, to whatever degree, that he is not immortal, neither in body or soul, and has valiantly elected to carry on as if this realization – the most momentous realization at which a man can arrive – should not affect anything, from his morning ablutions to his nightly cocktails. One wonders what precisely drives such a person to rise from his bed and embrace his routine as the semblance of an existence. Oftentimes, it is material gain, which is the straight road of perdition; other times, the same mindless musings of which he so timorously accuses the believer ("all this is not real; all this is very real, but death is not real because death is not what we think it is; perhaps we are all already dead"); on other occasions it is the individualist's desire to separate himself from the masses and responsibility towards others. In my mostly pleasant traffic with self-proclaimed atheists and agnostics, their spineless cohorts, I have found this last scenario to be the most causative. Religion is a prison, an opiate, a necessary mirage to soothe the simple minds of the loitering rabble; religion enslaves, massacres and lies – as opposed, of course, to science, industrial capitalism, fascism, communism and any other movement that thinks it has all the answers. One day we shall have the cure for a coryza, and perhaps on that same eventful day our universe will reveal its inner workings to us at last. Until then, let the deluded and weary take comfort in essays such as the one above from this collection.

The future of faith has everything to do with its past. For the Abrahamic religions, that past might indeed extend to Adam's navel, or to a tree gilded by a slippery shadow, or the first homicide that released us into a den of thieves and killers, but science has indicated this is all plain hogwash. Numerous non-scientists have unwittingly buttressed the anticlerical movements ignited by, among other catastrophes, the French Revolution, and Updike produces to that end a lovely quote from a strange bedfellow's work:

The future of faith has everything to do with its past. For the Abrahamic religions, that past might indeed extend to Adam's navel, or to a tree gilded by a slippery shadow, or the first homicide that released us into a den of thieves and killers, but science has indicated this is all plain hogwash. Numerous non-scientists have unwittingly buttressed the anticlerical movements ignited by, among other catastrophes, the French Revolution, and Updike produces to that end a lovely quote from a strange bedfellow's work:

Our walk through Mantua showed us, in almost every street, some suppressed church: now used for a warehouse, now for nothing at all.

I know this book (it no longer sits, however, on my shelf) and should not be surprised. Christians march to Italy the way Muslims idealize Mecca, and the endless array of fountains and churches, the Vatican, the incomparable art, music and food all glorify the chosen seat of the Faith to millions of yearly visitors. How piteous, therefore, to consider for a moment the treasons committed and evils allowed in this same holy land. Updike recounts some of the blasphemies (often at the turn of each century; Updike was writing in 1999) that have usurped enough power and credence to become the rule rather than the outlier, and then gracefully intercedes with his own visit to Italy. He and his second wife take in the beautiful and eternal and nod in assent to both those qualities. When he opts to stroll through this famous museum, his wife commendably "decline[s] to waste her time on modern trash." What Updike finds in that shelter of gizmos, rebellion and utter talentlessness is amusing but also sad. Art is the reflection of a man's soul; from all indications the modern soul most closely resembles a graffitied toaster.

Updike also saunters through childhood memories, some rather frivolous because they are too intimate, and discovers the paradigms that structure his own faith. He is, after all, the grandson of a preacher and a lifelong churchgoer who, although an adherent to one Protestant church, had been a member of two others. He wisely passes over this indecision with the tacit admission that each venue serves the same purpose and, as it were, the very same Power. His attendance, seen by his consorts as "an annoying affectation," puts him squarely in the minority:

Belief in the afterlife is going up, even as church attendance drops. Attendance has been drifting lower ever since the baby boomers, joining churches as they began to generate families, started to wander away again. Though for decades polls have pegged the number of regular churchgoing Americans at around forty percent ... [it is estimated] that only twenty-eight percent of Roman Catholics attend Mass on a given weekend and fewer than one in five Protestants are in church on Sunday morning. Home study and the Sunday-morning religious shows on television are helping empty the pews. As part of the do-it-yourself trend, the sales of religious books have risen spectacularly, by fifty percent in the last ten years.

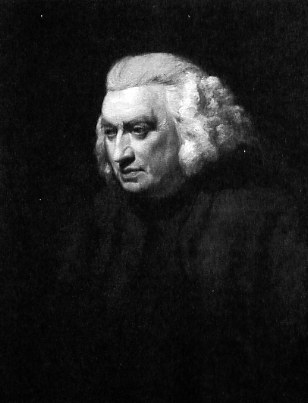

Such statistics belie the general tone of the essay, which is subjective, personal and saltatory. In fact, upon close inspection the whole affair reads as a disorganized clump, a tumbleweed grasping or lunging at random ideas of beauty and redemption (the most sensational being a Florentine thunderstorm). This confession from the "New Yorker's token Christian" is not nearly as organized as the systematic brilliance of this theologian or this great thinker – but religion commingles the unshakeable pattern of reason with the wildly sentimental disarrangements of the Romantic. In other words, if you can experience both within a short time, you can assert without fear of perjury that a sense for the religious is not alien to you. Updike also has an eloquent observation about his father's faith:

Where many fathers – some of them described in late-Victorian novels – conveyed to their sons an oppressive faith that was a joy to cast off, my father communicated to me, not with words but with his actions and his melancholy, a sense of the Christian religion as something weak and tenuous and in need of rescue. There is a way in which success disagrees with Christianity. Its proper venue is embattlement – a furtive hanging-on in the catacombs or at ill-attended services in dying rural and inner-city parishes. Its perilous, marginal, mocked existence serves as an image of our own, beneath whatever show of success can be momentarily mustered.

That we are embattled needs little discussion; that success is too often defined by everyone's definition except your very own continues to baffle people until they become old, grey and unsuccessful. But that the way of the Lamb can use whatever strength we can grant it should be reason enough to wonder about the meek and our future inheritance.