Aes Triplex

Sunday, November 8, 2009 at 22:30

Sunday, November 8, 2009 at 22:30 After a certain distance, every step we take in life we find the ice growing thinner below our feet, and all around us and behind us we see our contemporaries going through. By the time a man gets well into the seventies, his continued existence is a mere miracle; and when he lays his old bones in bed for the night, there is an overwhelming probability that he will never see the day. Do the old men mind it, as a matter of fact? Why, no. They were never merrier; they have their grog at night, and tell the raciest stories; they hear of the death of people about their own age, or even younger, not as if it was a grisly warning, but with a simple childlike pleasure at having outlived someone else; and when a draught might puff them out like a fluttering candle, or a bit of a stumble shatter them like so much glass, their old hearts keep sound and unaffrighted, and they go on, bubbling with laughter, through years of man's age compared to which the valley at Balaclava was as safe and peaceful as a village cricket-green on Sunday. It may fairly be questioned (if we look to the peril only) whether it was a much more daring feat for Curtius to plunge into the gulf, than for any old gentleman of ninety to doff his clothes and clamber into bed.

Those of artistic bent face a quandary that, compared to the perdition looming over so much of the world's population, may seem petty. When we are young and unsung there are few who will heed our opinions. Our parents and teachers smile at our sudden discovery of age-old platitudes, while the women we seek to impress cannot possibly be impressed with the unsteady observations of callow manhood. As time progresses we marry and procreate, become greater experts in whatever field we have chosen either provisionally or as a simple means of sustenance until we blossom as artists, and if we are not careful, we wake up one morning and find ourselves no longer young. Around us walk members of a whole new generation that consider us nothing more than martinets of stale values and ideals; if they're particularly rebellious, they will even deride our playfulness as inappropriate. To all this, of course, we nod our heads and remember our own churlish gibes at our elders, part and parcel of becoming authorities on what it means to live. Yet what no one can hold forth on with any credibility is the end of days, how life resolves itself either into nothingness or something greater still. And how we should approach our evenings is the subject of this famous essay.

The most important thing about death is that we have no contrast for its understanding. Life as we know it is not really life, but the pursuit of living – be that living wildly or quite prudishly with one eye cast above to the gathering clouds. We continue nevertheless to prattle on about life in the most abstract terms as if it were a recipe or an amorphous mass of an invisible element, which is precisely what bothers Stevenson:

The most important thing about death is that we have no contrast for its understanding. Life as we know it is not really life, but the pursuit of living – be that living wildly or quite prudishly with one eye cast above to the gathering clouds. We continue nevertheless to prattle on about life in the most abstract terms as if it were a recipe or an amorphous mass of an invisible element, which is precisely what bothers Stevenson:

In taking away our friends, death does not take them away utterly, but leaves behind a mocking, tragical, and soon intolerable residue, which must be hurriedly concealed .... and, in order to preserve some show of respect for what remains of our old loves and friendships, we must accompany it with much grimly ludicrous ceremonial, and the hired undertaker parades before the door. All this, and much more of the same sort, accompanied by the eloquence of poets, has gone a great way to put humanity in error; nay, in many philosophies the error has been embodied and laid down with every circumstance of logic; although in real life the bustle and swiftness, in leaving people little time to think, have not left them time enough to go dangerously wrong in practice.

A cursory glance at these words and further inspection of the essay should not result in the indifference so commonly incident to daredevils and other defiers. Practice has been to worship those we loved, and that practice will never stop, at least inwardly. But as children, a stage of life that greatly concerned Stevenson, we are told and shown a plethora of rituals that, as we age, do not necessarily become more intelligible. Surely a blessing for safe passage is clear even to the greenest among us, but what of wakes, cremation, or burial among the filth we scrape daily off our shoes? What possesses a society to exalt the enskied spirits of our beloved if we rudely dispose of their former forms? This is no place for comparative anthropology on death rituals – a subject that always seems to infiltrate college curricula – so let us but roam amidst an infirm Scotsman's preset boundaries.

Death has its admirers, normally those among us who either seek exculpation from their sins or a release from what they perceive as unending torment. The monk who beseeches his Lord to do away with his sullied body so that his soul may be clean is worthy of both our respect and pity; and those poor mortal coils who take matters into their own hands deserve even greater remorse. But Death lingers on as the most impenetrable of human mysteries because it sustains more readings than life. Ask a physician about our terminus and he will point to diagrams and x-rays; ask a theologian and he will nod in grave acceptance of our Fate; ask a soldier and he will see battlefields strewn with his companions, fallen but never forgotten; ask a very old man and you may notice a sadness as all of life flashes behind his eyes. As the highest form of human expression, it is literature which assumes the task of imagining death most explicitly, and we do so by "rising from the consideration of living to the Definition of Life." Death becomes what will be taken away and, in the view of some, never replaced:

Into the views of the least careful there will enter some degree of providence; no man's eyes are fixed entirely on the passing hour; but although we have some anticipation of good health, good weather, wine, active employment, love, and self-approval, the sum of these anticipations does not amount to anything like a general view of life's possibilities and issues; nor are those who cherish them most vividly, at all the most scrupulous of their personal safety. To be deeply interested in the accidents of our existence, to enjoy keenly the mixed texture of human experience, rather leads a man to disregard precautions, and risk his neck against a straw. For surely the love of living is stronger in an Alpine climber roping over a peril, or a hunter riding merrily at a stiff fence, than in a creature who lives upon a diet and walks a measured distance in the interest of his constitution.

Death, we recall, "outdoes all other accidents because it is the last of them"; after that some might say that there are no accidents, only destiny. Yet as we pass middle age and move gently into that good night, we may have prudence and caution as our only bedfellows. We may desist in any acts of generosity and instead devolve into an insular being surviving against the rest of the predatory world. That survival has so casually come to replace life in common parlance among men of science says much about the world that now surrounds us: we have relinquished any hope for salvation and put our efforts into genetic experiments that may prove to be the greatest catastrophe we will have ever wrought upon mankind. Already in Stevenson's age and shortly thereafter there appeared scientists (including this scholar who inspired more than one literary understudy) who felt untouched by God's hand and yearned for a reality they could fashion in the image of our most perfect beast. What you may think of these would-be creators will probably reflect what you think about our ultimate destination – but that is a subject best left to one's own conscience.

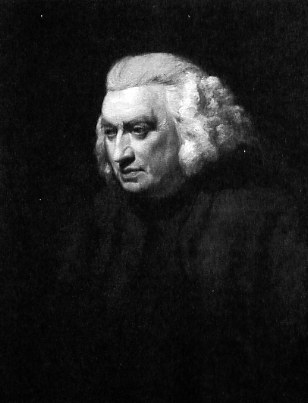

The title of the essay is from a citation by this Roman writer, but applied in anecdote to an English lexicographer and critic whose weighty step still resounds in our best libraries. One may chuckle at the famously elephantine Johnson garbed in three layers of brass, but one should remember where he was at the time: roaming the Scottish highlands, ill of health, and accompanied, as one now imagines always to have been the case, by another Scotsman named Boswell. A model of "intelligence and courage" to expose oneself to such a climate when many a physician had already surmised the end to be near. But for some of us, our beginning is in our end.

Reader Comments