The Talented Mr. Ripley (film)

Friday, November 7, 2008 at 00:12

Friday, November 7, 2008 at 00:12 Modern critics will be happy to tell you that the best works of literary (and, for that matter, cinematic) art are those which yield numerous interpretations. For them, the wonderful thing about modernity's sad indecisiveness is that it parallels their own: nothing has any one meaning, thus stripping the critic of his responsibility to understand a work on its own terms. You will find the most egregious offenders in this regard among those who read philosophy as if they were reading a novel, chopping and picking at whatever appeals to them to formulate their own theories that, upon closer inspection, turn out to distort and disrupt the original. Does a poem by Cavafy have the same significance if read by a Greek or a Chinese speaker? Certainly not; yet Cavafy possesses, as all good writers do, a certain frame of reference that might be simplified as his cultural context, but which in the final analysis is nothing more than his own moral structure. Regardless of where his readers may hail from, Cavafy will ultimately be judged on his ability to delineate right from wrong and convince us that his particular delineation adds to our knowledge of this difference. If nothing matters to him, it surely will not be worth a damn to us. My mentioning Cavafy is not a coincidence, nor are any of the details pertinent to the plot of this film.

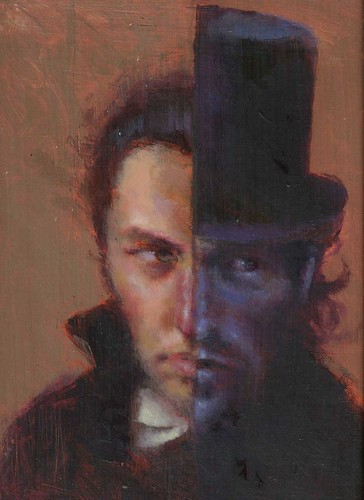

Our protagonist is a certain Thomas Ripley (Matt Damon), a moody, artistic youth who obviously has never had the opportunities of many other, far less talented coevals. His surname might have something to do with this phenomenon whose founder died at the peak of his renown a few years before Highsmith's book was published; yet more important is his Christian name, which in Aramaic means "twin." What we will witness, with the slow precision of a crime planned years in advance, is the twinning of paths, the old and familiar fable of the double: the first path will be the simple, straight road of guaranteed luxury; the second the sinuous struggle of a very intelligent but impoverished young man. Ripley is playing the piano at a social function when he is approached by Herbert Greenleaf (James Rebhorn), a moneyed businessman who assumes quite logically that Ripley's Princeton jacket must mean he went to Princeton, and that if he went to Princeton, he must certainly know his famously wayward son, Dickie Greenleaf. Ripley's response to Greenleaf's conversation sets the tone for the film: he lies, but doesn't simply agree to his mistake, he moves a step further and knowingly asks, "How is Dickie?" Those three words grasp Greenleaf's weakness in its totality. And the consummate businessman does what only very rich and arrogant people are accustomed to doing: he tries to purchase Ripley's services and dispatch him to bring his son back from Europe. Most young men with an easy past and a bright future might find this assignment somewhat humbling; but most young men with an easy past and bright future also have the indelible tendency of never having enough money to satiate their whims. This Ripley fellow, however, is different. He is humbler, more sensitive and artistic, probably close to his money, a responsible youth who will go very far. So when, from a distance, he sees Ripley embrace a girl outside the club and hand over his Princeton jacket, Greenleaf cannot imagine that the girl is not Ripley's significant other, or that the jacket and Princeton degree actually belong to her boyfriend. Greenleaf sees only what he wants to see; we, the viewers, see the truth as well, as we will at every step of Ripley's journey.

Our protagonist is a certain Thomas Ripley (Matt Damon), a moody, artistic youth who obviously has never had the opportunities of many other, far less talented coevals. His surname might have something to do with this phenomenon whose founder died at the peak of his renown a few years before Highsmith's book was published; yet more important is his Christian name, which in Aramaic means "twin." What we will witness, with the slow precision of a crime planned years in advance, is the twinning of paths, the old and familiar fable of the double: the first path will be the simple, straight road of guaranteed luxury; the second the sinuous struggle of a very intelligent but impoverished young man. Ripley is playing the piano at a social function when he is approached by Herbert Greenleaf (James Rebhorn), a moneyed businessman who assumes quite logically that Ripley's Princeton jacket must mean he went to Princeton, and that if he went to Princeton, he must certainly know his famously wayward son, Dickie Greenleaf. Ripley's response to Greenleaf's conversation sets the tone for the film: he lies, but doesn't simply agree to his mistake, he moves a step further and knowingly asks, "How is Dickie?" Those three words grasp Greenleaf's weakness in its totality. And the consummate businessman does what only very rich and arrogant people are accustomed to doing: he tries to purchase Ripley's services and dispatch him to bring his son back from Europe. Most young men with an easy past and a bright future might find this assignment somewhat humbling; but most young men with an easy past and bright future also have the indelible tendency of never having enough money to satiate their whims. This Ripley fellow, however, is different. He is humbler, more sensitive and artistic, probably close to his money, a responsible youth who will go very far. So when, from a distance, he sees Ripley embrace a girl outside the club and hand over his Princeton jacket, Greenleaf cannot imagine that the girl is not Ripley's significant other, or that the jacket and Princeton degree actually belong to her boyfriend. Greenleaf sees only what he wants to see; we, the viewers, see the truth as well, as we will at every step of Ripley's journey.

It turns out that Dickie (Jude Law), being the smart boy he is, has made his way to Italy with a pretty young thing named Marge Sherwood (Gwyneth Paltrow), and his plan is to have no plan at all. Ripley tracks down the couple, ingratiates himself with the mistake provided by Dickie's father, and soon is sharing in the Byronic decadence that Dickie has so pathetically misidentified as the freedom of youth. Yet it is on his way to Europe by ship that we first catch a glimpse of Ripley's real intentions. Upon meeting a young woman named Meredith Logue (Cate Blanchett) – another bored rich person who doesn't quite feel guilty about her easy life as much as annoyed that she knows she should feel guilty – Ripley introduces himself as Dickie. Should we nod our politically correct heads at his obvious envy of Dickie's privileges? Should we snicker at the pun on "Tom and Dick," the original form of the catch-all expression, "Tom, Dick and Harry," which was incipiently a reference to two working-class youths from Bow and Whitechapel? Should we understand Ripley's lie as an attempt to bed Meredith, who is rich and attractive and more than a little naïve? Were this a more typical tale of the inequalities of postwar Europe and America exemplified by the ideological war of socialism and capitalism, the answers to these questions might all be yes. But they are not yes. We are not confronting rich and poor in an allegory of societal malfeasance and Tom Ripley couldn't care less about Meredith or any other woman. The only person for Tom, you see, is Dickie Greenleaf.

For better or worse, the film runs through the permutations of understanding Ripley's motives with sufficient objectivity. When Dickie asks what makes Ripley special ("everyone should have one talent") and Ripley replies that he is particularly skilled at "forging signatures, telling lies, and impersonating practically anyone," we are led to believe that Ripley is evil. Until we realize, perhaps, that deception is a stereotypically feminine trait, and coyness and an unwillingness to give a straight answer the signs of the coquettish woman who will never directly express her desires. When a loud, hedonistic boor by the name of Freddie Miles (Phillp Seymour Hoffman) comes racing into town, Ripley hasn't the slightest desire to join the jetset, make love to every woman he sees, or stumble about in the drunken bubble of irresponsibility that is the calling card of wealthy foreigners living the sweet life. No, what he wants is for Freddie to get as far away as possible from Dickie. Soon enough, Dickie's true character is revealed through not-so-clandestine arguments with the lovely daughter of a local shopowner, his utter lack of ability in anything useful, creative or smart, as well as Marge's running commentary:

The thing with Dickie is that ... when you've got his attention, you feel like you're the only person in the world... it's like the sun that shines on you and it's glorious. And then he forgets you and it's very cold.

Ripley, of course, being the sedulous listener that he is (all good impersonators are very good listeners), knows all this, but continues to hope that he will prove to be the exception. And so, the first and most damning crime takes place one beautiful fall day in Sicily (November 7, we learn later from the police report) and Tom finally gets to become Dickie to everyone who didn't know him, exactly, as it were, halfway through the film. It has taken him that long to find, catch, and replace Dickie, who did not share his interests or affection; and it will take the film's remainder to make sure that no one learns of the switch, that Dickie's foul temper and general lack of culture will make him an easy frame for other misdemeanors, and that even those who knew him would bow their heads in sullen acceptance of his world gone wrong. But we viewers see the duel, as Meredith and Ripley attend this legendary opera featuring another tragic duel between friends, and we know what Tom Ripley wants: "to be a fake somebody rather than a real nobody." If only Dickie Greenleaf were somebody worth being.