Robert Louis Stevenson

Thursday, April 28, 2016 at 10:27

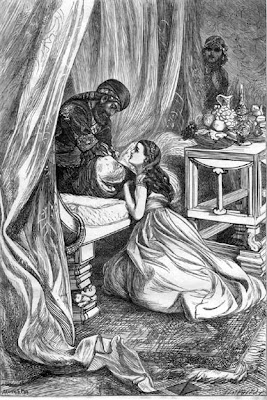

Thursday, April 28, 2016 at 10:27 The most really Stevensonian scenes, in their spirit and spitfire animation, are those which occur first in the prison.

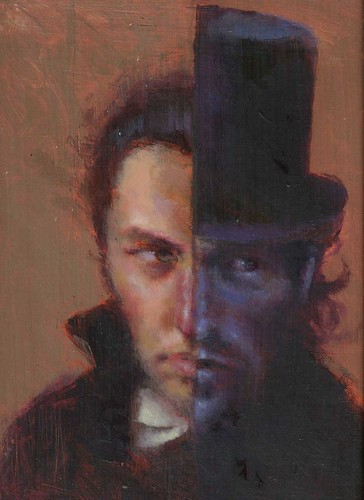

When I was in graduate school, one of my professors casually mentioned that he had been named for this writer whom, he implied, he was obliged to hold in high esteem. That he did not particularly care for Stevenson and was instead enamored with Russian writers whom he found infinitely more exotic than a shaggy-haired Scotsman who would suddenly die while mixing an exotic salad in the South Pacific, seems hardly surprising given that Stevenson is often seen as nothing more than a children's writer with success among adults. One of my favorite books as a child was this magical tome, and many of my coevals (but not I, for some reason) reveled in this classic tale whose villain became the name of a chain of budget seafood restaurants. Yet the most famous of Stevenson's creations, and the ones which have passed into common idiom, are the titular characters of this story, even though the two characters are actually the sum of one man. For that reason perhaps has modern criticism been rather harsh with Stevenson: he has been accused in reveling in boys' tales, children's worlds of fancy and monsters and pirates, and for never really developing a serious brand of literature to meet our serious tastes. Indeed, the same mudslinging that is pitched at this bestselling series (which, despite its massive adult readership, is intellectually designed for adolescents) has been the bane of Stevenson scholarship since his premature death in 1894. There have been encomia and anthologies, but few have been gracious or understanding. Maybe his stoic Scots wit lies at the center of this neglect; maybe Stevenson simply did not live long enough to manifest the true signs of his genius. One rather remarkable biography agrees with the first point but not the second.

When I was in graduate school, one of my professors casually mentioned that he had been named for this writer whom, he implied, he was obliged to hold in high esteem. That he did not particularly care for Stevenson and was instead enamored with Russian writers whom he found infinitely more exotic than a shaggy-haired Scotsman who would suddenly die while mixing an exotic salad in the South Pacific, seems hardly surprising given that Stevenson is often seen as nothing more than a children's writer with success among adults. One of my favorite books as a child was this magical tome, and many of my coevals (but not I, for some reason) reveled in this classic tale whose villain became the name of a chain of budget seafood restaurants. Yet the most famous of Stevenson's creations, and the ones which have passed into common idiom, are the titular characters of this story, even though the two characters are actually the sum of one man. For that reason perhaps has modern criticism been rather harsh with Stevenson: he has been accused in reveling in boys' tales, children's worlds of fancy and monsters and pirates, and for never really developing a serious brand of literature to meet our serious tastes. Indeed, the same mudslinging that is pitched at this bestselling series (which, despite its massive adult readership, is intellectually designed for adolescents) has been the bane of Stevenson scholarship since his premature death in 1894. There have been encomia and anthologies, but few have been gracious or understanding. Maybe his stoic Scots wit lies at the center of this neglect; maybe Stevenson simply did not live long enough to manifest the true signs of his genius. One rather remarkable biography agrees with the first point but not the second.

There are many ways to approach Stevenson's oeuvre, and Chesterton is convinced they are all wrong. "The story of Stevenson," he writes, "was a reaction against an age of pessimism." Stevenson was born at almost precisely the median point between the publication of two books, The Voyage of the Beagle and On the Origin of Species, that would change our perspective on what it meant to be human; if this were not sufficiently disastrous, Stevenson was also born in Scotland. More than mild chauvinism coats the backhanded compliments that Chesterton hurls at his northern brethren ("A Scotsman is never denationalized"; "There is something shrill, like the skirl of the pipes, about Scottish laughter; occasionally something very nearly insane about Scottish intoxication"; "The Scots are in a conspiracy to praise each other"), and it is this "Presbyterian country, where still rolled the echoes, at least, of the theological thunders of Knox," that framed Stevenson's window on the world. Over his short lifetime Stevenson abandoned his faith to a great extent but retained his categories; in fact, he retained them so strongly as to make any real difference between his rhetoric and that of a Kirk pastor purely one of vocabulary:

Those dry Deists and hard-headed Utilitarians who stalked the streets of Glasgow and Edinburgh in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were very obviously the products of the national religious spirit. The Scottish atheists were unmistakable children of the Kirk. And though they often seemed absurdly detached and dehumanised, the world is now rather suffering for want of such dull lucidity.

This detachment, this streamlined austerity, this "economy of detail and suppression of irrelevance which had at last something about it stark and unnatural" – this was how Stevenson built his world that was both varied and thematically coherent. Gone are the comparisons to this writer (whose atmosphere Chesterton aptly describes as "a sort of rich rottenness of decomposition, with something thick and narcotic in the very air," a perfect account of hell), and provided are likenings to no one else because, as it were, Stevenson has no true peer.

In fact, his combination of childish tenderness and zeal – hence the suppression of irrelevance – with the dark materials of adult interaction could be laughed at as puerile or praised as visionary. Chesterton suggests the latter course, for one very good reason:

But most men know that there is a difference between the intense momentary emotion called up by memory of the loves of youth, and the yet more instantaneous but more perfect pleasure of the memory of childhood. The former is always narrow and individual, piercing the heart like a rapier; but the latter is like a flash of lightning, for one split second revealing a whole varied landscape; it is not the memory of a particular pleasure any more than of a particular pain, but of a whole world that shone with wonder. The first is only a lover remembering love; the second is like a dead man remembering life.

In contrast to so many literary biographies which underscore "real-life" events over the works in the author's library because most every reader can empathize with childhood, adolescence, marriage, heartbreak, children, aging, and even the death of a relative or friend, Chesterton's discusses Stevenson's works with occasional allusions to his life (the exact same biographic method used in this fine study). Stevenson's life is not particularly well-known (a dearth of detail has never stopped an imaginative biographer), and Chesterton farrows no new animalia in this distant kingdom; rather, he begins with "The Myth of Stevenson" and ends with "The Moral of Stevenson," as if a retelling of his life were something like a fable. He explores Edinburgh but makes almost no mention of those Pacific islands; he speaks of style but not in comparison to anyone else's, as if Stevenson's style were a reflection of his unique childhood; he suggests a philosophy of gesture in the sense of a chanson de geste; and he quibbles not unconvincingly over Stevenson's reaction to romance and Romanticism, although Stevenson was undoubtedly a Romantic if a rather meticulous one. And what is most remarkable is how little Stevenson himself is quoted, with one of his more famous lines being clipped into a short phrase.

Chesterton is more interested in Stevenson's books than his life not only because his books were deceptively demanding and literate, but also because for all authors – and especially Stevenson who spent most of his waking hours as a convalescent in the prison of his bedroom – their real life is in their books. Their biographies are not those of ordinary men because to achieve their artistic ends they forsake much of the lowlier stuff life has to offer. In our day and age these activities would include: television, video games, touristic vacations of mindlessly banal but often scenic resorts, magazines, gambling, motorcycles, drugs, hunting, and a variety of expensive, time-consuming, and exhausting sports. In their stead would come daily reading and writing, long walks, sitting and staring at what nature mankind has left unharmed, talking warmly to loved ones and cherishing each moment as if separation were imminent, laughing at the silliness and fraudulence of the world, and loving what we have and what we might have in the future. But most people would find such a life devoid of intrigue and let it sit, unsurveyed, upon a dusty shelf like so many of Stevenson's works sit now in all the old libraries of the world. What a mistake that would be.