A short story ("Adrift") by this Uruguayan writer. You can read the original here.

The man trod on something off-white, immediately felt a bite on his foot, and leapt forward. Upon turning and swearing, he espied a lancehead – what the locals call a yaracacusú – coiled upon itself in anticipation of another attack. Taking a quick glance at his foot, where two drops of blood were swelling troublesomely, the man removed the machete from his belt. The viper saw the threat and sank its head deeper into the center of its coil; but the machete crashed down upon its spine, dislocating its vertebrae. He bent over closer to the bite marks, wiped away the drops of blood, and thought about matters for a moment. An acute pain had emerged from those two purple dots and begun to invade his entire foot. In haste he bound his ankle with a handkerchief and followed the path back to his ranch. The pain in his foot was increasing, along with a sensation of tense swelling, and suddenly the man spotted two or three shiny stitches irradiating like lightning from the wound to the middle of the calf. He could move his leg only with difficulty; his throat was afflicted with metallic dryness then insatiable thirst, and he swore anew under his breath.

The man trod on something off-white, immediately felt a bite on his foot, and leapt forward. Upon turning and swearing, he espied a lancehead – what the locals call a yaracacusú – coiled upon itself in anticipation of another attack. Taking a quick glance at his foot, where two drops of blood were swelling troublesomely, the man removed the machete from his belt. The viper saw the threat and sank its head deeper into the center of its coil; but the machete crashed down upon its spine, dislocating its vertebrae. He bent over closer to the bite marks, wiped away the drops of blood, and thought about matters for a moment. An acute pain had emerged from those two purple dots and begun to invade his entire foot. In haste he bound his ankle with a handkerchief and followed the path back to his ranch. The pain in his foot was increasing, along with a sensation of tense swelling, and suddenly the man spotted two or three shiny stitches irradiating like lightning from the wound to the middle of the calf. He could move his leg only with difficulty; his throat was afflicted with metallic dryness then insatiable thirst, and he swore anew under his breath.

Having arrived finally at the ranch, he threw himself atop his mill-wheel. Now the two purple points were vanishing into the monstrous lump the whole foot had become. There his skin appeared thinner, tenser, and about to crack He wanted to call out to his wife, and his voice broke into a hoarse scratch. Thirst was devouring him.

"Dorothea!" he managed to rattle. "Bring me a beer!"

His wife came running with a full glass, which the man drank in three gulps. But he did not taste a thing.

"I asked you for beer, not water!" he roared again. "Bring me a beer!"

"But it is beer, Paulino," protested the woman, quite scared.

"No, you brought me water! I want beer, I tell you!"

The woman ran off one more time and returned with a demijohn. The man had another glass, then two more, but he felt nothing in his throat.

"Alright, this here is getting very bad," he muttered, looking at his livid foot which already boasted the shine and luster of gangrene. Atop the handkerchief's heaping ligature, flesh was oozing out like some monstrous pudding.

Shooting pains were followed by further lightning stitches which now reached his inner thigh. At the same time, the atrocious dryness in his throat, which breathing only seemed to heat up and exacerbate, was growing. When he tried to stand up he vomited instantly, forcing him to remain for half a minute with his forehead pressed against the wheel's spoke. But the man did not want to die, so he went down to the shore and got in his canoe. He sat down at the stern and began to paddle towards the center of the Paraná river. Here the river's current, which in the vicinity of the Iguazu river ran for six miles, would take him to Tacurú-Pucú in under five hours. With somber energy the man was able to reach the middle of the river. Yet here his benumbed hands dropped the paddle into the canoe, and he vomited yet again – this time, blood – then directed his gaze to the sun disappearing behind the mountain.

His whole leg, halfway to his thigh, was a hardened and deformed block bursting through his clothes. The man cut off the ligature and opened up the pants with his knife: his lower abdomen was incredibly painful, bloated with large livid marks. The man now believed he would never make it to Tacurú-Pucú by himself. So he decided to ask his friend Alves for help, even if a falling out had kept them apart for a long while.

The river's current now carried him to the Brazilian coast; the man was able to dock the canoe with ease. He dragged himself up the slope, but after twenty meters he lay there stretched out on his stomach, exhausted.

"Alves!" he cried with whatever force he could muster; but for a response he listened in vain.

"My dear Alves! Do not deny me this favor!" he screamed again, lifting his head from the ground. In the silence of the forest not a single murmur could be heard. The man still had the fortitude to return to his canoe, and the current, catching him once more, quickly carried him adrift.

Here the Paraná ran deep into an enormous river basin whose walls, higher than a hundred meters, gloomily canalized the river. The black woods ascended from the shores lined with blocks of basalt, which were also black. Behind there, on the sides, lay the eternal lugubrious wall at whose bottom the eddied river hastened into the incessant bubbling of murky waters. So aggressive was this landscape, where reigned but the silence of death. Nevertheless at dusk, its somber beauty and calm assumed a unique majesty.

The sun had already set when the man, half-prone at the bottom of the boat, experienced violent shivers. Then all of a sudden, to his astonishment, he sluggishly lifted up his head and straightened it. And he felt better. His leg hardly hurt any more; his thirst had diminished; and his breast, now free, opened up in slow inhalation.

The venom was beginning to leave his body, he had no doubts. He was almost alright, yet he still did not have the strength to move his hand, and reckoned that he would be fully recovered come the morning. He also calculated that he would be in Tacurú-Pucú in three hours.

His well-being increased and with it a somnolence replete with memories. He did not feel anything in either his leg or his stomach. Might his friend Gaona still be living in Tacurú-Pucú? Perhaps he could also see his former employer, Mr. Dougald, as well as the recipient of his work. Would he arrive soon? The sky, to the west, would now open up into a screen of gold, the river likewise having changed color. From the already-darkened Paraguayan coast the mountain let the twilght's freshness cascade over the river with emanations of orange blossoms and wild honey. Very high up, a pair of macaws silently crossed the sky in the direction of Paraguay.

Down here upon the river of gold the canoe was drifting rapidly, at times spinning around before a bubbling whirlpool. The man in that canoe kept feeling better and better, and in the meantime thought about the exact amount of time that had passed since he had last seen his former employer, Dougald. Had it been three years? Perhaps not, not that long. Two years and nine months? Perhaps. Eight and a half months? That's how long it had been, he was certain.

Suddenly he felt frozen up to his chest. What could this be? And yet his breathing ... He had made the acquaintance of Lorenzo Cubilla, the recipient of those wood products of Mr. Dougald's, in Puerto Esperanza one year on Good Friday. Was it a Friday? Yes, or was it a Thursday?

The man slowly stretched out his fingers.

"It was a Thursday ..."

And he stopped breathing.

Saturday, November 30, 2013 at 13:26

Saturday, November 30, 2013 at 13:26  I am by nature thus complete,

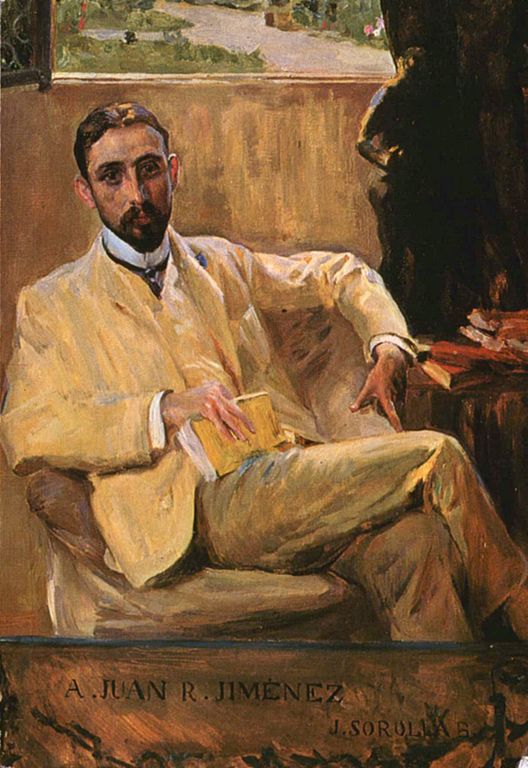

I am by nature thus complete,  Jiménez in

Jiménez in  Poems,

Poems,  Spanish literature and film,

Spanish literature and film,  Translation

Translation