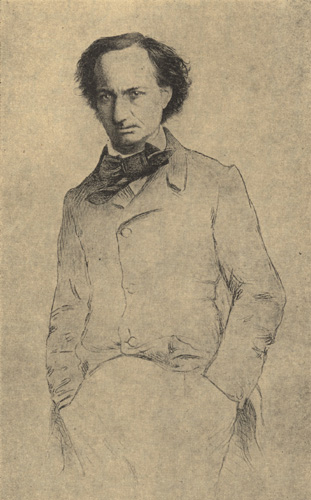

A prose poem ("The generous gambler") by this French poet, and source of a very famous quotation. You can read the original here.

Yesterday amidst the boardwalk crowd I felt myself grazed by a mysterious Being whom I recognized immediately and had always desired to meet, although I had never once laid eyes on him. He was doubtless of like desire, for in passing he gave me a suggestive wink which I hastened to obey. I followed him closely; and soon I descended behind him into a dazzling underground abode of a luxury none of Paris's finest houses could ever hope to approach. It was remarkable that I could have passed by this imposing lair so often without detecting its entrance. There reigned a carefully constructed, if intoxicating atmosphere which almost instantly erased all the tedious horrors of life; one's lungs filled with a somber beatitude akin to that which must afflict the lotus eater when, disembarking upon an enchanted isle beneath the rays of eternal afternoon, he feels born within them and, amidst the soporific sounds of melodious waterfalls, is then overcome by the desire never again to see his native shores, his wife, or his children, nor anew to scale the frothy crests of the sea.

Yesterday amidst the boardwalk crowd I felt myself grazed by a mysterious Being whom I recognized immediately and had always desired to meet, although I had never once laid eyes on him. He was doubtless of like desire, for in passing he gave me a suggestive wink which I hastened to obey. I followed him closely; and soon I descended behind him into a dazzling underground abode of a luxury none of Paris's finest houses could ever hope to approach. It was remarkable that I could have passed by this imposing lair so often without detecting its entrance. There reigned a carefully constructed, if intoxicating atmosphere which almost instantly erased all the tedious horrors of life; one's lungs filled with a somber beatitude akin to that which must afflict the lotus eater when, disembarking upon an enchanted isle beneath the rays of eternal afternoon, he feels born within them and, amidst the soporific sounds of melodious waterfalls, is then overcome by the desire never again to see his native shores, his wife, or his children, nor anew to scale the frothy crests of the sea.

There were unknown men's and women's faces of fatal beauty which I believed to have seen before in epochs or countries now impossible to recall with any exactness; faces which inspired within me not the fear ordinarily generated by a stranger's countenance, but rather a certain fraternal sympathy. Were I to attempt a description of the singular look in their eyes, I would insist on never having beheld gazes so energetically aglow with the horror, boredom, and immortal desire of feeling alive.

By the time we sat down my host and I had already become old and perfect friends. We ate; we drank immoderately of all sorts of extraordinary wines; and, no less extraordinarily, after several such hours I seemed no more drunk than he. Nevertheless, our wagers, that superhuman pleasure, had at various intervals interrupted our frequent libations; and I must admit that I gambled away my soul, owing in no small part to heroic insouciance and frivolity. Yet the soul being such an impalpable thing, so often useless and sometimes so annoying, I experienced in this loss only slightly less emotion than if I had misplaced, while out on a stroll, my business card.

For a long while we smoked several cigars whose incomparable flavor and aroma imbued my soul with a yearning for unknown shores and joys; inebriated on all these delights, and seizing a cup filled to the brim in a moment of excessive familiarity that did not seem to displeasure my host, I dared pronounce: "To your immortal health, Old Goat!"

We also spoke about the universe, about its creation and its future destruction; about the century's greatest idea, that is to say, about progress and perfectibility; and, in general about all the repositories of human infatuation. On this subject His Highness did not lack for light-hearted and irrefutable humor, expressing himself with a smoothness of diction and calmness of wit which I had never observed among all the world's most celebrated speakers. He explained to me the absurdity of various philosophies which had occupied human thought to the present day, and even deigned to entrust me with several fundamental principles whose benefits and propriety I was not to share with anyone. He never once bemoaned the poor reputation he enjoyed in every corner of the world; he assured me that he himself was the most interested of all in seeing superstition's demise, and that he had been fearful with regard to his own power on only one occasion. This was the day he had overheard a preacher, one more subtle than his colleagues, screaming from a pulpit: "When you hear praise, my brothers, of the progress brought by the Enlightenment, never forget that the Devil's greatest trick is convincing you that he doesn't exist!"

The recollection of that celebrated orator naturally led us to the subject of the academies, and my strange companion affirmed that it was hardly beneath him in many instances to breath life into a pedagogue's quill or speech, or even his conscience, and that he was almost always in attendance, if invisible, at all academy sessions.

Encouraged by such unstinting revelation, I asked him about God and whether he had recently seen Him. With an insouciance tinged with a certain sadness, he responded: "We greet one another whenever we meet, but in the fashion of two old gentlemen in whom innate politeness could never fully extinguish the memory of ancient grudges."

It was doubtful that His Highness had ever given such a lengthy audience to a mere mortal, and I was afraid to abuse my privileges. Finally, just as quivering dawn was whitening the panes, this celebrated character, sung by so many poets and served by so many philosophers unknowingly laboring towards his glory, said to me: "I want you to remember me fondly; and, as someone to whom people impute so much ill, I also wish to prove to you that I am at times – if I may borrow a vernacular expression – a good devil. In order to compensate the irreparable loss you have made of your soul, I will give you anyway what you would have won if your lot had been favorable, that is to say, the possibility of alleviating and defeating, for as long as you live, this bizarre feeling of boredom which is the source of all of humanity's maladies and miserable progress. There will be no desire formed in your heart that I won't help you attain; you will reign over your peers; you will be covered in praise and even in adoration; money, gold, diamonds, and enchanting palaces will seek you out and implore you to accept them, without your having made the slightest effort towards their obtainment. You will shift country and region as often as your imagination bids you to do so; you will be drunk indefatigably on sensual pleasures in charming locales where it is always warm and women smell as fragrant as flowers, and so forth and so on," he added as he rose and, with a pleasant smile, dispatched me thence.

Had I not been afraid of humiliating myself before such a large gathering, I would have willingly grovelled at the feet of this generous gambler in gratitude for his unprecedented munificence. After having taken my leave, however, incurable defiance little by little returned to my heart; I could scarcely believe in such prodigious fortune. And so, as I went to bed, praying out of imbecile habit, I repeated, half-asleep: "My God! O Lord! Have the Devil keep his word to me!"

Thursday, December 19, 2013 at 13:49

Thursday, December 19, 2013 at 13:49  As wintry day grows dim, as calm shades touch

As wintry day grows dim, as calm shades touch