Terror's Advocate

Monday, November 22, 2010 at 16:01

Monday, November 22, 2010 at 16:01 While your ancestors were eating acorns in the forest, mine were building palaces.

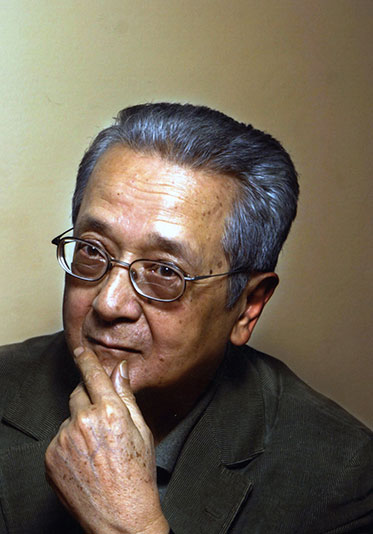

You may initially be rather appalled at the controversial subject of this documentary, born to a Vietnamese mother and a father hailing from this region of France, the first place in the world to use the Euro, and you may end your viewing no more sympathetic to his causes. Yet he couldn’t care less. The agenda that makes Vergès get up in the morning is the freedom of anticolonialist fighters and political radicals who, in his estimation, have not been given a fair shake. As an attorney of some of the more notorious political criminals in recent memory, his record continues unblemished. “I have had clients, friends, who were sentenced to death. Several dozen. Not one of them was executed.”

Vergès’s subsequent tears are hardly reptilian: he often believes in those people he chooses to defend even more strongly than they do in themselves (he even married one of them). As a twin, a half-Asian, a converted Muslim, a former soldier, a staunch anticolonialist, and an intellectual all in one busy and enigmatic person, Vergès’s mission in life is to support the unsupportable and defend the indefensible. The consequences of his actions are, however, well beyond what his vacillating ideals might imagine.

Vergès’s subsequent tears are hardly reptilian: he often believes in those people he chooses to defend even more strongly than they do in themselves (he even married one of them). As a twin, a half-Asian, a converted Muslim, a former soldier, a staunch anticolonialist, and an intellectual all in one busy and enigmatic person, Vergès’s mission in life is to support the unsupportable and defend the indefensible. The consequences of his actions are, however, well beyond what his vacillating ideals might imagine.

Although ostensibly a documentary, Terror’s Advocate is nothing like the biopics to which we have grown accustomed. We meet people from Vergès’s past and present who praise him, often anecdotally, but cannot agree on who or what he is. That his ethnicity, place of birth, and physical distance growing up away from Europe made him favor the politically disenfranchised is obvious. His compassion, while present, ebbs and flows in limited quantities; to him, the essence is the principle of the matter. The right to self-determination, a right that we are coming to understand as vital (albeit under the aphoristic caveat of giving someone a rope and letting him fashion his own particular knot), is what each person and nation state wants. In this way, Vergès is hopelessly modern, in love with the concept of defending those whom others detest and provoking those upon whom society can do nothing but smile. One of his alleged contributions to legal proceedings, for example, rejects the entire system as a sham and the terms used as relative to the oppressor and oppressed. Upon the independence of this country on July 3, 1962, Verges founded a publication that inspired the last novel of a well-known American writer. As his list of headline-making clients continues, Vergès becomes more steeped in the ways of the world, choosing his parties with an attenuated plan at hand. Now especially involved in Middle Eastern and African affairs, he also becomes a moving target for the Israeli secret service. And then, on the eve of expensive attempts to free this leader, he vanishes completely for eight years.

What he does in those years apart from write a book called Agenda (Simoen, Paris, 1978, although hardly mentioned online) is left open to debate. Some of his acquaintances claim to have spotted him in Paris, and finally he admits that he did spend some time in his adopted hometown. But he was also traveling to some of the farthest reaches of Asia, from which he finally returned in 1978, “thin, tanned, with a hardened expression,” as well as utterly penniless. Has he been in touch with his wife and children? A French journalist compares his Algerian wife, the Pasionaria of the FLN, to this member of the Résistance, who in no small irony is believed to have been murdered by Vergès’s most infamous client. Surely, it is suggested, a woman of such strength would not tolerate such negligence. So Vergès starts again, now mostly bereft of his political leanings, empathizing with the perpetrators of another violent attack in Paris itself.

And this is where, about halfway through, the film changes from biography to newsreel, and where we become painfully aware of the worldwide interconnections among revolutionary cells which have abandoned their political principles for power and gain. Suddenly it is no longer about Jacques, but about the house he built. The knowledge that a powerful French intellectual would succor their cause did not lead terrorists to do anything they wouldn’t have done alone, but it did tell them that, on one front at least, they were winning. The world was scared of their crimes, scared for its children, scared for a future of random violence against civilians designed to show how effete and indifferent their governments really were. Is that the goal of insurrectionists? Wasn’t it once the last resort of oppressed peoples to rage against their overlords? But violent, politically-driven nonconformity is as sellable and hollow as the material inequalities it despises. Just don’t tell Jacques Vergès.

*Note: Jacques Vergès died on August 15, 2013, at the age of 88, in Paris.

Reader Comments (2)

"Wasn’t it once the last resort of oppressed peoples to rage against their overlords? But violent, politically−driven nonconformity is as sellable and hollow as the material inequalities it despises."

You are more generous and compassionate, but your incisive, razor-edged intellect brings to mind another:

***

--Come up, Kinch! Come up, you fearful jesuit!

...

--Will he come? The jejune jesuit!

...

--God, isn't he dreadful? he said frankly. A ponderous Saxon. He thinks you're not a gentleman. God, these bloody English! Bursting with money and indigestion. Because he comes from Oxford. You know, Dedalus, you have the real Oxford manner. He can't make you out. O, my name for you is the best: Kinch, the knifeblade.

Able was I ere I saw ... whatever he saw those lost years. What does one do with eight years off? The change in his demeanor and principles upon returning from his exile, regardless of what he says to the contrary, is remarkable.