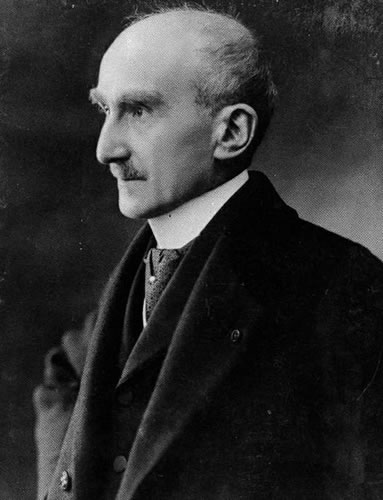

Bergson, "False problems"

Sunday, July 24, 2016 at 11:33

Sunday, July 24, 2016 at 11:33 An essay ("Les faux problèmes") by this French philosopher. You can read the original as part of this collection.

Now let us close this overly long parenthesis, which we had to open to show to what degree conceptual thought has to be reformed and sometimes even discarded to be able to arrive at a more intuitive philosophical approach. We said that this philosophy will most often turn away from the social vision of the object already created; instead, it will ask us to participate mentally in the act of creation. It will place us, therefore, on this particular spot, in the direction of the divine. As it were, it is quite human that the labor of individual thought would accept its insertion into social thought and use preexisting ideas like any other tool furnished by the community. Yet there is already something quasi-divine in the effort, however humble, of a mind who reinserts itself into the life force which generates societies that generate ideas.

This effort will exorcize certain ghosts of problems which have plagued the metaphysicist, that is to say, each one of us. I am talking about those alarming and insoluble problems which have more to do with that which is not than with that which is. Such is the problem of the origin of being: "How can it be that something – material, mind, God – exists? There must have been a cause, and a cause of a cause, and so on indefinitely." And so we continue from cause to cause; and if we stop it is not because our reason does not look beyond, but rather because our imagination closes its eyes, as if above an abyss, to escape the vertigo. And so persists the problem of order in general: "Why should there be an ordered reality in which our thought is recovered as if in a mirror? Why isn't the world incoherent?" I say that these problems refer to that which is not more than with that which is. We would never be surprised, as it were, that something exists – material, mind, God – if we did not implicitly admit that it would be possible for nothing to exist. We figure – or better, we think we figure – that being came to fill a void and that nothingness logically preceded being: primordial reality – what we call material, mind, or God – would then add itself to this, a scenario which remains incomprehensible. Similarly, we would never ask why order exists if we did not think we had conceived of a disorder which would submit to reality and which, consequently, would precede it, at least ideally. Thus order would need to be explained, whereas disorder rightly would not require explanation.

This effort will exorcize certain ghosts of problems which have plagued the metaphysicist, that is to say, each one of us. I am talking about those alarming and insoluble problems which have more to do with that which is not than with that which is. Such is the problem of the origin of being: "How can it be that something – material, mind, God – exists? There must have been a cause, and a cause of a cause, and so on indefinitely." And so we continue from cause to cause; and if we stop it is not because our reason does not look beyond, but rather because our imagination closes its eyes, as if above an abyss, to escape the vertigo. And so persists the problem of order in general: "Why should there be an ordered reality in which our thought is recovered as if in a mirror? Why isn't the world incoherent?" I say that these problems refer to that which is not more than with that which is. We would never be surprised, as it were, that something exists – material, mind, God – if we did not implicitly admit that it would be possible for nothing to exist. We figure – or better, we think we figure – that being came to fill a void and that nothingness logically preceded being: primordial reality – what we call material, mind, or God – would then add itself to this, a scenario which remains incomprehensible. Similarly, we would never ask why order exists if we did not think we had conceived of a disorder which would submit to reality and which, consequently, would precede it, at least ideally. Thus order would need to be explained, whereas disorder rightly would not require explanation.

This is the point of view that we risk taking as long as we only seek to understand. But let us try additionally to create (apparently, we can only do that through thought). When we dilate our will which we tend to reabsorb into our thoughts and sympathize more with the creative effort, these incredible problems retreat, diminish, and disappear. And that is because we sense that divinely creative willpower or thought is too rich and full, in its immensity of reality, for the idea of an absence of order or an absence of being to be able only to graze it. Representing the possibility of absolute disorder, and even more so of nothingness, would mean saying that it could not be the being of everything, and that would be a weakness incompatible with its nature, which is force. The more we consider the matter, the more abnormal and morbid seem the doubts which torment a normal and sane man. Let us recall the doubter that closes his window then returns to verify the closing, then verifies the verification, and so forth. If we were to ask him his reasons, he would reply that he could have reopened the window each time he tried as best he could to close it. And if he is a philosopher, he would intellectually transpose the hesitation in his behavior into this formulation of the problem: "How can one be sure, definitely sure, that one has done what one wanted to do?" But the truth is that his power to act is wronged, and here is where he suffers: he only had a semi-desire to carry out the act and that is why the act leaves him with nothing more than semi-certainty. Now can we solve the problem this man has given himself? Apparently not, but we will not give him such a problem: herein lies our superiority. At first glance, I would be able to believe that there is more in him than in me because both of us close the window, yet it is only he who raises a philosophical question. But the question with which he tasks himself is in reality nothing more than a negative; it is not more, but less; it is a deficit of willpower. This is precisely the effect that certain "big problems" have upon us when we place ourselves in the context of creative thought. They tend towards zero as we approach this context, being nothing more than the distance between the context and ourselves. And so we discover the illusion of the person who thinks he is doing more by tasking himself with such questions than by not tasking himself. It is very much like imagining that there is more in a half-consumed bottle than in a full bottle because the latter only contains wine, whereas the former contains both wine and emptiness.

But as soon as we intuitively perceive the truth, our reason resurfaces, corrects itself, and intellectually formulates its mistake. It has received the suggestion; it provides the check. Just like the diver on the ocean floor will feel and touch the wreck pointed out to him by the pilot high up the air, so will our reason immersed in the conceptual environment verify from point to point, through contact, analytically, what had been the object of a synthetic and supraintellectual vision. Without any warning from outside, the thought of a possible illusion would not have even grazed it because the illusion made up part of its nature. Shaken from its sleep, it will analyze the ideas of disorder, of nothingness and its congenerics. And it will recognize – if only for a moment, as the illusion will then immediately appear dispelled – that we cannot suppress an arrangement without another arrangement's taking its place, or replace one material without the substitution of another. Therefore "disorder" and "nothingness" really denote a presence – the presence of a thing or an order that does not interest us, which disappoints our effort or our attention. And it is our disappointment that is expressed when we call this presence an absence. In such a case, talking about the absence of all order and of all things – that is to say, of absolute disorder and absolute nothingness – would mean saying words devoid of sense, flatus vocis, since a suppression is simply a substitution envisaged on one of two sides, and the abolition of all order or of all things is a substitution of one side, the idea that has as much existence as that of a round square. So when the philosopher speaks of chaos and nothingness, he is doing nothing more than moving into the order of speculation – taken to the absolute and emptied there of all sense, of all effective content – two ideas made for practice which would then refer to a determined type of material or order, but not to all order and not to all material. From this point of view, what is to become of the two problems of the origin of order and the origin of being? They vanish; they vanish because they are only asked if we imagine being and order as "occurring," and consequently if we imagine nothingness and disorder as possible or at least conceivable. As it were, they are nothing more than words, a mirage of ideas.

May reason be penetrated by this conviction and be delivered from this obsession – only then will human thought breathe. It will no longer task itself with questions which retard its further progress.* It witnesses these difficulties vanish one by one, such as, for example, ancient Skepticism and modern criticism. It may also arrive at the side of Kantian philosophy and the "theories of knowledge" which emanate from Kantianism – and it doesn't stop there. As such, the very aim of The Critique of Pure Reason is to explain how a defined order can add itself to materials that are allegedly incoherent. And we know the price that we would pay for such an explanation: the human mind would impose its form on a "sensitive diversity" emanating from who knows where; the order which we find in things would be that which we ourselves impose. As a result, science would be legitimate but relative to our ability to know, and metaphysics would be impossible because there would be no knowledge beyond that of science. In this way, the human mind would be relegated to a corner like a schoolchild told to stand in the corner in punishment, prohibited from turning his head to see reality in the way it really exists. And there's nothing more natural if we have not noticed that the idea of absolute disorder is contradictory or, better, non-existent, a simple word by which we designate an oscillation of mind between two different orders. From this point of view, it is absurd to suppose that disorder logically or chronologically precedes order. The merit of Kantianism is to have developed this idea in all its consequences and presented it in its most systematic form, that of a natural illusion. But it has conserved it: Kantianism is in fact based upon this concept. Shed this illusion and we immediately bring back the human mind by science and metaphysics, by knowledge and by the absolute.

Thus we return to our starting point. We said that we needed to take philosophy to a higher level of precision, to place it in a position to resolve more specific problems, to make it an auxiliary and, if needed, a reformer of positive science. No more big system which embraces everything possible and sometimes also the impossible! Let us content ourselves with the real, material and mind. But let us also ask our theory to encompass the real so tightly that nothing, no other interpretation may slip between them. There will therefore be only one philosophy like there is only one science. Both will be created by means of a collective and progressive effort. And it is true that a perfection of the philosophical method will be imposed, symmetric and complementary to that which science once obtained.

------

* When we recommend a state of soul in which such problems vanish, let it be understood that we are only doing this to the problems which give us vertigo because they put us in the presence of the void. The quasi-animalistic condition of a being who never asks himself a single question is another matter, as is the semi-divine state of a mind who is not tempted to evoke, by an effect of human infirmity, artificial problems. For this privileged way of thinking the problem is always at the point of arising but is always arrested, whereby what is properly intellectual is stopped by its intellectual equivalent which sparks its intuition. The illusion is neither analyzed nor dissipated because it is not declared; yet it would be if it were declared; and these two antagonistic possibilities which are of an intellectual order are cancelled intellectually for not leaving room for anything apart from an intuition of the real. In the two cases we have cited it is the analysis of the ideas of disorder and nothingness which provide the intellectual equivalent of the intellectualist illusion.

Bergson in

Bergson in  Essays,

Essays,  French literature and film,

French literature and film,  Translation

Translation