Bergson, "The possible and the real" (part 2)

Saturday, July 16, 2011 at 13:24

Saturday, July 16, 2011 at 13:24 The second part to an essay by this philosopher and man of letters. You can read the original as part of this collection.

Great metaphysical problems are, in my estimation, as a rule badly described: they either tend to resolve themselves once their wording has been rectified, or reveal themselves to be problems formulated on the basis of an illusion, problems that disappear once we closely scrutinize the terms of this formulation. In effect, they are born from what we shift or transpose in fabricating what we will call creation. Reality is global and indivisible growth, gradual invention, and duration: as such, one might compare it to an elastic balloon that dilates little by little, suddenly assuming here and there unexpected shapes. But our intelligence thinks of the origin and the evolution of all this as an arrangement and rearrangement of parts that would be doing nothing more than changing places. Therefore it could, in theory, anticipate any state of arrangement and assembly; by starting with a definite number of stable elements, one is implicitly furnishing oneself in advance with all possible combinations.

Great metaphysical problems are, in my estimation, as a rule badly described: they either tend to resolve themselves once their wording has been rectified, or reveal themselves to be problems formulated on the basis of an illusion, problems that disappear once we closely scrutinize the terms of this formulation. In effect, they are born from what we shift or transpose in fabricating what we will call creation. Reality is global and indivisible growth, gradual invention, and duration: as such, one might compare it to an elastic balloon that dilates little by little, suddenly assuming here and there unexpected shapes. But our intelligence thinks of the origin and the evolution of all this as an arrangement and rearrangement of parts that would be doing nothing more than changing places. Therefore it could, in theory, anticipate any state of arrangement and assembly; by starting with a definite number of stable elements, one is implicitly furnishing oneself in advance with all possible combinations.

That is not all. Reality, such as we perceive it directly, is of a fullness that never ceases to swell, one that knows no void or emptiness. It has extension as it has duration; yet this concrete stretch is never infinite space and infinitely divisible so that intelligence exists as a terrain on which to build. Concrete space has been extracted from things. These things are not in it, it is concrete space that is in these things, and as soon as our thought process rationalizes reality, it makes space into a receptacle. As it is accustomed to assembling parts in a relative void, it may think that reality encompasses who-knows-what kind of absolute void. For if ignorance of radical novelty is at the origin of metaphysical problems poorly described, the habit of moving from void to fullness is the source of non-existent problems. Besides, it is easy to see that the second error is already implicated in the first. But I would first like to define the error more precisely.

I say that there are pseudo-problems, and that these are the most worrisome problems of metaphysics. I will divide them in two categories: the first category has engendered theories of being; the second category theories of knowledge.

The first category consists of asking oneself why there is being, why something or someone exists. The nature of this is of little importance. Regardless of whether it is matter, mind, or one and the other, or that both matter and mind are not enough, demonstrating a transcendent Cause, when one has considered existences and causes, and causes of these causes, one feels oneself drawn into a course of infinite length. If one stops, it is simply to save oneself from the dizziness. We may still say, or think we may still say, that the difficulty remains, that the problem remains and will never be resolved. It will, in fact, never be resolved. But it also never ought to be brought up.

It is only brought up if we imagine a certain nothingness that would precede being. One says to oneself: "there might be nothing there," and one may be surprised when, in fact, there is something there after all – or Someone. But analyze this phrase once more: "there might be nothing there." You will see that you are dealing with words, and not at all with ideas, and that "nothing" has no meaning here. "Nothing" is a term of habitual language that can only make sense if we remain on the terrain, belonging to man, of action and fabrication. "Nothing" means the absence of what we seek, of what we desire, of what we await. Indeed, to suppose that experience could never present us with an absolute void means that it would be limited, that it would have contours, that it would be, after all, something. But in reality there is no void. We only perceive and, as it were, only conceive of fullness. A thing only disappears when it has been replaced by something else. Thus suppression also means substitution, only that we say "suppression" when we foresee the substitution of only one of two halves, or rather one of two faces – the face that interests us.

We confirm in this way that we would like to direct our attention to the object that has left, and to turn our attention away from the object which has replaced it. So we say that there is nothing more, understanding by that statement 'that which does not interest us,' and that we are interested in 'that which is no longer there' or 'that which could have been there.' The idea of absence, or nothingness, or nothing, is thus inseparably linked to that of suppression, real or potential, and the idea of suppression is, in turn, nothing more than an aspect of the idea of substitution. And it is here that we find methods of thinking which we employ in our daily lives. It is of particular interest to our industry that our thinking knows how to linger upon reality and, when necessary, remain attached to what was and what could be, instead of being monopolized by what is. But when we betake ourselves from the domain of fabrication to that of creation, when we wonder why there is being, why there is something or someone, why the world or God exists and why there is not nothing, when we wrestle with the most worrisome of metaphysical problems, we accept virtually an absurdity because all suppression is a substitution. And if the idea of a suppression is nothing more than the truncated idea of a substitution, then talking at all about suppression is simply summoning a substitution, which would contradict itself if it were not one.

For the whole idea of suppression has precisely enough existence as that of a round square – the existence of a sound, flatus vocis – or if it does in fact represent something, it translates a movement of the intelligence which goes from one object to another, preferring that which it has just left to that before which it finds itself, and, in so doing, designates the presence of the second by the 'absence of the first.' We considered the whole matter then made it disappear piece by piece, one after the other, without consenting to see what replaced it. It is therefore the totality of these presences, simply aligned in a new order, that one finds before one's eyes when one wishes to sum up the absences. In other words, this pretended representation of an absolute void is, in reality, that of a universal fullness in a mind that leaps indefinitely from part to part, having resolved never to consider the void of its dissatisfaction rather than the fullness of things. Which brings us back to saying that the idea of Nothing, when it is not just a simple word, implies as much matter as that of Everything, with, what is more, an operation of thought.

I would say the same for the idea of disorder. Why is the universe ordered? How does a rule impose itself upon the irregular, how does form impose itself upon matter? How is it that our thinking finds itself among these things? This problem, which has become for modern thinkers the problem of knowledge after having been, for ancient thinkers, the problem of being, is born from an illusion of the same kind. It disappears once one considers that the idea of disorder has a definite sense in the domain of human industry or, as we say, in fabrication, but not in the domain of creation. Disorder is simply the order we do not seek. You cannot suppress one order, even by thought, without having another rise to the surface. If there is no aim or willfulness, there is simply a mechanism; if the mechanism yields, it is to the benefit of willfulness, of capriciousness, of an aim. But when you expect one of these two orders and you find the other, you say that there is disorder, formulating what is in terms of what could or should be, and objectifying your regret. Thus all disorder is composed of two things: outside of us, an order; and within us, the representation of a different order which is the only one that interests us. Suppression therefore again means substitution. And the idea of the suppression of all orders, that is to say, the idea of absolute disorder, contains a true contradiction, because it involves assigning one face to an operation that, hypothetically, consists of two. One may also say that the idea of absolute disorder only represents a combination of sounds, flatus vocis, or, if this idea responds to something, it translates a movement of the mind that leaps from mechanism to aim, from aim to mechanism, and which, to mark the spot where it is, prefers to indicate each time the place where it is not. Thus, in wanting to suppress order, you provide yourself with two or more orders. Which brings us back to saying that the conception of an order being added on to an "absence of order" implies an absurdity and thus the problem disappears.

The two illusions which I have just mentioned really compose only one. They involve believing that there is less in the idea of a void than in the idea of fullness, less in the concept of disorder than in that of order. In reality, there is more intellectual content in the ideas of disorder and nothing, when they represent something, than in the ideas of order and existence when they imply many orders, many existences and, moreover, a trick of the mind which juggles them unconsciously.

And so, I find the same illusion in the case that concerns us. At the heart of these doctrines that do not recognize the radical novelty of every moment of evolution there are misunderstandings, even errors. But most of all there is the idea that the possible is less than the real, and that, for that reason, that the possibility of things precedes their existence. They would thus be representable in advance; one could think of them before they were actually realized. But it is the inverse that is the truth. If we leave aside for the moment closed systems subject to purely mathematical laws, isolable because they are not gnawed upon by duration, if we consider the ensemble of concrete reality or very simply the world of life, and with even more reason the world of our consciousness, we find that there is more, and not less, in the possibility of each of these successive states than in their reality. For the possible is merely the real with, in addition, an act of the mind which propels therefrom the image into the past the moment it is produced. But this is what our intellectual habits prevent us from perceiving.

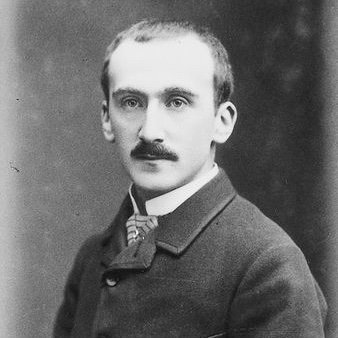

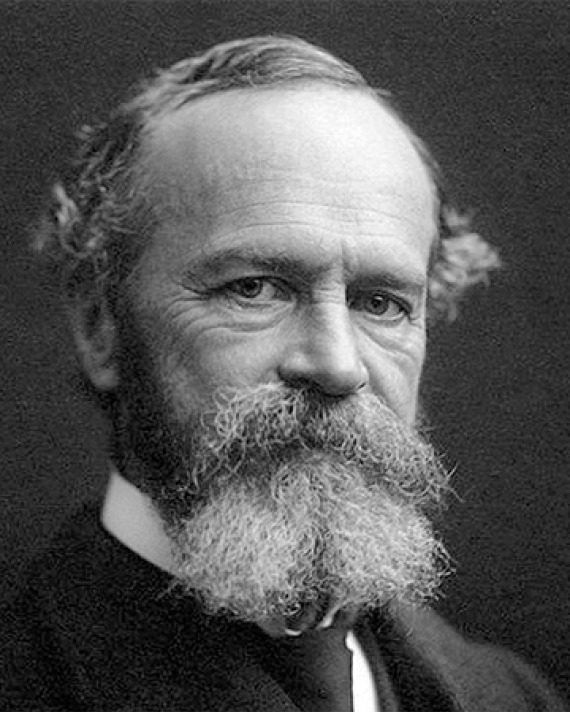

Bergson in

Bergson in  Essays,

Essays,  French literature and film,

French literature and film,  Translation

Translation