The Untouchable

Friday, November 11, 2016 at 13:23

Friday, November 11, 2016 at 13:23 I wanted to tell her about the blade of sunlight cleaving the velvet shadows of the public urinal that post-war spring afternoon in Regensburg, of the incongruous gaiety of the rain shower that fell the day of my father's funeral, of that last night with Boy when I saw the red ship under Blackfriars Bridge and conceived of the tragic significance of my life; in other words, the real things; the true things.

Why do so many betray all that they love? An expert or three will aver that these traitors are ashamed of what they love, ashamed either of humble roots or past generations, or simply and unavoidably attracted to the garish limelight (which soon will resemble the pale moonlight, but anyway). There are other reasons, of course, reasons that involve one's own identity, so quietly and carefully folded up in a hidden suitcase, a suitcase that one cannot help but look at every time one enters the room. A suitcase one begins to imagine, as one begins to imagine entering the room and finding it again and again to make sure it's still there intact, undiscovered, sealed from oxygen and mankind. It is then, we may suppose, that the dreams commence. The nightmares or day-mares about walking in one dire day and not finding a suitcase anywhere. Because the suitcase was never there; nothing was ever hidden; and one's past comes crashing into one's present like two mirrored doors in close collision. A summary of the life and fate of the narrator of this novel.

Why do so many betray all that they love? An expert or three will aver that these traitors are ashamed of what they love, ashamed either of humble roots or past generations, or simply and unavoidably attracted to the garish limelight (which soon will resemble the pale moonlight, but anyway). There are other reasons, of course, reasons that involve one's own identity, so quietly and carefully folded up in a hidden suitcase, a suitcase that one cannot help but look at every time one enters the room. A suitcase one begins to imagine, as one begins to imagine entering the room and finding it again and again to make sure it's still there intact, undiscovered, sealed from oxygen and mankind. It is then, we may suppose, that the dreams commence. The nightmares or day-mares about walking in one dire day and not finding a suitcase anywhere. Because the suitcase was never there; nothing was ever hidden; and one's past comes crashing into one's present like two mirrored doors in close collision. A summary of the life and fate of the narrator of this novel.

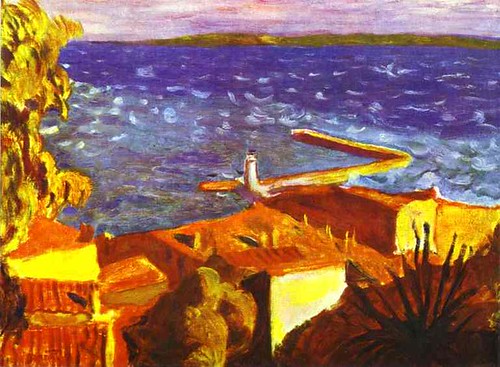

That our man is called Victor Maskell should not influence our impression: he has lost and will continue to lose, and the masks he has chosen are facsimiles of his own countenance. As we begin our tale, Maskell has been outed as having been far less patriotic than he might have seemed in the preceding decades establishing himself as one of Britain's finest Baroque experts, in particular of this painter of genius. Now at the threshold of his eighth decade on an ungrateful earth, he has become a widower, a lover of his "own kind," and an occasional parent, his son loathing him for what he was, his daughter pitying him for what he wasn't. He has long pondered the nature of his quandary:

In the spy's world, as in dreams, the terrain is always uncertain. You put your foot on what looks like solid ground and it gives way under you and you go into a kind of free fall, turning slowly tail up and clutching on to things that are themselves falling. This instability, this myriadness that the world takes on, is both the attraction and the terror of being a spy. Attraction, because in the midst of such uncertainty you are never required to be yourself; whatever you do, there is another, alternative you standing invisibly to one side, observing, evaluating, remembering. This is the secret power of the spy, different from the power that orders armies into battle; it is purely personal; it is the power to be and not to be, to detach oneself from oneself, to be oneself and at the same time another. The trouble is, if I were always two versions of myself, so all others must be similarly twinned with themselves in this awful, slippery way.

And where did Maskell split his being, dividing the poor son of an Irish preacher from the soon-to-be Soviet informer ("the fact is, I was both a Marxist and a Royalist")? Cambridge University of the 1920s and 1930s, a hotbed of radical thought and, on occasion, even radical action. The Great War has led to a peace once unimaginable, and the fervent idealism that courses through the veins of able-bodied intellectuals when serenity and prosperity have been secured has now embraced a new approach to humanity: a destruction of greed. The atmosphere in those years, says Maskell, "had something thrillingly suppressed in it, as if at any moment the most amazing events might suddenly begin to happen." And what events might he mean? Oh, the downfall of capitalism, the founding of a worker-based government which would control the means of production – and I believe we don't need to go on. Himself a distant relative of the queen, Maskell was not alone in his endeavors: there is Boy, who splits his day evenly between cottaging and stealing state secrets; Nick, a rich, ambitious, and rather sleek operator, whose sister Maskell would eventually marry, even if it is her brother he more greatly desired; and Leo Rothenstein, who buys Maskell his first Poussin, although maybe not for the reasons supplied at the time of purchase. There were others, of course; but their roles were mostly as supporting actors, which is another way of saying they were granted brief spurts of magniloquence then killed for the cause. One exception to this rule is the man known as Querell.

Querell is a spy alright, but unlike his confederates he is also a writer of a series of potboilers ("He was genuinely curious about people – the sure mark of the second-rate novelist"). Maskell wonders and wonders some more about Querell, who does not seem to eat or sleep or do anything except lurk, smoking "the same, everlasting cigarette, for I never seemed able to catch him in the act of lighting up." A rather revolting scene early on in the novel, coupled with his professed Catholic faith, make Querell an even more unlikely human being and a much more likely Frankenstein's monster. So when someone informs Maskell, that "that Querell now, he has the measure of us all," our art historian begins to reconsider the popular novelist:

Querell would come round, tall, thin, sardonic, standing with his back against the wall and smoking a cigarette, somehow crooked, like the villain in a cautionary tale, one eyebrow arched and the corners of his mouth turned down, and a hand in the pocket of his tightly buttoned jacket that I always thought could be holding a gun .... You would glance at the spot where he had been standing and find him gone, and seem to see a shadowy after-image of him, like the paler shadow left on a wall when a picture is removed.

If Querell is meant to represent, as some have surmised, this writer, then this is cruelty indeed. And it should not detract from our enjoyment of The Untouchable that Victor Maskell is modeled, hewn, and traced on this infamous figure (with the name a punning reference to this scholar), nor that many other characters, most notably Boy, have historical archetypes. Blunt was a spy, an art historian, a Communist, and a homosexual, basically in that order, and the proud Briton will always shudder at the mention of his name. Maskell knows very little about the cause he supposedly serves, probably because, for a spy, he is a very poor judge of man. An orphaned chapter segment prattles on about this anarchist, the idol of many a collegiate ignoramus, a quickly-abandoned tactic which, while oddly out of line with the narrative, spares us the stale biscuit aphorisms of the hidebound comrade. The passage is fake just like Marxism is fake, the lazy imposition of an artificial understanding on a world far more natural and complicated than even the most perspicacious Marxist could ever suspect. The only thing we are convinced of is Victor Maskell's utter selfishness, which he admits, his flimsy homosexuality (which, for most of the novel, he experiences vicariously through Boy), his family feelings (which he barely senses), and that the only thing he truly seeks is to imbue his life with some profundity, to be as memorable as the Poussin masterpieces he knows he can merely admire but never replicate.

As in all of Banville, passages of extreme beauty grace page after page ("The Daimler .... vast, sleek, and intent, like a wild beast that had blundered into captivity and could only be let out, coughing and growling, on occasions of rare significance"; "We sat opposite each other ... in a polite, unexpectedly easy, almost companionable silence, like two voyagers sharing a cocktail before joining the captain's table, knowing we had a whole ocean of time before us in which to get acquainted"; "You will find my people at the top, or if not at the top, then determinedly scaling the rigging, with cutlasses in their teeth"), but to his credit Maskell does not drift into unabashed sentimentality, even when he fully succumbs to his genetic programming. And who is the female interlocutor in the quote beginning this review? One Serena Vandeleur (whose name recalls characters in both this novel and this one), in principle a young journalist yearning for a breakthrough as the biographer of an outcast, although Maskell has his suspicions about her true agenda. As, it should be said, he comes to have about everyone's agenda; such are the wages of duplicity. Perhaps he could just take a group photograph of his backstabbing brethren for his biography and title it The Shepherds of Arkady.

Banville in

Banville in  Book reviews,

Book reviews,  English literature and film

English literature and film