The Sea

Tuesday, January 19, 2010 at 09:00

Tuesday, January 19, 2010 at 09:00 One should never trust a book by its publisher's blurb, never mind the ridiculous cover ultimately inflicted upon it by the brokers of style (occasionally, a first edition hardcover will be more to the writer's tastes, thereafter wigwammed into hideous shades of bland). Blurbs of course are even more egregious offenders. Yes, they are meant to sell, which means, I suppose, that they must provide tout pour tous without offending anyone too heartily. They must in a way resemble women's dresses: enough is left to the spectator to propel dark fantasies; enough is removed from conjecture to affirm its authenticity. I will spare you this book's blurb not because it is nonsensical, but simply because it is as vague as its title – pun fully intended – and neither title nor blurb nor first edition hardcover picture binds it with the thinnest strand of justice.

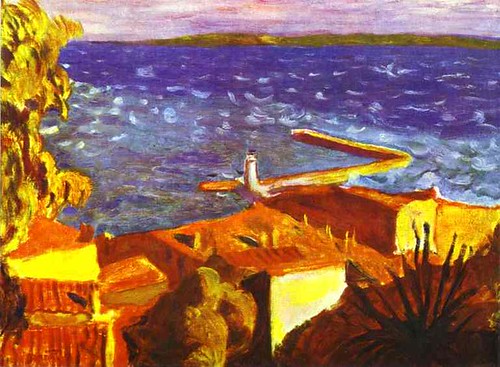

Our aging narrator is an art critic, a widower, an Irishman, and someone whose command of English ebbs and flows in soft, scummed pats on an endless beach. His name is Max Morden, and if he finds the name of his dying wife's treating physician, Dr. Todd, "a joke in bad taste on the part of polyglot fate," one would do well to consider his own. His obsession, apart from the past (famously stated to "beat inside [him] like a second heart"), is the meaning of all his time and space if his life were a series of pictures by his beloved Bonnard, or by some of the other, mostly post-Impressionist names he so casually drops. His quandary is what life has cost him, why he now awaits in agnostic gloom the withering of his Anna; why his daughter Claire, because of her sturdy and almost clomping awkwardness, will never marry; why he was born into one lowly station and never allowed to board a first-class train. His imagery will be dreams mixed with the past, or the present tinged with other hues, such as "those plangent autumn evenings streaked with late sunlight that seemed [themselves] a memory of what sometime in the far past had been the blaze of noon." The Sphinx's riddle this is not quite, but his steps and circuits do suggest a certain path:

Our aging narrator is an art critic, a widower, an Irishman, and someone whose command of English ebbs and flows in soft, scummed pats on an endless beach. His name is Max Morden, and if he finds the name of his dying wife's treating physician, Dr. Todd, "a joke in bad taste on the part of polyglot fate," one would do well to consider his own. His obsession, apart from the past (famously stated to "beat inside [him] like a second heart"), is the meaning of all his time and space if his life were a series of pictures by his beloved Bonnard, or by some of the other, mostly post-Impressionist names he so casually drops. His quandary is what life has cost him, why he now awaits in agnostic gloom the withering of his Anna; why his daughter Claire, because of her sturdy and almost clomping awkwardness, will never marry; why he was born into one lowly station and never allowed to board a first-class train. His imagery will be dreams mixed with the past, or the present tinged with other hues, such as "those plangent autumn evenings streaked with late sunlight that seemed [themselves] a memory of what sometime in the far past had been the blaze of noon." The Sphinx's riddle this is not quite, but his steps and circuits do suggest a certain path:

A dream it was that drew me here. In it, I was walking along a county road, that was all. It was in winter, at dusk, or else it was a strange sort of dimly radiant night, the sort of night that there is only in dreams, and a wet snow was falling. I was determinedly on my way somewhere, going home, it seemed, although I did not know what or where exactly home might be. There was open land to my right, flat and undistinguished with not a house or hovel in sight, and to my left a deep line of darkly louring trees bordering the road. The branches were not bare despite the season, and the thick, almost black leaves drooped in masses, laden with snow that had turned to soft, translucent ice. Something had broken down, a car, no, a bicycle, a boy's bicycle, for as well as being the age I am now I was a boy as well, a big awkward boy, yes, and on my way home, it must have been home, or somewhere that had been home, once, and that I would recognize again, when I got there. I had hours of walking to do but I did not mind that, for this was a journey of surpassing but inexplicable importance, one that I must make and was bound to complete.

Morden, like the narrator of this novel, is tall, almost disruptively large, and a proud dipsomaniac. He remains not so much drunk during the novel as hungover, gliding between the realm of wishful wanting to the dry sardonicism of resigned failure. His thirst seems quenchable only by an ocean, his tone vacillates but never falters, and his main interest will always be the four Graces and the sea.

The family Grace boasts the normal components of upper-middle class life, a stratum that eludes our poor Max. Max endures a childhood of parental bickering to become the itinerant teenage son of a single mother, arriving at each new lodging house "always it seemed on a drizzly Sunday evening in winter." It is then no surprise that he focuses his efforts on a childhood summer in the vicinity of four persons he is not quite sure ever existed: Carlos Grace, a grey-chested ruffian, Connie Grace, the thick and voluptuous mother, and their two children, the mute Myles and the waifish nymphet Chloe. A brief aside: I have always found Chloe an odd name to bestow upon a child, almost signifying in advance a weakness or vulnerability that could burst as easily as a jellyfish – but I digress. Chloe will become in time the vessel for Max's affection, although his first attraction is for the bulging and shapely Connie, both of whom have some affinity in name with Max's eventual wife and child. Once Anna is diagnosed and the hourglass flipped, Max returns to that same sea, if the sea can ever truly be said to be the same:

Throughout the autumn and winter of that twelvemonth of her slow dying we shut ourselves away in our house by the sea, just like Bonnard and his Marthe at Le Bosquet. The weather was mild, hardly weather at all, the seemingly unbreakable summer giving way imperceptibly to a year-end of misted-over stillness that might have been any season. Anna dreaded the coming of spring, all that unbearable bustle and clamour, she said, all that life. A deep, dreamy silence accumulated around us, soft and dense, like silt.

Early in our narrative, Morden agrees with this Russian poet – almost always a wise choice – about the incomparability of October upon the creative psyche, and yet he betrays Pushkin's testament with his obsessive revisiting of the poet's least favorite season, summer (I should add that that the second sentence of this passage is one of the finest in the English language). And there lingers another character amidst these Graces and the burgeoning historian, a nanny of sorts, a lithe, pale girl with the name of Rose. Rose has a cruel secret that cannot be rightly shared, and its late discovery relegates it to oblivion. No, whatever we may think of these band of merry players, it is our hero that demands attention, that shifts and jumps in unmeasured steps to the beat of the past beating within him, beating him because it has escaped and is immortal and he will fade into the ocean whence he and memory sprang in tandem. We also remember another Russian author's tortured recounting of a summer gained and lost to chance and, ultimately, to consumption, a summer from which poor Humbert never recovered. Count Morden among the eternally convalescent.

Banville in

Banville in  Book reviews,

Book reviews,  English literature and film

English literature and film

Reader Comments