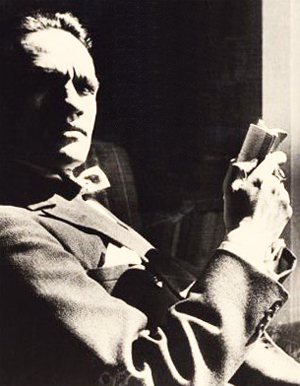

A story ("The Library of Babel") by this Argentine. You can read the original here.

The universe (what others call the Library) consists of an indefinite, perhaps even infinite number, of hexagonal galleries with vast ventilation shafts at the center surrounded by the lowest of handrails. From any of these hexagons the lower and upper floors can be seen – interminably. The distribution of the galleries is invariable. Twenty shelves, five long shelves to a side, cover all the sides save two; their height, which is that of the floors, barely exceeds that of a normal library shelf. One of its free sides gives onto a narrow corridor which disembogues into another gallery identical to the first and to them all. On the left and the right of the corridor there are two miniscule offices. One allows for sleep standing up; the other satisfies your calls of nature. Here passes the spiral staircase which sinks and rises towards the remote distance. In the corridor there is a mirror that faithfully duplicates appearances. Men tend to infer from this mirror that the Library is not infinite (and if it were really so, what would be the point of this illusory duplication?); I prefer to dream that the burnished surfaces shape and promise the infinite ... Light emanates from one of those spherical fruits which bear the name of light bulb. There are two in every hexagon – transverse. The light they emit is insufficient, incessant.

Like all the men of the Library, I traveled during my youth. I pilgrimaged in search of a book, perhaps a catalogue of catalogues; now that my eyes can almost no longer decipher what I write, I am preparing myself to die but a few leagues from the hexagon in which I was born. Dead, there will be no lack of pious hands that will carry me along the guardrail; my tomb shall be the unfathomable air; my body will plummet a long distance and disintegrate and dissolve in the wind engendered by the fall, a fall that is infinite. I affirm that the Library is interminable. Idealists argue that the hexagonal rooms are a necessary form of absolute space or, at least, of our intuition of space. They reason that a triangular or pentagonal room is inconceivable. (Mystics claim that mystic ecstasy reveals to them a circular room with a large book with a continual spine that is turned towards all the walls. But their testimony is suspicious, their words obscure: this circular book is God.) It is enough for me, for now, to repeat the classical report: The Library is a sphere whose exact center is some hexagon, whose circumference is inaccessible.

Like all the men of the Library, I traveled during my youth. I pilgrimaged in search of a book, perhaps a catalogue of catalogues; now that my eyes can almost no longer decipher what I write, I am preparing myself to die but a few leagues from the hexagon in which I was born. Dead, there will be no lack of pious hands that will carry me along the guardrail; my tomb shall be the unfathomable air; my body will plummet a long distance and disintegrate and dissolve in the wind engendered by the fall, a fall that is infinite. I affirm that the Library is interminable. Idealists argue that the hexagonal rooms are a necessary form of absolute space or, at least, of our intuition of space. They reason that a triangular or pentagonal room is inconceivable. (Mystics claim that mystic ecstasy reveals to them a circular room with a large book with a continual spine that is turned towards all the walls. But their testimony is suspicious, their words obscure: this circular book is God.) It is enough for me, for now, to repeat the classical report: The Library is a sphere whose exact center is some hexagon, whose circumference is inaccessible.

Five shelves correspond to each one of the walls of each hexagon; each shelf incorporates thirty-two books of the same format; each book has four hundred ten pages; each page has forty lines; each line has some eighty letters of black color. There are also letters on the back of every book; these letters neither indicate or prefigure what the pages will say. I know this disconnect sometimes seemed mysterious. Before I summarize the solution (whose discovery, despite its tragic projections, is perhaps the main chapter of the story) I would like to recur to certain axioms.

The first: the Library has existed ab aeterno – from the beginning of time. Of this truth, whose immediate corollary is the future eternity of the world, no reasonable mind could have any doubts. Man, that imperfect librarian, could be the work of chance or of malevolent demiurges; the universe with its elegant allocation of shelves, of enigmatic tomes, of indefatigable staircases for the traveler and latrines for the seated librarian, can only be the work of a god. To perceive the distance that persists between the divine and the human, it is sufficient to compare these rude tremulous symbols which my fallible hand scribbled on the cover of a book, with the organic letters of its inside: punctual, delicate, utterly black, inimitably symmetrical.

The second: the number of orthographic symbols is twenty-five.* This verification permitted, three hundred years ago, the formulation of a general theory of the Library and the satisfactory resolution of a problem which no conjecture had ever deciphered: the formless and chaotic naturalness of almost all the books. One, which my father saw in a hexagon of circuit fifteen ninety-four, consisted of the letters M C V perversely repeated from the first line to the last. Another (very often consulted in this zone) is a mere labyrinth of letters; but the ultimate page says Oh time, your pyramids. It is already known: for every reasonable line or honest piece of news there are leagues of senseless cacophonies, verbal farragoes and incoherencies. (I know of a wild, unbroken region whose librarians repudiate the superstitious and vain custom of searching for meaning in books and outfitted their library so that one might look in dreams or the chaotic lines of the hand ... They admit that the inventors of writing imitated the twenty-five natural symbols, but maintain that this application is by chance and the books have no meaning in and of themselves. This report, we will soon see, is not completely false ...)

For a long time it was believed that these impenetrable books corresponded to past or remote languages. It is true that more ancient men, those first librarians, employed a language quite different from that which we speak today; it is likewise true that a few miles to the right the language is dialectic and ninety floors up it is incomprehensible. All this, I repeat, is true; but four hundred and ten pages of unchanging M-C-Vs cannot correspond to any language, however dialectic or rudimentary it may be. Some insinuate that every letter was able to influence the subsequent letter, and that the value of M C V in the third line of page seventy-one was not a language which could sustain the same series on another position of the page, but this thesis did not prosper. Others thought of cryptography; this conjecture was universally accepted, although not in the sense in which it was formulated by its inventors.

Five hundred years ago the head of an upper hexagon** came upon a book as confused as the others, but which had almost two pages of homogenous lines. He showed his find to a roaming decipherer who told him that these lines were in Portuguese; others told him they were in Yiddish. Before a century had passed, the language had been established: a Samoyedic-Lithuanian dialect of Guaraní with inflections from classical Arabic. The contents were likewise deciphered: notions of combinatory analysis illustrated with examples of variations with unlimited repetition. These examples permitted a librarian of genius to discover the fundamental law of the Library. This thinker observed that all the books, however diverse they may be, consisted of the same elements: the space, the period, the comma, and the twenty-two letters of the alphabet. He then alleged a fact that all the travelers had confirmed: there did not exist, in the vast Library, two identical books. From these incontrovertible presumptions he deduced that the Library was whole and that its shelves recorded all the possible combinations of the twenty-odd orthographic symbols (a number that, although enormous, was not infinite) or perhaps everything which it was convenient to express – in every language. Everything: the meticulous and detailed history of the future; the autobiographies of the archangels; the faithful catalogue of the Library; thousands and thousands of false catalogues; the demonstration of the falsity of these catalogues; the demonstration of the falsity of the true catalogue; the Gnostic gospel of Basilides; the commentary on this gospel; the true account of your death; the version of every book in all the books; the treatise that Bede could have written (and did not write) on the mythology of the Saxons; the lost books of Tacitus.

When it was declared that the Library spanned all books, the first impression was of extravagant happiness. All men felt themselves masters of an intact and secret treasure. There was no personal or global problem whose eloquent solution did not exist – in some hexagon. The universe was justified; the universe brusquely usurped the unlimited dimensions of hope. At that time there was much talk about the Vindications: books of prophecy and apology, which forever vindicated the acts of every man in the universe and guarded the prodigious mysteries of his future. Thousands of covetous persons abandoned the sweet hexagon of their birth and sped up staircases, urged on by the vain proposition of encountering their Vindication. These pilgrims argued in the narrow hallways, cast obscure curses, strangled one another on the divine staircases, hurled deceptive books to the bottom of tunnels, and died from having been thrown off cliffs by men in remote regions. Others went mad ... The Vindications exist (I have seen two which refer to persons from the future, persons who are perhaps not imaginary); but the seekers did not remember that the possibility of a man encountering his own Vindication, or some perfidious variation of his own, is computable at zero.

Thus an explanation of the basic mysteries of the universe was also hoped for: the origin of the Library and of time. It is plausible that these solemn mysteries can be explained in words: if the language of the philosophers does not suffice, the multiform Library might have produced the unprecedented language required as well as the grammars and vocabularies of this language. The hexagons have fatigued men for four centuries ... There are official seekers, inquisitors. I have seen them in the fulfillment of their function: they always arrive exhausted; they speak of a staircase without steps that almost killed them; they speak of galleries and staircases with the librarian; occasionally they take up the nearest book and leaf through it in seach of infamous words. Visibly, no one expects to find anything.

Unbridled hope was followed, as is natural, by excessive depression. The certitude that one shelf in one hexagon contained precious books, and that these precious books were inaccessible, seemed almost unbearable. One blasphemous sect suggested that the searches should end and everyone should shuffle letters and symbols until they construct, through an improbable gift of chance, these canonical books. The authorities saw themselves obligated to promulgate strict orders. The sect disappeared, but in my childhood I saw old men hiding for long periods of time in the latrines, with metal discs in a prohibited beaker, feebly mimicking the divine disorder.

Others, inversely, believed it was paramount to eliminate the useless works. They invaded the hexagons, showed credentials that were not always false, leafed with annoyance through a volume and condemned whole shelves: to their hygienic and ascetic furor we owe the senseless loss of millions of books. Their name has been execrated, but some deplore the "treasures" which their frenzy destroyed, neglecting the notorious facts. One: the Library is so enormous that all reduction of human origin turns out to be infinitesimal. Another: every exemplar is unique, irreplaceable, but (as the Library is whole) there are always many hundreds of thousands of imperfect facsimiles: works that do not differ apart from a letter or comma. Contrary to public opinion, I dare to suppose that the consequences of the depredations committed by the Purifiers have been exaggerated by the horror that these fanatics provoked. They were spurred on by the delirium of conquering the books of the Crimson Hexagon: books of a lesser format than the natural books; omnipotent, illustrated and magical.

We also know of another superstition of that time: that of the Man of the Book. On some shelf of some hexagon (men reasoned) there ought to exist a book that may be the perfect cipher and compendium to all the rest: a certain librarian went through it and he has become analogous to a god. In the language of this zone there still persist vestiges of the cult of this remote functionary. Many have pilgrimaged in search of Him. For a century the most diverse routes were pursued in vain. How could one locate the venerated secret hexagon which accommodated the book? Someone proposed a regressive method: in order to locate book A, one would first need to consult book B which would indicate the site; in order to locate book B, one would first need to consult book C, and so forth for infinity ... It is to adventures like these that I have consecrated my years, with them now consumed. It does not seem implausible to me that on some shelf of the universe there might be a total book***; I beg those unknown gods to have one man – a single man, even if he lived thousands of years ago! – read the book. If this honor and this wisdom and this happiness are not to be mine, may they be others'. May the heavens exist even if my place be in hell. May I be outraged and annihilated, but may in an instant, in a being, Your enormous library be justified.

The impious affirm that such nonsense is normal in the Library and that the reasonable (which is also pure and humble coincidence) is an almost miraculous exception. They speak (I know) of the 'febrile Library, whose hazardous volumes run the unending risk of changing into others, and affirm everything, deny everything, and confuse everything like a divinity who is raving.' These words do not simply denounce the disorder, they also exemplify it and notoriously prove their appalling taste and desperate ignorance. In effect, the Library includes all the variations which the twenty-five orthographic symbols permit, but not a single absolutely foolish act. It serves no purpose to observe that the best volume of the many hexagons which I administer is called Combed thunder; another The cramp of plaster; yet another Axaxaxas mlö. These propositions, at first blush incoherent, are doubtless capable of a cryptographic or allegorical justification; this justification is verbal and, ex hypothesi, is already part of the Library. I cannot combine certain characters

dhcmrlchtdj

which the divine Library might not have foreseen and which do not, in any of its secret languages, entail a terrible meaning. No one can pronounce a syllable that is not filled with tendernesses and fears, that is not the powerful name of a god in one of those languages. To speak is to incur tautologies. This useless and verbose epistle already exists in one of the thirty volumes of the five shelves of one of the uncountable hexagons – as does its refutation. (A number n of possible languages uses the same vocabulary; in some, the symbol library admits the proper definition: ubiquitous and everlasting system of hexagonal galleries. But library is bread or pyramid or some other things, and the seven words which define it have another value. You, my reader, are you sure you understand my language?)

Methodical writing distracts me from the present condition of men. The certitude that everything has been written annuls or haunts us. I know districts in which young people prostrate themselves before books and barbarically kiss their pages, yet they do not know how to decipher a single letter. Epidemics, heretical discords, peregrinations which inevitably degenerate into banditry, all of these have decimated the population. I believe I have already mentioned the suicides, more frequent every year. Perhaps I am deceived by fear and old age, but I suspect that the human species – the only one – is about to make itself extinct and that the Library will endure: illuminated, solitary, infinite, perfectly immobile, armed with precious volumes, useless, incorruptible, secret.

I have just written infinite. I have not interpolated this adjective out of rhetorical custom; I say that it is not illogical to think that the world is infinite. Those who deem it limited postulate that in remote places the corridors, staircases and hexagons will for us inconceivably cease to be – which is absurd. Those that imagine the world without limits forget that it contains the possible number of books. I dare to insinuate this solution of the ancient problem: the library is unlimited and periodic. If an eternal traveler were to cross it in a given direction, he would prove, at the end of the centuries, that the same volumes repeat in the same disorder (which, I repeat, may be an order: the Order). My solitude is lightened by this elegant hope.****

-------------------------------------------

* The original manuscript does not contain figures or uppercase letters. Punctuation has been limited to the comma and the period. Those two signs, the space and the twenty-two letters of the alphabet are the twenty-five symbols sufficient to enumerate the unknown. (Editor's note.)

** Previously, for every three hexagons there used to be one person. Suicide and pulmonary diseases destroyed this proportion. A memory of unspeakable melancholy: at times I have traveled for many nights through polished corridors and staircases without finding a single librarian.

*** I repeat: it is sufficient that a book be possible for it to exist. Only the impossible is excluded. For example: no book is also a staircase, although there are doubtless books which challenge and deny and demonstrate this possibility, and others whose structure corresponds to that of a staircase.

**** Letizia Álvarez de Toledo has observed that the vast Library is useless; in all honesty, a single volume, in the typical format and printed in nine or ten sections consisting of an infinite number of infinitely thin pages, would suffice. (At the beginning of the seventeenth century Cavalieri said that every solid body was the superimposition of an infinite number of planes). Making use of this sleek vademecum would not be easy: each apparent page would double into other analogues, and the inconceivable central page would not have a reverse side.

Saturday, January 31, 2015 at 12:30

Saturday, January 31, 2015 at 12:30  Life's vastness I will have to praise,

Life's vastness I will have to praise,