The Three Students

Tuesday, October 7, 2008 at 20:25

Tuesday, October 7, 2008 at 20:25 There are, we are told by the new priests of the religion of unassailable and unfathomable darkness, a hundred billion suns in each of a hundred billion galaxies in our universe. That these pundits are rounding to the nearest happy figure (one with a comet tail of twenty-two zeros) should tell you exactly how sure we are of what is out there and what might actually be hidden from our perspectives. The students of today are indeed confronted with the dilemma of overspecialization, of realizing from the beginning of their education that they unlike this man of letters or this great philosopher, mathematician and diplomat, cannot possibly learn in a lifetime everything that is worth learning. Instead, they are advised to choose one small, sniveling category as their Bible and pursue that microcosm with all due alacrity and ferociousness, with man's greatest achievement, literature, being no exception. Surely – and I may reveal some prejudices with the following statement – each literary tradition needs its experts. Each language needs diligent men and women gorged on the masterpieces of the tradition in question and sufficiently familiar with everything else of note to derive from this assortment another library of thematic and philological studies. In smaller and newer traditions, however, there inevitably lurks a paucity of works available to the scholar who wishes to place his countrymen (usually these tasks are best left to a native) on the same shelf with the books of great world literature. It has been commonplace in the last century and in this one to speak of major traditions as simply those who have been historically blessed over the course of written time. So the fact that Italy has countless works of art and Slovenia does not (as it were, my grandmother was an ethnic Slovene who spoke both languages) should not make one think that Slovenian literature possesses any less dignity than its Roman neighbor. Yet given our terrestrial limitations, what is worth learning and what isn't? Have I been foolish in my choice of Czech (now long since forgotten) and Danish, two smaller traditions rich in culture? Let us put these questions aside for the moment and turn to this gem of a story that broaches the subject.

![]() From its title, we understand that the tale will involve a university or a school, and likely one of great standing. This suspicion is confirmed in the opening paragraph when Watson informs us that he and his sleuthing chum had the opportunity "in the year '95 ... to spend some weeks in one of our great university towns." Holmes profits from the occasion to frequent a library

From its title, we understand that the tale will involve a university or a school, and likely one of great standing. This suspicion is confirmed in the opening paragraph when Watson informs us that he and his sleuthing chum had the opportunity "in the year '95 ... to spend some weeks in one of our great university towns." Holmes profits from the occasion to frequent a library

Where [he] was pursuing some laborious researches in early English charters – researches which led to results so striking that they may be the subject of one of my future narratives.

Although Holmes's academic interests – tire tracks, ash, poisons, inks, and coded languages, to name but a few – are arcane and often only used to propel the story forward, it is always interesting to see a great mind tackle a subject systematically since true learning can only be gotten from such an approach. Holmes's work is going so well, in fact, that he initially fends off the pleas of a Mr. Hilton Soames, tutor and lecturer at the College of St. Luke's. It turns out that, the following day, Soames will be administering an exam in Ancient Greek (including a sight passage from this famous historian) with the best grade to be awarded a scholarship. Perhaps stupidly, he receives a copy of the Thucydides passage and leaves it unattended on his desk for an hour. When he returns, he finds a key in the lock of his office and, upon entering, the three slips of paper containing the Greek scattered across the room. The only other person with a key is the mild-mannered servant, Bannister, "a little, white-faced, clean-shaven, grizzly-haired fellow of fifty" and "absolutely above suspicion." So the blame must fall to one of the three students for Soames is responsible: Daulat Ras, Miles McLaren, and a young man named Gilchrist.

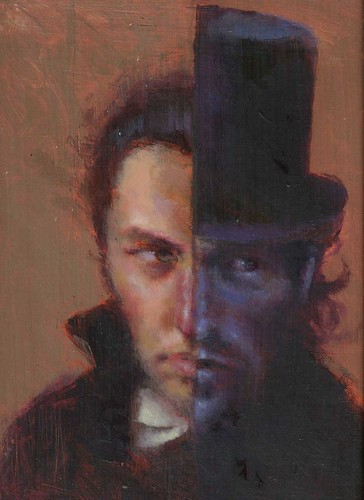

Holmes's methods are simple and elucidating, so no more of the plot will be revealed here. What is most interesting is Conan Doyle's choice of three students, instinctively reflecting three societal currents with which Victorian England as a whole had to contend (women's rights lagged behind just a tad). Gilchrist, who is never mentioned by his Christian name, is the son of the infamous Sir Jabez Gilchrist, a lord of ill repute "who ruined himself on the turf"; Ras, "a quiet, inscrutable fellow," represents the movement of academics from the Indian subcontinent to the best universities of their erstwhile oppressors and the seed of postcolonialism in general; and McLaren is described as "wayward, dissipated, and unprincipled," but "when he chooses to work, one of the brightest intellects of the university." To Conan Doyle's credit, little is made of these differences, and the investigation proceeds more along an examination of personality and motive rather than cultural tendency. Still, we see old England, modern polyethnic England, and modernity's knee-jerk reaction to authority and its preposterous claim to hereditary divine rights. By the way, the only divine rights that exist are common to all of us, and they involve the right to believe in something greater than ourselves. Sometimes that means admitting that we cannot understand our universe in full, but that, to paraphrase this writer of genius, we can begin to grasp the outline of a future understanding. Maybe this sentiment can be pamphletized as follows: read as much as you can, learn as much as you can, but do it with the big picture in mind. Regardless of how many suns you choose to worship.