Benito Cereno

Wednesday, December 4, 2013 at 12:21

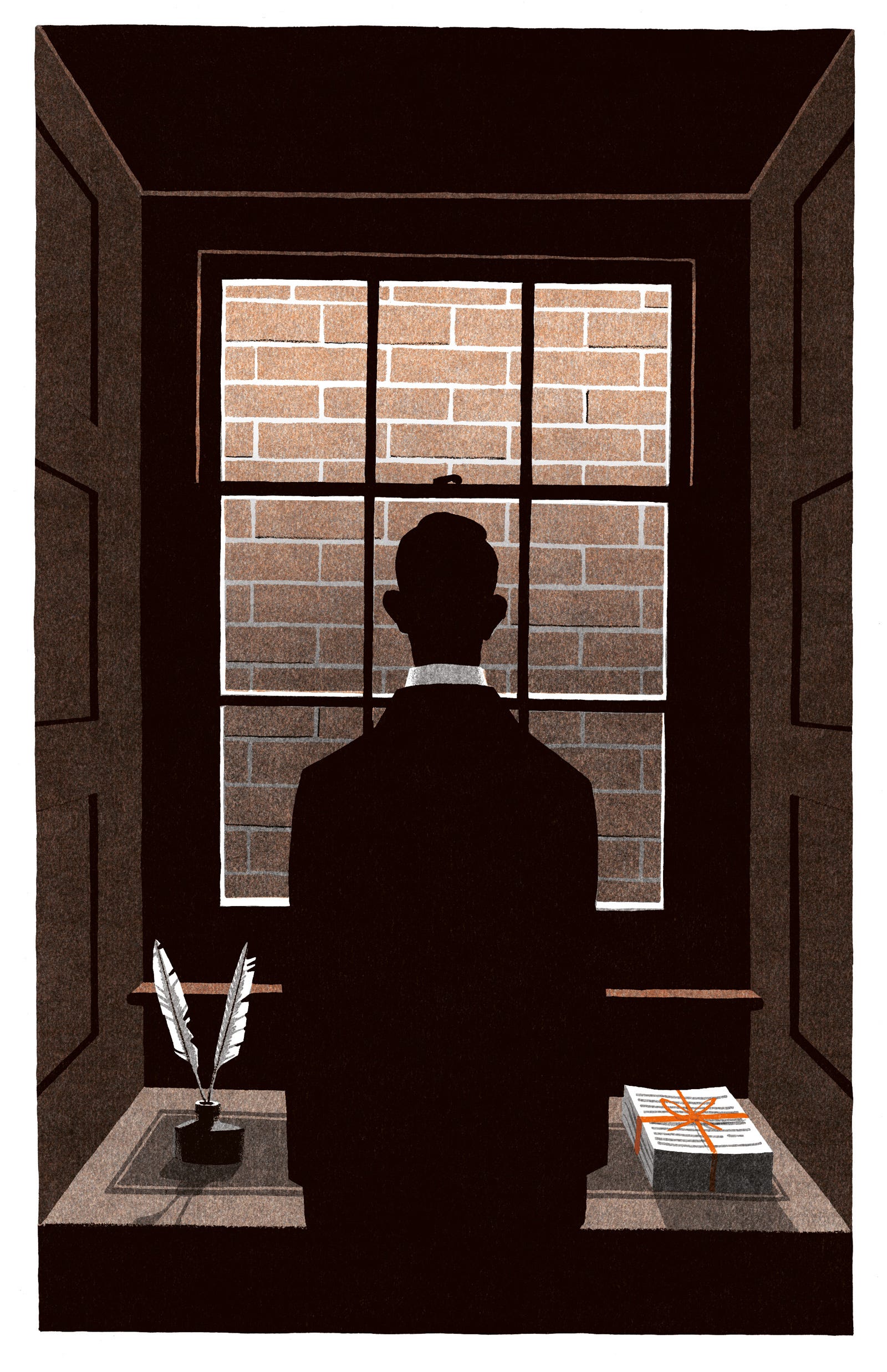

Wednesday, December 4, 2013 at 12:21 Life and its cruel minions have tamed us to see what it wishes. We may walk into a crowded room and think it unfriendly because its occupants are our verbal strangers when in reality each is as lonely and isolated as we think ourselves; we may concoct anecdotal evidence of the locals in our vicinity because our domicile must be distinguished from all other towns at all other times; and we may understand a person's weaknesses by the compliments he grudgingly distributes. Yet, in essence, this is nothing that should surprise us. We are geared and programmed to be benevolent because, whatever those selfish naysayers might believe – and they believe in nothing except deepest, coldest space – faith and goodwill remain our natural disposition. I might not wander into a dark alley for fear of the worst of human predatoriness; but I will trust the young and charming salesperson genuinely persuaded by the reliability of his products, if only until I politely bid him farewell. If trust is our starting point, suspicion is our quiet ally as the smoke of human ambition clouds our judgment. And in this German town several hundred miles from sand and sun I read over two thousand pages on the ocean and its perils, some so obscure as to remain the banter of old sea-dogs. And there is not a little of the incomprehensible in the bold designs aboard the San Dominick in this majestic tale.

We are taken back to 1799 and quite literally the end of the world – "the harbor of Santa Maria, a small desert, uninhabited island toward the southern extremity of the long coast of Chile." Here docks the ship of our protagonist, the American captain Amasa Delano, and his crew of sealers, ostensibly for water but also to experience the heartsease that the coast proffers to the brazen and far-flung. On that same horizon comes "a strange sail":

We are taken back to 1799 and quite literally the end of the world – "the harbor of Santa Maria, a small desert, uninhabited island toward the southern extremity of the long coast of Chile." Here docks the ship of our protagonist, the American captain Amasa Delano, and his crew of sealers, ostensibly for water but also to experience the heartsease that the coast proffers to the brazen and far-flung. On that same horizon comes "a strange sail":

The stranger, viewed through the glass, showed no colours; though to do so upon entering a haven, however uninhabited in its shores, where but a single other ship might be lying, was the custom among peaceful seamen of all nations. Considering the lawlessness and loneliness of the spot, and the sort of stories, at that day, associated with those seas, Captain Delano's surprise might have deepened into some uneasiness had he not been a person of a singularly undistrustful good nature, not liable, except on extraordinary and repeated excitement, and hardly then, to indulge in personal alarms, any way involving the imputation of malign evil in man. Whether, in view of what humanity is capable, such a trait implies, along with a benevolent heart, more than ordinary quickness and accuracy of intellectual perception, may be left to the wise to determine.

Subsequent events reveal that doubts, while in most instances frivolous and self-perpetuating, do indeed have their place. However bleeding his heart might be, Delano's wits quickly notice the destitution of the ship he approaches: the nets are in disrepair, the mix of Africans and Europeans generally gaunt and sickly, and the overarching impression of the ship is of one marooned and "for days lain tranced without wind." At the helm in only the representational sense is the title character of our story, an emaciated Spaniard who in his nervous tics and sways reminds Delano of a "hypochondriac abbot." Yet there are other oddities aboard. Heat, water deprivation, and scurvy have conspired to wipe out all the Spanish officers save the captain, as well as a great number of the Europeans ("wholesale havoc" is the term used); but the Africans incur fewer fatalities. This inequity coupled with Cereno's erratic behavior begin to stab at Delano like the small daggers he thinks he espies glimmering beneath the Africans' clouts. There are also lapsed punctilios in Cereno's manners that suggest he may not be what he claims, neither a captain nor a nobleman of Spanish stock – but Delano wavers from this impression on more than one occasion. He keeps his men on board their vessel, The Bachelor's Delight; he then pursues his interest, including a desire to practice his excellent Spanish, in Cereno and the latter's rather motley crew, until some small happening helps him conclude that what he has hitherto observed may merit greater scrutiny.

The secret of the story of course will not be mentioned here, and it is for the most part a poorly kept one. What Delano ensures we see is the allegory of misrepresentation so artistically outlined as to hint at a massive intrigue. Time and again he returns to Cereno, who acts as the compass on a misty surface:

He recalled the Spaniard's manner while telling his story. There was a gloomy hesitancy and subterfuge about it. It was just the manner of one making up his tale for evil purposes, as he goes. But if that story was not true, what was the truth? That the ship had unlawfully come into the Spaniard's possession? But in many of its details, especially in reference to the more calamitous parts, such as the fatalities among the seamen, the consequent prolonged beating about, the past sufferings from obstinate calms, and still continued suffering from thirst; in all these points, as well as others, Don Benito's story had been corroborated not only by the wailing ejaculations of the indiscriminate multitude, white and black, but likewise – what seemed impossible to be counterfeit – by the very expression and play of every human feature, which Captain Delano saw. If Don Benito's story was throughout an invention, then every soul on board ... was his carefully drilled recruit in the plot: an incredible inference. And yet, if there was ground for mistrusting the Spanish captain's veracity, that inference was a legitimate one.

There is also a plenitude of lush detail: the shield-piece upon the stern recounting a flagitious scene; the clatter at tense moments of a sextet of oakum-pickers; the captain's valet Bobo, who is as much a valet as Delano is a seagull; the shaving methods peculiar to Spaniards; and four unusual, otherwise minor acts of violence that bespeak some terrible truth. Understanding the ethnic categorizations of both Europeans and Africans as the narrow opinions of Delano, an unworldly if eloquent man, may enhance your enjoyment, but it should not spoil the tale's momentum. And what is suspense if not the prolongation of a nightmare that afflicts us like any other plague? Although, from all indications, we would not want to be privy to the nightmares of Benito Cereno.