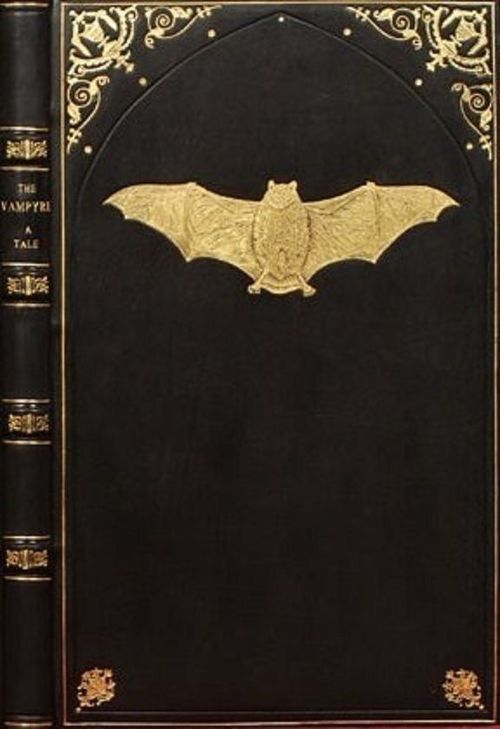

The Vampyre

Tuesday, May 12, 2009 at 09:49

Tuesday, May 12, 2009 at 09:49  There is much to be said for being the first – or, at least, the loudest – in the promulgation of a literary phenomenon. Considering how briefly these phenomena tend to echo within the captive ears of their readership, a topos that has enjoyed two hundred years of uninterrupted (and rising) interest must be termed nothing less than visionary. Perusing the annals of Gothic literature – a genre of writing which has always given me a sort of guilty pleasure – one learns that it was this poet who first formulated, in our modern sense, the monster that has dug its claws into every major literary tradition. Given Byron's elevated assessment of himself that is hardly surprising. Yet despite a lengthy, somewhat overwrought poem in which the beast is described with gory relish, it was not he who first put the real bloodsucker on the map in the dashing, often noble shape for which he is now most renowned, but this half-Italian writer who also died young. And if he gains no other readers for his works and short life in the future, Polidori will be remembered until kingdom come for this classic tale.

There is much to be said for being the first – or, at least, the loudest – in the promulgation of a literary phenomenon. Considering how briefly these phenomena tend to echo within the captive ears of their readership, a topos that has enjoyed two hundred years of uninterrupted (and rising) interest must be termed nothing less than visionary. Perusing the annals of Gothic literature – a genre of writing which has always given me a sort of guilty pleasure – one learns that it was this poet who first formulated, in our modern sense, the monster that has dug its claws into every major literary tradition. Given Byron's elevated assessment of himself that is hardly surprising. Yet despite a lengthy, somewhat overwrought poem in which the beast is described with gory relish, it was not he who first put the real bloodsucker on the map in the dashing, often noble shape for which he is now most renowned, but this half-Italian writer who also died young. And if he gains no other readers for his works and short life in the future, Polidori will be remembered until kingdom come for this classic tale.

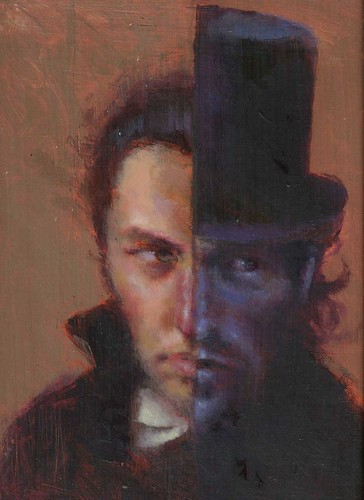

Byron made one other contribution to the legend in a "fragment of a novel" that he wrote almost three years before Polidori's story was published in 1819. A first-person narrator begins to talk about a certain Augustus Darvell, and his attitude is given a curious spin:

He [Darvell] had a power of giving to one passion the appearance of another, in such a manner that it was difficult to define the nature of what was working within him; and the expressions of his features would vary so rapidly, though slightly, that it was useless to trace them to their sources. It was evident that he was a prey to some cureless disquiet; but whether it arose from ambition, love, remorse, grief, from one or all of these, or merely from a morbid temperament akin to disease, I could not discover: there were circumstances alleged which might have justified the application to each of these causes; but, as I have before said, these were so contradictory and contradicted, that none could be fixed upon with accuracy. Where there is mystery, it is generally supposed that there must also be evil: I know not how this may be, but in him there certainly was the one, though I could not ascertain the extent of the other – and felt loath, as far as regarded himself, to believe in its existence. My advances were received with sufficient coldness: but I was young, and not easily discouraged, and at length succeeded in obtaining, to a certain degree, that common-place intercourse and moderate confidence of common and every-day concerns, created and cemented by similarity of pursuit and frequency of meeting, which is called intimacy, or friendship, according to the ideas of him who uses those words to express them.

I include the description in full because the fragment itself is so abbreviated that the rest of it contains but allusions to this primary passage (such is often the case when the germ of an idea has not yet been cultivated into a full-grown flower). However incomplete the characterization, it provided enough impetus for Polidori to expand the story into a cautionary tale of judgment and imposition, one remarkably acute in its portrayal of human weaknesses. The weaknesses, as it were, turn out to be all too familiar: delusion, curiosity, and the unforgivable human predilection to cater to those in positions of power.

In The Vampyre, our mysterious stranger assumes the pseudo-Germanic name of Count Ruthven (which may be loosely etymologized as "friend of suffering"). Yet the stage is set not through the third-person narrator, who knows better than to trust such a baleful being, but by the young Aubrey, a naive landed elite:

He [Aubrey] had, hence, that high romantic feeling of honor and candor, which daily ruins so many milliners' apprentices. He believed all to sympathize with virtue, and thought that vice was thrown in by Providence merely for the picturesque effect of the scene, as we see in romances: he thought that the misery of a cottage merely consisted in the vesting of clothes, which were as warm, but which were better adapted to the painter's eye by their irregular folds and various colored patches. He thought, in fine, that the dreams of poets were the realities of life.

We all know an Aubrey or two, and most usually they are harmless sorts who dream of life as much as they actually observe it. In a society in which little crime or misery can be found, the Aubreys of the world stay sheltered if feckless, and only with time if at all understand that there is more to existence than a lyric poem to the mountains. We should not be astonished, therefore, at the effect that Ruthven has on a person like Aubrey, nor that Ruthven would not hesitate to identify his mark:

He [Aubrey] watched him [Ruthven]; and the very impossibility of forming an idea of the character of a man entirely absorbed in himself, who gave few other signs of his observation of external objects, than the tacit assent to their existence, implied by the avoidance of their contact: allowing his imagination to picture every thing that flattered its propensity to extravagant ideas, he soon formed this object into the hero of a romance, and determined to observe the offspring of his fancy, rather than the person before him.

This is the most telling passage in a story brimming with niceties and victories of style, and it thoroughly accounts for the horrific sequence of events that follow. Aubrey and Ruthven become acquaintances but Aubrey still cannot place what about the Count bothers him so; eventually, he goes to Greece and falls in love with a Greek girl called Ianthe who warns him as all good heroines do not to wander through a dark and gloomy sylvan scene. And like most of the heroes of contemporary horror fiction, Aubrey just does that and comes across a few rather nasty secrets about his former acquaintance.

What obtains through the end of the story is what habitually befalls those who are both outgeneraled and impatient. The special twist in this case, and one that indicates the demonic origins of the Count, is a promise that he extracts from Aubrey even after the youth has been witness to flagitious displays of his power. That Aubrey wavers only slightly might be imputed to the hypnotic clasp of his adversary, although a more cynical mind could easily charge Aubrey with too much optimism in the affairs of man and beast. And Ruthven would surely qualify for both of those epithets.