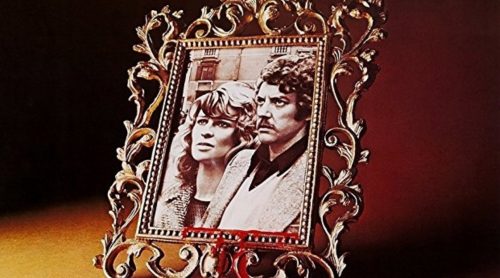

Don't Look Now

Tuesday, August 19, 2008 at 23:27

Tuesday, August 19, 2008 at 23:27  Our tendency when informed that a film is a "horror movie" has developed astride that of modern culture. It used to be that horror meant something otherworldly or eerie (or the German equivalent, unheimlich, which might be loosely etymologized as "not of the home"); this included the usual slew of specters, banshees, ghosts, werewolves, vampires, zombies, and other disfigurations of life that served as foils to our own existence. Now we are confronted with nothing more than disturbed humans, victims of an illness or a horrific childhood, who, as stated in a recent film in a somewhat different context, "just want to see the city burn." They are neither inherently evil nor have they ever really known the Good; they are instead fruit that was rotten upon birth or shortly thereafter and exculpated from any misdeeds they subsequently commit. I have always found this later version of wickedness dull for one very good reason: its perpetrators are not free. Let me correct that: we are not allowed to perceive them as free. They are as much the victims as the hapless fools on whom they vent their inner demons. Whatever the legal loophole or medical reason, they cannot be held responsible for their actions because we are apparently all logical animals who would never kill unless absolutely forced to do so to defend ourselves or our loved ones, although animals kill for many self-serving reasons all the time, not just for food or out of despair. No, these killers are more repulsive than terrifying. It is when you sense a second layer to life, and when that layer is not amenable to your well-being or some sign is being given that you might not understand, that you should be frightened out of your wits. And few films are creepier than this horror classic.

Our tendency when informed that a film is a "horror movie" has developed astride that of modern culture. It used to be that horror meant something otherworldly or eerie (or the German equivalent, unheimlich, which might be loosely etymologized as "not of the home"); this included the usual slew of specters, banshees, ghosts, werewolves, vampires, zombies, and other disfigurations of life that served as foils to our own existence. Now we are confronted with nothing more than disturbed humans, victims of an illness or a horrific childhood, who, as stated in a recent film in a somewhat different context, "just want to see the city burn." They are neither inherently evil nor have they ever really known the Good; they are instead fruit that was rotten upon birth or shortly thereafter and exculpated from any misdeeds they subsequently commit. I have always found this later version of wickedness dull for one very good reason: its perpetrators are not free. Let me correct that: we are not allowed to perceive them as free. They are as much the victims as the hapless fools on whom they vent their inner demons. Whatever the legal loophole or medical reason, they cannot be held responsible for their actions because we are apparently all logical animals who would never kill unless absolutely forced to do so to defend ourselves or our loved ones, although animals kill for many self-serving reasons all the time, not just for food or out of despair. No, these killers are more repulsive than terrifying. It is when you sense a second layer to life, and when that layer is not amenable to your well-being or some sign is being given that you might not understand, that you should be frightened out of your wits. And few films are creepier than this horror classic.

In the very famous first scene, we meet an attractive young couple, John and Laura Baxter (Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie), and their two small children Johnny and Christine. No harm is done to your enjoyment of the film by revealing that Christine drowns in one of the ponds at their large British estate garishly embalmed in a plastic red mackintosh. At almost precisely the same moment, John is staring at a picture of a Venetian church he will spend the rest of the film restoring. On the right-hand side (but the sinister left if one were actually at the altar) is a figure in a red cowl. The figure's back is to John and to us, but the color of the hood is so red that we, just like John, start imagining a crimson gush across the whole picture. John senses something is amiss and runs to find Christine lifeless and crimson (in her coat) in the aforementioned pond. He screams one of those noiseless screams that detonate true anguish and is echoed by Laura's much louder shriek.

They are in a restaurant in Venice when we see them next. Christine died in the fall and this is winter, but the actual timelag is never established. The couple has gone through what can only be described as a living hell, although a stiff upper lip, John's endless work, and a lot of pills for Laura have alleviated some of the pain. They exchange listless niceties about John's church and the food, always a good topic for a stay in Italy, until Laura espies two elderly women staggering towards the bathrooms; they are, like Laura, British, and one of them has something caught in her eye. And here is where the coincidences, if that's what you want to call them, begin to accumulate. It turns out that the two women, Wendy and Heather, are sisters. Wendy can't dislodge whatever got stuck in her eye because Heather, who has some of the deadest, shark-like blue eyes you will ever find, is herself unable to see the physical world. Heather compensates by seeing what we would wish to look into: the psychic world. Her visions are both auditory and visual, but she also senses the beyond in many curious ways (including a later séance which seems to have sexual implications). Of course, we know at once that she will see Christine among her thoughts, a healthy, radiant Christine "sitting between her parents and laughing." Anxious to latch on to anything, Laura believes Heather because of the detailed description of the red mackintosh, which brings us to the subject of red.

The director of Don't Look Now was once the cinematographer on an adaptation of this classic Poe tale in which red represents, literally and figuratively, the end of everything (there is even a billboard exclaiming "Venice in Peril," although no further detail is provided). And why the color red? There is no symbolic meaning other than its unnaturalness, its audacity, its boldness. When Laura finally feels better, she puts on red leather boots and takes along a red purse. But John experiences something drastically different: he begins to see a small, cowled red figure darting between the innumerable Venetian alleys. He is told that there is a killer on the loose, but that red coat reminds him so much of Christine (he even sees her reflection in the water as the figure scampers by) that he cannot decide whether what he sees is a symbol of Good or a harbinger of his own doom. You will hold your breath whenever red enters your purview – it is rather amazing – and you will feel the mounting turpitude in the empty streets, the scowls, the subdued disdain that John and Laura find on every face. There are many faces in the crowd, one of whom is the bishop (Massimo Serato) of the Church that John is restoring, and you do not have to see the film twice to notice something incredibly wrong with this man. I suppose there's a reason the bishop asks Laura whether she is a Christian, and she says she's nice to children and animals because that is what we think of Christians today. The bishop winces at the thought of foul play, although one gets the impression that he owes his annoyance to not having thought of the misdeed himself. "I hope that's not another murder," he says casually as a body is fished out of the canals, while every part of his face and body hints at a mild satisfaction with the outcome.

Yet what is most wonderful about this film is the proximity of its angles: simply anything could jump out from any corner at any time. The buildup, as is the case in any great story of suspense, is painfully slow to the point that you will want what is about to happen more than the characters who are living it (most evident perhaps in the fantastic scaffolding scene, in which we feel as disoriented as the people involved). The camera lingers on doors, corners, windows, empty spaces, and we fill them with our fears. The strange scene in which the bishop is talking at, but not to, a beautiful and ashamed woman sitting across his pious desk; the blind woman going up the steps without any help; the twitch in the deputy's face as John leads the blind woman out of the detention center; the quick interlude where the psychic and her sister are seen cackling in their room as Laura tells John that these "two neurotic old ladies" are helping her get over the tragedy; the bust in the room of the psychic and her sister, a small boy in ebony called Angus, who also died very young; a devilish bust underneath a hood atop what appears to be one of the church's gargoyles, which might foreshadow another scene; the passing, as John discusses the matter with an Italian official, of a couple of old women underneath the official's window as he starts making blasphemously evil doodles on the police drawings of these women; the fact that John is reading this German play about the ills of the Catholic church in the original language. All of these details converge around a statement about John made by one of the characters that he never gets a chance to hear. What he does hear is that the canals sound different to Heather – they sound "like a city in aspic full of dead people after a dinner party," at which point she mentions the greatest of all poets and his love for Venice. All the scenes are linked by virtue of their being gathered together, just like the nightmare whose form they assume. A shame perhaps that such a clever and unusual movie would have such a tepid, almost banal title (you can blame the original work); yet evil, real evil, is always banal. And at the end of this nightmare there is little more than evil.

Reader Comments