L'artiste moderne

Monday, January 31, 2011 at 05:09

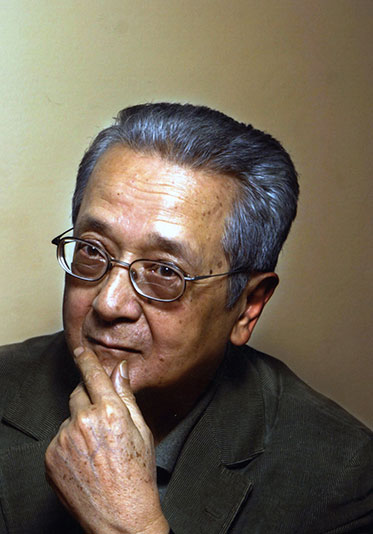

Monday, January 31, 2011 at 05:09 An essay ("The modern artist") by this French poet. You can read the original here.

My dear M****, when you did me the honor of asking for an analysis of Salon, you said: "Be brief, do not compile a catalogue. Give me a general impression, something like a narrative of a spirited philosophical stroll through a gallery." Well then, you will be served heartily, and not because your program agrees (and, as it were, it does agree) with the manner in which these deadly articles in Salon are actually conceived; or because this method may be easier than any other – brevity always takes more effort than prolixity; but because, very simply and most of all in the present case, no other program is possible.

Certainly, my burden would have been greater still if I had been lost amidst a forest of originalities; if the modern French temperament, suddenly modified, purified, and rejuvenated, had yielded flowers so vigorous and of a scent so varied that they would have created irrepressible astonishment, provoked an abundance of praise and chatty admiration, and required the formation of new categories in the critical lexicon. But thankfully (for me) none of this occurred. No explosion; no unknown geniuses. The thoughts suggested by the aspect of this Salon are of an order so simple, so old, so classic, that it would undoubtedly take but a few pages to develop them. So do not be surprised that the banality of the painter engendered the commonplace in the writer. Besides, you would lose nothing in such a belief, for could there be anything more charming (it pleases me to think that we share an opinion on this matter), more fertile, and of a nature more positively exciting than the commonplace?

Certainly, my burden would have been greater still if I had been lost amidst a forest of originalities; if the modern French temperament, suddenly modified, purified, and rejuvenated, had yielded flowers so vigorous and of a scent so varied that they would have created irrepressible astonishment, provoked an abundance of praise and chatty admiration, and required the formation of new categories in the critical lexicon. But thankfully (for me) none of this occurred. No explosion; no unknown geniuses. The thoughts suggested by the aspect of this Salon are of an order so simple, so old, so classic, that it would undoubtedly take but a few pages to develop them. So do not be surprised that the banality of the painter engendered the commonplace in the writer. Besides, you would lose nothing in such a belief, for could there be anything more charming (it pleases me to think that we share an opinion on this matter), more fertile, and of a nature more positively exciting than the commonplace?

Before I begin, allow me to vent one regret that is, I believe, only seldom expressed. We had been informed that we would be receiving guests, and not exactly unknown guests, as the Avenue Montaigne exhibition already made the Parisian public aware of some of these charming artists who had wallowed in anonymity for far too long. For that reason I held a party to renew my acquaintance with Leslie, that rich, naïve, and noble humourist, one of the most accentuated expressions of the British mentality; with the two Hunts, the first an opinionated naturalist, and the second the ardent and witting creator of pre-Raphaelism; with Maclise, the audacious composer, as enthusiastic as he is sure of himself; with Millais, that meticulous poet; with J. Chalon, that mixture of Claude and Watteau, historian of beautiful afternoon events in the great Italian parks; with Grant, that natural heir to Reynolds; with Hook, who knows how to flood his Venetian Dreams with a magic light; with the strange Paton, whose mind veers towards Fuseli and then wanders with the patience of another epoch, that of the graceful chaos of the pantheists; with Cattermole, the watercolor painter of history; with that other fellow, so surprising that the name escapes me now, that visionary architect who on paper can construct cities whose bridges have elephants as columns and let pass between their colossal limbs all the sails of the world, the gigantic three-masted ships! Lodgings for these imaginary friends were even prepared and of a singular color for these favorites of the bizarre muse. But, alas! For reasons which I do not know and whose explanation, I think, cannot be articulated on the pages of your journal, my expectations were disappointed. In this way, tragic ardors, gesticulations in the manner of Kean or Macready, intimate kindnesses of home, Oriental splendors reflected in the poetic mirror of the English mind, Scottish greenery, enchanting freshnesses, and fleeting depths of watercolors like that decor, however small, we will not be able to consider in this "philosophical stroll," at least not this time around. Enthusiastic representatives of the imagination and of the soul's most precious faculties, were you then so poorly received the first time that you might judge us unworthy of understanding you?

In this way, my dear M***, will we be obliged to adhere to France. And please believe that I would experience immense joy in assuming a lyrical tone to speak about the artists of my country. But unfortunately in a critical mind exerted so rarely, patriotism only plays an absolutely tyrannical role, and we have to make some humiliating confessions. The first time I set foot in Salon, I made, on the stairs themselves, the acquaintance of one of our most respected and subtle critics, and to my first question, to that most natural question which I simply had to ask, he responded: "Flat, mediocre; I have rarely seen Salon as bleak." He was at once both wrong and right. An exhibition which possesses a number of works by Delacroix, by Penguilly, and by Fromentin cannot be bleak. But generally speaking I see that his assertion was correct. That mediocrity has dominated every age is indubitable; but that it reigns now more than ever, that it has become absolutely triumphant and cumbersome, this is as true as it is distressing.

After my eyes had wafted for some time over these platitudes put to good use, all this silliness painstakingly polished, all these stupidities or falsehoods so expertly constructed, I of course was led in the course of my reflections to consider the artist in the past and to place him beside the artist of the present. And then the terrible, eternal question arose, as it inevitably did at the end of these discouraging reflections. It seemed like pettiness, puerility, a lack of curiosity, the flat calm of fatuousness have succeeded ardor, nobility, and turbulent ambition, both in the fine arts as well as in literature, and that nothing, for the moment, can furnish us with any hope of the spiritual blossomings as abundant as those of the Restoration. And I am not the only one oppressed by these bitter reflections, believe me, and I will prove it to you at once. So I used to say to myself: back then, what was the artist (Lebrun or David, for example)? Lebrun was erudition, imagination, a knowledge of the past, a love for the great and the magnificent. David, that colossus injured by myrmidons, wasn't he also the love of the past, the love of the great and magnificent united with erudition? And now, what is an artist, that old brother of the poet?

To respond properly to this question, my dear M***, one should not be afraid of being too hard. Scandalous favoritism sometimes provokes an equivalent reaction. The artist today and for a number of years has been, despite his absence of merit, a simple enfant gâté, a spoiled child. What amount of honors, what amount of money have been handed over to these men without souls or learning! Surely I am not averse to the introduction into an art of means that are alien to it; nevertheless, to give one example, I cannot but feel sympathy for an artist like Chenavard, always pleasant, as pleasant as books, and graceful to the point of slowness. At least with him (he may be the target of the plunderer's jokes, what do I care?) I am sure that he speaks of Vergil or of Plato. Préault has a charming gift, an instinctive taste that throws itself upon the beautiful like a predator upon its natural prey. Daumier is gifted with luminous good sense which colors all his conversation. Despite the bewildering leaps of his discourse, Ricard lets us see at every moment that he knows a lot and has taken into consideration a wide number of different sources. It is useless, I think, to speak of the conversation of Eugène Delacroix, which is an admirable mix of philosophical solidity, spiritual lightness, and burning enthusiasm. In addition, I cannot recall anyone else who would be worthy of conversing with a philosopher or poet. Besides, you would hardly find anything more than the enfant gâté. I beseech and beg you, tell me in what salon, in what cabaret, in what earthly or intimate meeting you have ever heard a spiritual word uttered by an enfant gâté – a profound, brilliant, and concentrated word that might make us think or dream, a suggestive word, nothing more! If such a word is uttered, it can only come from a politician or philosopher, or even from someone of unusual vocation – a hunter, a sailor, a taxidermist. But from an artist, an enfant gâté, never.

The enfant gâté has inherited the privilege of his precursors, a legitimate privilege at that time. The enthusiasm that welcomed David, Guérin, Girodet, Gros, Delacroix, and Bonington still illuminates his scrawny person in a charitable light. And while good poets and vigorous historians labor to make a living, the imbecile sponsor pays magnificently for the indecent little stupidities of the enfant gâté. Note that I would not complain if such good fortune befell deserving men. I am not one of those who envy a singer or a dancer who has reached the zenith of her art, a fortune acquired by hard work and daily peril. I fear I may fall into the vice of the late Girardin, of sophisticated memory, which would one day reproach Théophile Gautier for having his imagination cost more than the services of a sub-prefect. This was, if you will remember, during those black days when the public was appalled at hearing you speak Latin: pecudesque locutae! No, I am not unfair to such a degree. And yet it is good to raise a hue and cry over modern stupidity, when in the same period in which a gorgeous painting by Delacroix would have difficulty finding a buyer at a thousand francs, Meissonier's imperceptible figures have gotten ten or twenty times that price. But these lovely days are over: we have slipped even lower, and Mr. Meissonier, who despite all his merits, had the misfortune to introduce and popularize petit bourgeois taste, is a veritable giant compared to our contemporary bauble-makers.

Discredit of the imagination, contempt of the great and magnificent, love – no, this word is too beautiful – exclusive practice of a profession: when it comes to an artist, I believe that these are the principal reasons of his debasement. The more imagination he possesses, the better then must he master his profession so as to accompany his imagination on its adventures and surmount the difficulties which it so avidly seeks. And the better he masters his profession, the less will he boast of it and showcase it, so that his imagination will shine in all its brilliance. This is what wisdom says. And wisdom also says that he who only possesses ability is a beast; and the imagination which he wishes to forsake means he is a madman. Yet however simple things may be, they are above or beneath the modern artist. A concierge's daughter says to herself: "I will go to the Conservatory, I will appear in the Comédie-Française, and I will recite the verse of Corneille until I obtain the rights of those who have recited such verse for a very long time." And she proceeds to do exactly what she said she would. She is very classically monotone and very classically annoying and ignorant; but she has succeeded in that which was very easy, that is, to obtain by patience the privileges of the member.

And the enfant gâté, the modern painter, says to himself: "What is imagination? A danger and a burden. What is the reading and contemplation of the past? Time lost. I will be classic, not like Bertin (since the classic changes place and name), but like ... Troyon, for example." And he proceeds to do exactly what he said he would. He paints, he paints, and he clogs his soul, and he paints some more, until at length he resembles the artist of the moment, and by his stupidity and ability he gains approval and the money of the public. The imitator of the imitator finds his imitators and each of them in this way pursues his dream of grandeur, clogging his soul ever the more tightly, and most of all, not reading anything, not even The Perfect Cook, which nevertheless could have opened up to him a less lucrative but more glorious career. Once he masters the art of sauces, icing, glazing, smearing, juices, and stews (I am talking painting), the enfant gâté assumes proud attitudes and repeats to himself with more conviction than ever that all the rest is useless.

There was a German farmer who came to find a painter and told him: "Mr. Painter, I want you to paint my portrait. You will picture me seated at the main entrance to my farm, in the large armchair bequeathed by my father. At my side you will paint my wife with her bedpost; behind us, coming and going, my daughters who are preparing our family supper. On the large street which runs to the left, some of my sons coming back from the fields after having rounded up the cows into the stable; others, with my grandchildren, are bringing back the carts full of hay. While I am contemplating these sights, do not forget, I beg you, the smoke puffs from my pipe that emerge shaded by the setting sun. I also want the sounds of the Angelus ringing in the neighboring church bells to be heard. It is there that we all got married, parents and children. It is important that you paint the air of satisfaction which I am enjoying at this moment of the day as I contemplate at once my family and my riches augmented by a hard day's work!"

Long live this farmer! Without suspecting it he has understood painting. The love of his profession has elevated his imagination. Which one of our fashionable artists would be worthy of carrying out this portrait, and whose imagination could attain this level?