Thursday

Feb142008

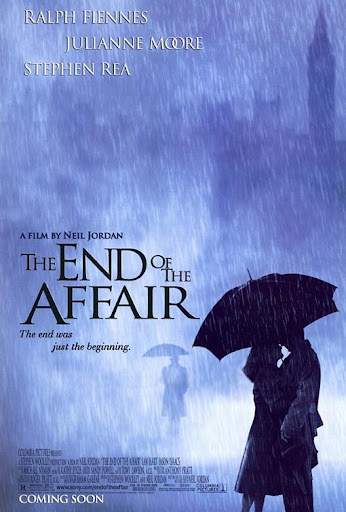

The End of the Affair (film)

Thursday, February 14, 2008 at 16:14

Thursday, February 14, 2008 at 16:14 There is an old adage about serious writers’ contempt for thrillers, detective novels, and other such crime games, and truly, the vast majority of these products do not need our dislike, since their wooden characters, lackadaisical style, and preposterous plotting indicate they already despise themselves. Certainly, they are not meant to be re–read and are as disposable as the brown paper bags in which we carry other guilty pleasures. Yet most of us, I think, enjoy a good mystery if indeed there are still good mysteries to be enjoyed (they are perhaps fewer about than in mystery’s Golden Age, but many page–turners can still be found). The premise behind these works, be they literary or cinematic, is that either something extraordinary or unusual will be revealed to us, or the process by which this revelation is made will be fascinating (in the best mysteries, both these features converge). The thrill of discovering a solution to a complex gambit — or, to be more modern about it, some multi–tiered conspiracy — is very satisfying after a long day of work, and gives us the impression that we are in tune with the shapes and shifts of the world, that our intuition is still sharply honed, and that we have learned from life and can apply these lessons to future days.

In this way, mysteries are the most basic form of literature. They simultaneously explain and amuse, which accounts for the development in the twentieth century of this novelistic form as well as the proliferation of books and films that exploit chicanery, deception, and cabalism to wretched commercial ends. One topic that seems caught in the undertow of this wave of intrigue is actually the most exciting of them all: that of personal mysteries and personal discoveries. Introspection is a nice and trendy word, but it also breeds bellybutton–staring. More acceptable practices are learning about ourselves through others and learning about these same people through ourselves. In other words, mastering the basic recipes of human psychology and then serving them to guests. Some guests (as we have learned) always praise the food, regardless of what they really think; others will only emphasize what could be improved; then there are those most maddening and unreadable types who say nothing and just chew quietly like some lonesome cow. It is not clear whether they are being politely taciturn, whether they are incapable of expressing what they really feel (either good or bad), whether they do not care about food in general and consider it a biological necessity, or whether they do not care about you, the cook, who, in principle, believes in what you are serving and tries to accommodate your guests as best you can. Now make all those guests the romantic interests you have had over the years and make your food emotion and affection, and we come to why today is about love, which is the greatest mystery there could ever be. It is the greatest of mysteries precisely because it involves a continuous revelation of something extraordinary and unusual, and because no solution is ever guaranteed.

In this way, mysteries are the most basic form of literature. They simultaneously explain and amuse, which accounts for the development in the twentieth century of this novelistic form as well as the proliferation of books and films that exploit chicanery, deception, and cabalism to wretched commercial ends. One topic that seems caught in the undertow of this wave of intrigue is actually the most exciting of them all: that of personal mysteries and personal discoveries. Introspection is a nice and trendy word, but it also breeds bellybutton–staring. More acceptable practices are learning about ourselves through others and learning about these same people through ourselves. In other words, mastering the basic recipes of human psychology and then serving them to guests. Some guests (as we have learned) always praise the food, regardless of what they really think; others will only emphasize what could be improved; then there are those most maddening and unreadable types who say nothing and just chew quietly like some lonesome cow. It is not clear whether they are being politely taciturn, whether they are incapable of expressing what they really feel (either good or bad), whether they do not care about food in general and consider it a biological necessity, or whether they do not care about you, the cook, who, in principle, believes in what you are serving and tries to accommodate your guests as best you can. Now make all those guests the romantic interests you have had over the years and make your food emotion and affection, and we come to why today is about love, which is the greatest mystery there could ever be. It is the greatest of mysteries precisely because it involves a continuous revelation of something extraordinary and unusual, and because no solution is ever guaranteed. The setup for this film by renowned director Neil Jordan is the mystery of how people may spend years apart and, upon seeing each other again, be swept up by that same wave and dragged mercilessly down to a bottomless trench. The afflicted is a young novelist called Maurice Bendrix (Ralph Fiennes), and the year is 1946. England has survived the war, or so it claims, and quilts of memories are tattered by the losses that each endured, even in a country that hardly bore the brunt of the destruction. Maurice has lost enough of his sense of idealism and optimism to become surly and resentful towards this new world, and although he maintains a rough exterior, inside he is ravaged. His ravager has long red hair, incomparable cheekbones, and a plain name, Sarah Miles (Julianne Moore). Maurice and Sarah are as old as the war, having begun their love in 1939, and like the war they are over, although Maurice is as haunted by what went wrong in his small, private tragedy that is utterly unimportant for the history of the world as every citizen wondered how in God’s name such a calamity could befall civilization. The most injurious part of Maurice’s pain is his love’s inexplicable termination towards war’s end: he is, as he always will be, in Sarah’s arms, when a shell smashes into his London home. For a few minutes both he and Sarah think they are dead, or, much worse, that only one of them has survived. We are given Sarah’s point of view on this event, and it takes more than a few minutes for her to realize that Maurice is still alive and will probably live. But she leaves, wordlessly, submissively, and cannot or will not explain why she feels this step to be necessary. I should add that she has been married all this time to a rather sympathetic civil servant by the name of Henry (Stephen Rea), and she is still married to him at the beginning of the film when Maurice bumps into Henry one miserably rainy night.

There's a mystery here having to do with Sarah’s reason for leaving Maurice’s house that day, and the reason is both good and ludicrous. To carry out a story of such basic structure requires exquisite acting, which is provided by Moore and Fiennes, but also by Rea, who just wants his wife to be happy and understands she could never be happy with only him. The original novel has components of the time period that allow Jordan’s adaptation to give us flavor without intrusion into the mores of the era (a tactic that is far less successful in the hopelessly anachronistic love affair in the filming of this book). Doubtless, the steady, cuckolded husband is an old cliché, as is the artistic lover who makes life and love more intense, or the seductive beauty caught between duty and passion, and so forth. But there are other details as well, including a small boy with a horrible affliction, that seem at first superfluous but then turn out to be essential. Fiennes and Moore are so skilled at the small gestures and tortures of genuine affection that you will have a hard time believing they are not a real–life couple (this film might well be banned in both actors’ family settings, and not just for the corporalities). You will also marvel at what people in love do for one another, even at the risk of losing them. And that is a mystery that will never be solved.

Reader Comments