Cautiva

Saturday, April 26, 2008 at 03:29

Saturday, April 26, 2008 at 03:29 Watching a rather mediocre Argentinean film recently (which I will not bother to name) reminded me of a far superior production from the same southern land. And the fact that the subject matter is sensitive material cannot be understated: a childhood classmate of mine was a refugee from the regime in question, and that was the sole repeated answer as to why he arrived here with only one parent. You may have also heard of other popularizations of the Disappeared in song and film, and maybe felt a bit indifferent when you discovered the actual number of missing persons. To the families of those made to vanish from God’s green earth, however, the number one is sufficient to elicit irreparable emotional and psychic harm, as well as a dire need for coming to terms with the past and its wickedness. This film — one of, one supposes, many more revelations to come — becomes a cathartic necessity.

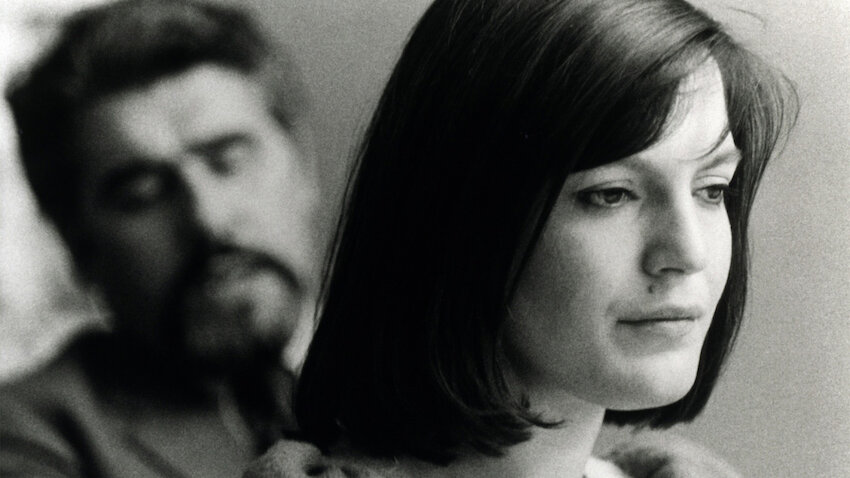

The title translates as “captive,” feminine singular. That prisoner is Cristina Quadri (Bárbara Lombardo), the sixteen−year−old daughter of a police officer (Osvaldo Santoro) and his wife, who leads the normal life of a privileged teenager in one of Buenos Aires’s residential areas. Her dreary but prestigious Catholic school promotes piety and the uniformity of faith in a concerted effort to make all its children feel that they are sheltered by the Lord himself. Or something to that effect. Unlike her classmates, Cristina feels perfectly fine in her skin. She is attractive and smart (otherwise, we fear she would have not made the cut as movie heroine), and compels us in that coy manner that seems to be uniquely a talent of certain younger women. Such girls tend to drift through the first fifteen or twenty minutes of their starring roles distinguishing themselves from their peers, and Cautiva proves to be no exception. Her friend Angélica uses up a few precious moments of the perfunctory introduction trying to make Cristina more like everyone else, which of course in terms of her inexperience and naïveté she is in many ways. The stage is set for a very determined man (Hugo Arana), a judge no less, who whisks Cristina out of her classroom and life hitherto and informs her of something that may scare each of us some dark nights: her precise family origin.

The title translates as “captive,” feminine singular. That prisoner is Cristina Quadri (Bárbara Lombardo), the sixteen−year−old daughter of a police officer (Osvaldo Santoro) and his wife, who leads the normal life of a privileged teenager in one of Buenos Aires’s residential areas. Her dreary but prestigious Catholic school promotes piety and the uniformity of faith in a concerted effort to make all its children feel that they are sheltered by the Lord himself. Or something to that effect. Unlike her classmates, Cristina feels perfectly fine in her skin. She is attractive and smart (otherwise, we fear she would have not made the cut as movie heroine), and compels us in that coy manner that seems to be uniquely a talent of certain younger women. Such girls tend to drift through the first fifteen or twenty minutes of their starring roles distinguishing themselves from their peers, and Cautiva proves to be no exception. Her friend Angélica uses up a few precious moments of the perfunctory introduction trying to make Cristina more like everyone else, which of course in terms of her inexperience and naïveté she is in many ways. The stage is set for a very determined man (Hugo Arana), a judge no less, who whisks Cristina out of her classroom and life hitherto and informs her of something that may scare each of us some dark nights: her precise family origin.

What follows can only be expected, an expurgation of one existence in favor of a life stolen before consciousness kept notes of the events in its vicinity. As a child, says Judge Barrenechea, Cristina belonged to someone else. Her parents had the sensational opportunity of doing what so many around the world long to do, but few dare: standing in defiance of an oppressive and inhumane government. And like the majority of these brave millions they targeted an enemy infinitely more adept at inflicting punishment and shame than they were. So Cristina’s parents, activists in the latter half of the 1970s when a whole generation of open−minded Argentines was erased by organized and covert evil, were subjected to brutality. As a result, Cristina was orphaned while still incapable of speech or independent movement; in fact her birth mother had given her another name, Sofia. We know and are reminded of the persistence of so many children of the disappeared among the survivors of the purges that even a righteous crusader like Barrenechea, who hoots and pontificates unabashedly as the angel of vengeance, could never hope to find much less prosecute those responsible. At least, he says to himself, I can tell the truth and set these children free.

And what of the “adoptive” parents? How complicit must you have been (you were, after all, a law enforcement official in the heyday of the secret police) to receive the kickback of an entire human being left to be molded and educated only by you and your wife, who cannot have your own children? That last question is not only mine, it is the angry query directed at the Quadris by the daughter they raised as their own child. The question is addressed from a different viewpoint in an earlier and much more famous film, but here things evolve from the perspective of the child herself. Cristina does not need to stand for such nonsense. Being of age, she can choose to forsake the only parents she has ever known, reclaim the name on her long−since−destroyed birth certificate and represent a symbolic denial of the theft of both identity and life that occurred only thirty years ago. Yet how many children do you know that would willingly assume this thankless burden of responsibility? What child is mature enough in spiritual strength to act as an example of redemption that has only signs and symbols to play with? What would you or I have done in a similar situation and at a similar age? Perhaps exactly what Cristina ends up doing, which I cannot reveal. Whatever her choice, the one thing she will retain is the title of a captive forever beholden to the truth, as will the generations this truth continues to affect. That is not much, but sometimes the truth is small and cruel and completely unbearable.