Closer

Tuesday, November 14, 2017 at 13:07

Tuesday, November 14, 2017 at 13:07 In the course of this film, the youngest of the four protagonists – and the one supposedly least wise about the world – describes an exhibition as "a collection of sad strangers photographed beautifully, which leads the glamorous patrons who attend these types of exhibitions to think the world is happy." Admittedly, she uses a term far less flattering than "patron," but her insight amidst a nonstop stream of semi-profound statements and banal truths has a broader horizon that is hardly matched. Is the world really a miserable place, and artists (especially photographers and filmmakers, who make more direct use of their subjects) simply exploiters of the downtrodden to make themselves feel better about their privileges? This line of thinking has long been the battle cry of those who rail against art as superfluous and reduce the world to a compost of primal needs and disorders, bereft of any spirituality, any beauty, or anything more elevated than their own graying heads (this wretched lot knows who they are and should stay clear of these pages). But this is not exactly what the above quote means; or at least, it is not all it means. It also indicates that the artist and pessimist will never share the same tramcar much less the same soul. To achieve great art means believing in art, and believing in something inessential to the lusty cravings and itches of terrestrial existence means hoping that time will redeem your labor and crown it with immortality. Or perhaps we should just make do with aphorisms such as "you've got to respect the fish. We were all fish once," as another of our protagonists avers (somehow, this same character will later announce that, "without the truth, we are nothing but animals")? Like the title suggests, an examination of the film should not dawdle on the surface.

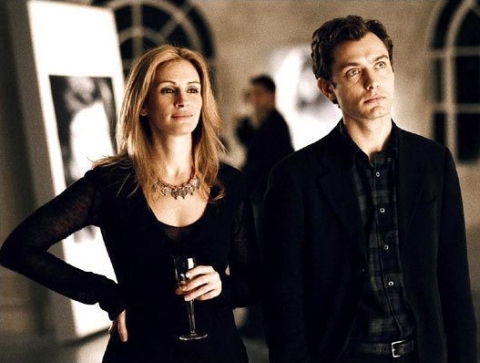

Our characters are four, a love trapezoid that provides gender balance: Dan Woolf (Jude Law), a failed writer and obituarist; Alice Ayres (Natalie Portman), a lost soul and waitress with a sordid past; Anna Cameron (Julia Roberts), a professional photographer; and Larry Grey (Clive Owen), a dermatologist. Both the women in our quartet are American, while both men are British, and the action takes place on the men's home turf. Unlike the all-too-popular hyperlink films in which the lives of strangers are interwoven by only showing us certain segments of their interaction, our protagonists are bracing themselves from the very beginning for a four-way head-on collision. Appropriately, Dan meets Alice when the latter is almost run over by a London motorist (a sure sign of an American), and when he takes her to the hospital unnecessarily, the cab driver asks him whether the young, bleeding woman he's holding in his arms is his, to which he replies in the affirmative. They begin a long relationship despite their age difference (about ten years or so; the actors themselves are nine years apart), lack of common interests, and general discrepancy in culture. That last assertion might seem a bit snobbish on my part, yet it is owing precisely to that unbridgeable gap that Dan finds himself attracted to Anna, who possesses the quiet, introspective tendencies of someone dedicated first and foremost to an art form. There is also the matter of Alice's previous line of work, which involved very little clothing, a fire pole, and dim lighting – an early admission that guides Dan's hand, so to speak. She's a stripper, the opposite of what we want in a woman, the opposite of art, because we want to earn every naked woman we see because we are ourselves, and not because we happen to own multicolored papers with holograms and famous dead people that can be traded, at our whims, for almost anything in the world. Even if Alice were not embroiled in something more debauched than stripping, the seed has been planted in Dan's idealist mind: my girlfriend is, was, or could very well become a prostitute, and he immediately looks for something purer among the pagan hordes.

Our characters are four, a love trapezoid that provides gender balance: Dan Woolf (Jude Law), a failed writer and obituarist; Alice Ayres (Natalie Portman), a lost soul and waitress with a sordid past; Anna Cameron (Julia Roberts), a professional photographer; and Larry Grey (Clive Owen), a dermatologist. Both the women in our quartet are American, while both men are British, and the action takes place on the men's home turf. Unlike the all-too-popular hyperlink films in which the lives of strangers are interwoven by only showing us certain segments of their interaction, our protagonists are bracing themselves from the very beginning for a four-way head-on collision. Appropriately, Dan meets Alice when the latter is almost run over by a London motorist (a sure sign of an American), and when he takes her to the hospital unnecessarily, the cab driver asks him whether the young, bleeding woman he's holding in his arms is his, to which he replies in the affirmative. They begin a long relationship despite their age difference (about ten years or so; the actors themselves are nine years apart), lack of common interests, and general discrepancy in culture. That last assertion might seem a bit snobbish on my part, yet it is owing precisely to that unbridgeable gap that Dan finds himself attracted to Anna, who possesses the quiet, introspective tendencies of someone dedicated first and foremost to an art form. There is also the matter of Alice's previous line of work, which involved very little clothing, a fire pole, and dim lighting – an early admission that guides Dan's hand, so to speak. She's a stripper, the opposite of what we want in a woman, the opposite of art, because we want to earn every naked woman we see because we are ourselves, and not because we happen to own multicolored papers with holograms and famous dead people that can be traded, at our whims, for almost anything in the world. Even if Alice were not embroiled in something more debauched than stripping, the seed has been planted in Dan's idealist mind: my girlfriend is, was, or could very well become a prostitute, and he immediately looks for something purer among the pagan hordes.

When he goes for a photo shoot to Anna's – Anna wants to take pictures of more ordinary people, perhaps hinting to Dan where he stands – they end up molesting one another, although Anna is obviously not interested and coming off a separation from her first husband. This indifference may not be obvious to a first-time viewer, but repeated examinations of Closer leave no doubt. Anna wants to be desired by Dan; she wants a nice, unsuccessful person to make her feel better about her burgeoning career (she is a few years older than the obituarist); but most of all, she wants someone who understands that artists can be the most gracious and the most selfish people in the world, oftentimes within the same mortal form. Dan, of course, is attracted to her creative mystique, her sullen devotion to her trade, and her mature acceptance of why life can be so painful. They do not advance past that first, teenagerish session, but as the months accumulate, Dan cannot let go of what he is missing with Anna because he is missing so much in Alice. Finally, via "the internet, the first great democratic medium" (Anna's bold words), Dan attaches Anna to the fourth point on our compass, Larry, a self-proclaimed "clinical observer of the human carnival." Despite his good looks and career, Larry cannot seem to find any happiness among all the young women who would stab their sister in the sternum to go out with a handsome dermatologist, not to mention the non-comedogenic advice that such a relationship would yield. The vulgar chatroom scene in which Larry is cajoled by "Anna" to meet her at an aquarium the next day will tell you everything you need to know about why Larry is alone. In any case, they meet, awkwardly, and – unbeknownst to a horrified Dan – start to date. Four months into their relationship, Anna has her exhibition, where Alice and Larry and Dan all converge, especially around the large picture of Alice in which she is noticeably teary-eyed, and which provokes the bitter quotation that began this review.

Even if you are unfamiliar with Patrick Marber's original staging, it is obvious that Closer was initially a play: there are, apart from a few quick moments, only four characters and they all talk far too much. This is the opposite of an adaptation of a novel, where quotations from the book are so decontextualized as to seem either utterly pretentious or utterly nonsensical (one particularly egregious offender is this film). Yet chatty plays are naturally inferior products because all of us have contexts when we talk to anyone, even to strangers; in fact, it is these contexts that lead to the majority of misunderstandings between people who have never spoken to each other before and, in all likelihood, will never converse again. The acting in Closer fluctuates from very good to phenomenal (Owen, who played the Dan Woolf character in the original play, is particularly superb), and carries a rather plain story to the precipice of excellence, contorting, along the way, banal truths into actual tidbits of insight about our four creatures. Dan goes back to the exhibition that fateful evening because he can't stay away from someone with equal artistic tendencies ("I haven't even seen you for a year," Anna claims coyly); Larry, on the other hand, is a physical beast, a man of science whose specialization is quite literally the surface of us all. The mismatching is fantastic, because it is exactly how so many couples operate, identifying something that doesn't belong to them as something that they desperately need. Even the music when partners are swapped is telling: Larry enters to something industrial in a club that screams carnality, while Anna and Dan meet at a rendition of this famous opera (inducing some critics to think that the opera and our film have some parallels, which might be pushing it a bit). The ending contains a couple of nice twists, and is relieved from one inevitability by the insistence of the male characters, in typical gender tendency, on knowing details that they probably shouldn't know. What type of details, you may ask? The details that allow you to hate or love someone so intensely that it devours your consciousness. And some people should really learn that asking questions ultimately leads to unpleasant truths. Maybe that's why animals usually look so happy.