The Mystery of Marie Rogêt

Friday, October 7, 2016 at 10:13

Friday, October 7, 2016 at 10:13 Nothing is more vague than impressions of individual identity. Each man recognizes his neighbor, yet there are few instances in which any one is prepared to give a reason for his recognition.

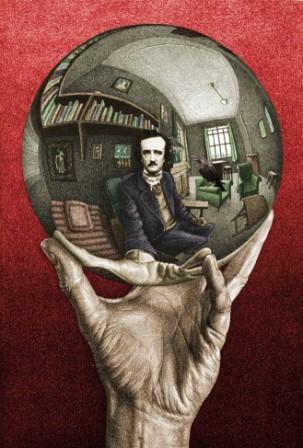

You may have heard of a recent film with the name of a masterpiece; you will surely know the inspiration for what critics have almost uniformly understood as an excuse – albeit a clever and original one – to allow yet another serial killer to wreak havoc on the national census. Perhaps this is what remains of minds like Poe's (many self-proclaimed admirers of Lovecraft, for example, praise his 'gory science fiction plots,' or other such nonsense) to those who cannot appreciate the sonic rapture of his prose – I know and care not. A true lover of literature preserves deep in his memory the enchantments of the best works of a given author and finds, in time, that certain authors can be trusted and certainly simply cannot. Those who love topicality, who are inspired by the latest hue and cry, can and should be returned to the shelf whence they came and left to rot. Only the authors who consider their own works and own genius eternal, bereft of the shackles of the news hour, are worth our time. Which brings us to a famous literary experiment.

The crime involves a sumptuous young Parisian who helped her mother run a pension until the age of twenty-two, "when her great beauty attracted the notice of a perfumer." The latter obviously has a saleswoman in mind, at least for the business side of things, but we do not. As readers of literary fiction discerning enough to enjoy Poe, we expect that something romantic if not diabolical will absorb poor Marie Rogêt. Now if a pretty young woman is discovered by one man, she will be discovered by dozens of others, because nothing is more beguiling to a man than a woman on whom other men have their eye. It can be concluded therefore that Marie Rogêt, at the time of the onset of this 'mystery,' had become a favorite among those Parisian men lucky enough to frequent the 6th arrondissement. She had gotten herself engaged to one of those men, a certain St. Eustache, who had actually taken up residence in the Rogêts' pension (which commitment came first is left to the reader to surmise), and one fine morning in June she had informed that same St. Eustache that she would be visiting an aunt about two miles away. Thus our story unravels:

The crime involves a sumptuous young Parisian who helped her mother run a pension until the age of twenty-two, "when her great beauty attracted the notice of a perfumer." The latter obviously has a saleswoman in mind, at least for the business side of things, but we do not. As readers of literary fiction discerning enough to enjoy Poe, we expect that something romantic if not diabolical will absorb poor Marie Rogêt. Now if a pretty young woman is discovered by one man, she will be discovered by dozens of others, because nothing is more beguiling to a man than a woman on whom other men have their eye. It can be concluded therefore that Marie Rogêt, at the time of the onset of this 'mystery,' had become a favorite among those Parisian men lucky enough to frequent the 6th arrondissement. She had gotten herself engaged to one of those men, a certain St. Eustache, who had actually taken up residence in the Rogêts' pension (which commitment came first is left to the reader to surmise), and one fine morning in June she had informed that same St. Eustache that she would be visiting an aunt about two miles away. Thus our story unravels:

St. Eustache ... was to have gone for his betrothed at dusk, and to have escorted her home. In the afternoon, however, it came on to rain heavily; and, supposing that she would remain all night at her aunt's, (as she had done under similar circumstances before,) he did not think it necessary to keep his promise. As night drew on, Madame Rogêt (who was an infirm old lady, seventy years of age,) was heard to express a fear ‘that she should never see Marie again’; but this observation attracted little attention at the time. On Monday, it was ascertained that the girl had not been to the Rue des Drômes; and when the day elapsed without tidings of her, a tardy search was instituted at several points in the city, and its environs. It was not, however, until the fourth day from the period of disappearance that anything satisfactory was ascertained respecting her. On this day (Wednesday, the twenty-fifth of June), a Monsieur Beauvais, who, with a friend, had been making inquiries for Marie near the Barrière du Roule, on the shore of the Seine which is opposite the Rue Pavée St. Andrée, was informed that a corpse had just been towed ashore by some fishermen, who had found it floating in the river. Upon seeing the body, Beauvais, after some hesitation, identified it as that of the perfumery-girl. His friend recognized it more promptly.

St. Eustache will leave one of literature's most magnificently described farewell notes ("Upon his person was found a letter, briefly stating his love for Marie, with his design of self-destruction"), which does not, of course, preclude him from possible involvement. What follows this and similar paragraphs lifted from all the newspapers of the day is a quilt of speculation and hysteria that the renowned Auguste Dupin will spend the second half of the story tearing asunder from the friendly confines of his sitting room. Without revealing his methods, which are as usual pedantic in a most enlightening manner, one aside remains particularly trenchant:

The town blackguard seeks the precincts of the town, not through love of the rural, which in his heart he despises, but by way of escape from the restraints and conventionalities of society. He desires less the fresh air and the green trees, than the utter license of the country. Here, at the road-side inn, or beneath the foliage of the woods, he indulges, unchecked by any eye except those of his boon companions, in all the mad excess of a counterfeit hilarity – the joint offspring of liberty and of rum.

The town blackguard? What town blackguard? Our year was 1844 and we still tended in that era to blame small, roving bands of criminals for all the ills of society while robber barons were becoming billionaires and slaves still roaming plantations. The curious reader may discover the rest for himself.

It has been often lamented that The Mystery of Marie Rogêt is the weakest of the Auguste Dupin adventures, and, on the whole, one of Poe's least flavorful works. Yet Poe is one of the few writers whose style is invariably impeccable; his subject matter, however, may be of dubious value. His fascination with the macabre cannot be conveniently explained away by his use of laudanum, nor by some psychological perversions (his marriage to a thirteen-year-old cousin is commonly cited) concocted by some very modern and very ignorant minds. No, Poe had all the attributes of literary genius – style, precision, strong opinions, touchiness regarding any criticism in his direction, and something we can loosely term a sadistic streak. Literary genius thrives in tragedy, not comedy or the doldrums of historical codswallop (as one writer famously quipped, every author should make horrible things befall his fictional underlings to see what they are made of). We are mortal beings and the implications of this limit should and do scare the writer of genius into a labyrinth of unending nightmares. What he finds therein depends principally on what lies in his own soul. Even if it be entrapped in blackest night.