A Mother

Sunday, May 14, 2017 at 13:25

Sunday, May 14, 2017 at 13:25 Miss Devlin had become Mrs. Kearney out of spite. She had been educated in a high-class convent, where she had learned French and music. As she was naturally pale and unbending in manner she made few friends at school. When she came to the age of marriage she was sent out to many houses where her playing and ivory manners were much admired. She sat amid the chilly circle of her accomplishments, waiting for some suitor to brave it and offer her a brilliant life. But the young men whom she met were ordinary and she gave them no encouragement, trying to console her romantic desires by eating a great deal of Turkish Delight in secret. However, when she drew near the limit and her friends began to loosen their tongues about her, she silenced them by marrying Mr. Kearney, who was a bootmaker on Ormond Quay.

We forget sometimes that our most fundamental relationships – parent, child, sibling – are the bases for all other relationships, romantic or office, temporary or everlasting. Those of us lucky enough to enjoy a happy, stable childhood – and happiness and stability are the foundations of life, all life – can only wonder at the broken promises that others have endured. Having children is no easy task, and one that to some should never be assigned; but when children are present, when a couple has created a perfect little mammal or welcomed such a being previously bereft of such caretakers, all thoughts should be geared towards the benefit of the children. No longer are we husbands and wives and sons and daughters and brothers and sisters: we are simply parents, mothers and fathers. And while not everyone, for a variety of reasons, may have a father, every single being on earth may claim the title character of this story.

We forget sometimes that our most fundamental relationships – parent, child, sibling – are the bases for all other relationships, romantic or office, temporary or everlasting. Those of us lucky enough to enjoy a happy, stable childhood – and happiness and stability are the foundations of life, all life – can only wonder at the broken promises that others have endured. Having children is no easy task, and one that to some should never be assigned; but when children are present, when a couple has created a perfect little mammal or welcomed such a being previously bereft of such caretakers, all thoughts should be geared towards the benefit of the children. No longer are we husbands and wives and sons and daughters and brothers and sisters: we are simply parents, mothers and fathers. And while not everyone, for a variety of reasons, may have a father, every single being on earth may claim the title character of this story.

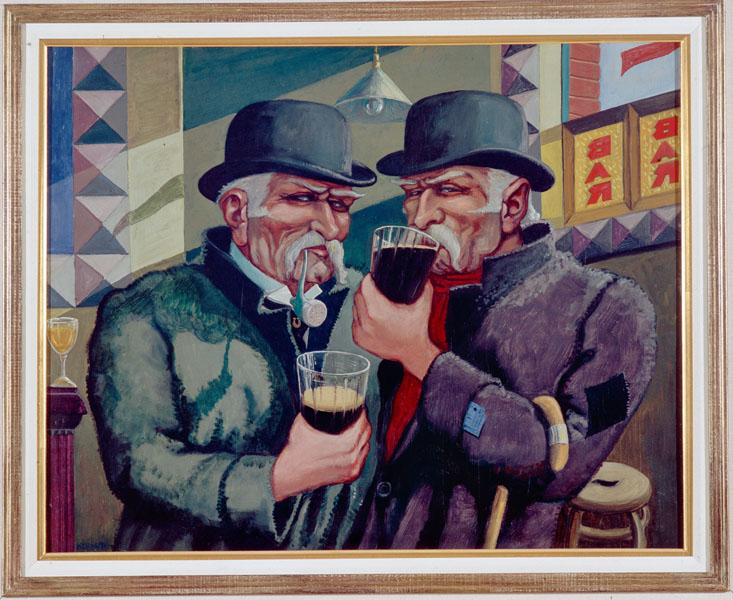

It may seem strange that we are concerned with a mother, when the focal point of our tale is the performance of a certain Kathleen Kearney, the elder of two daughters of Mrs. Kearney, née Devlin. Kathleen Kearney has the type of name that can "be heard often on people's lips," because some names lend themselves to savoring. By dint of her very marketable appellation, her mother's own insistence, and some veritable musical talent, Kathleen Kearney becomes "the accompanist at a series of four grand concerts." These concerts, to be held in Dublin, are sponsored by the Éire Abú Society, which I am afraid means something rather dull in Irish (and only appears to exist in Joyce's fictional realm). As the concert days approach, all consecutive, with the fourth on the very fateful evening of Saturday, Mrs. Kearney, who should not be mistaken for a person of culture, has high hopes for her daughter's performance. That first night she meets the secretary of the Society, who will represent everything she is hoping to overcome:

In the dressing-room behind the stage she was introduced to the secretary of the Society, Mr. Fitzpatrick. She smiled and shook his hand. He was a little man, with a white, vacant face. She noticed that he wore his soft brown hat carelessly on the side of his head and that his accent was flat. He held a programme in his hand, and, while he was talking to her, he chewed one end of it into a moist pulp. He seemed to bear disappointments lightly.

Mrs. Kearney, it should be noted, does not bear disappointments lightly; in fact, she does not expect to have to bear them at all. Disappointments, for a snobbish social climber like Mrs. Kearney, are the lives of those without grace, without ambition, and, most importantly perhaps, without the proper connections to put that grace and ambition to best use.

Things, of course, get worse for our eponymous matriarch. The Wednesday concert provokes the blasphemous suggestion that perhaps the Society "had made a mistake in arranging for four concerts: four was too many"; on Thursday, "the audience behaved indecorously as if the concert were an informal dress rehearsal"; and by Friday morning, someone has seen enough of the first concerts to use "special puffs in all the evening papers reminding the music-loving public" that Kathleen Kearney will be accompanying some impressive artistes the following night. The following night? After the apathy of the Wednesday and Thursday audiences, it was decided by the Society that Friday's would be even less attentive, a logic that would bankrupt the sturdiest of entertainment enterprises, but that is not ours to ponder. And so, a day before their daughter's third and final appearance on the Dublin stage, Mrs. Kearney reveals her suspicions to that "bootmaker on Ormand Quay" who bestowed his surname upon her:

He listened carefully and said that perhaps it would be better if he went with her on Saturday night. She agreed. She respected her husband in the same way as she respected the General Post Office, as something large, secure, and fixed; and though she knew the small number of his talents she appreciated his abstract value as a male. She was glad that he had suggested coming with her.

The phrase "she appreciated his abstract value as a male" in a modern work would seem, and would very likely be, wholly disingenuous; but in Joyce's context there can be no more accurate a description. What ensues that rainy Saturday night will not surprise readers accustomed to those vicissitudes of human nature that may be loosely termed "aesthetic sensibilities" (we will leave the matter at that). We will likewise not address the role of Mr. O'Madden Burke, whose ridiculous name swathes a most ridiculous figure, one which, of course, is "widely respected" by simple-minded people who think spruce, pompous frauds are something to which to aspire. What we should examine, however, is one of the artistes whom Mrs. Kearney surely cannot appreciate:

The bass, Mr. Duggan, was a slender young man with a scattered black moustache. He was the son of a hall porter in an office in the city and, as a boy, he had sung prolonged bass notes in the resounding hall. From this humble state he had raised himself until he had become a first-rate artiste. He had appeared in grand opera. One night, when an operatic artiste had fallen ill, he had undertaken the part of the king in the opera of Maritana at the Queen's Theatre. He sang his music with great feeling and volume and was warmly welcomed by the gallery; but, unfortunately, he marred the good impression by wiping his nose in his gloved hand once or twice out of thoughtlessness. He was unassuming and spoke little. He said yous so softly that it passed unnoticed and he never drank anything stronger than milk for his voice's sake.

Mr. Duggan, you see, is precisely what a mother would want in a child, because he has fulfilled his potential to a sensational level, all the more impressive an accomplishment given the banal hurdles of poverty. And yet, among the innumerable Philistines of grand society, an imaginary community staffed almost entirely by such vulgarians, all that will be remembered of him will be his nose and his gloved hand. The same gloved hand that will one day inherit the earth, the air, and the sea.