Youth Without Youth

Thursday, April 27, 2017 at 09:29

Thursday, April 27, 2017 at 09:29 There is a notion that people are not intimidated by great intelligence, but by great ideas presented intelligently. If you tell someone that religion can be boiled down to ten irrefragable commandments, or loving the one you're with, or the eternal return, or something that can fit on a business card or fortune cookie roll, they will smile because they have been initiated into one of the astounding mysteries of our world. It would be sad yet dutifully accurate to inform them, however, that the average person, even if somewhat well-read, would need at least ten years of intense study, incredible enthusiasm, and some cerebral propitiousness to be able to produce a first-rate book on religion or on literature. Of course, political correctness proclaims that all opinions are worth hearing and all viewpoints, regardless of education or perspective, are worth understanding. This I do not deny; these voices all have the same dignity, the dignity of human thought and feeling. But they do not have the same value. For value, you need minds who know their subject backwards, forwards and, in the case of this lush and beautiful film, also upside-down.

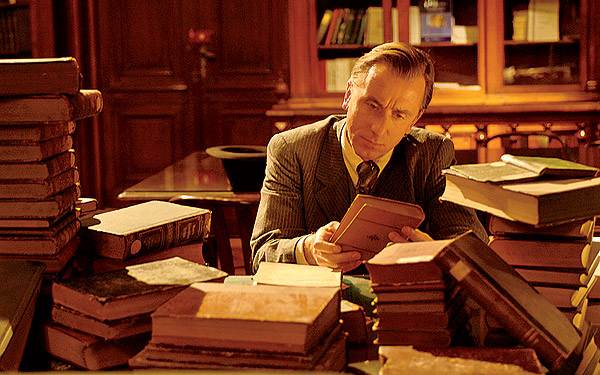

Our hero is Dominic Matei (Tim Roth), a seventy-year-old Romanian scholar who wakes up one evening in the spring of 1938 and realizes that he "will never complete [his] life's work," that work being the chronicling of the origins of language. He decides, quite logically perhaps, to hasten this eventuality. As he potters around a meek Bucharest that already seems to hear the crunch of Fascist boots, Dominic is lifted off the ground, scorched by lightning, then dropped unceremoniously to wither and die. So violent and unexpected is this scene that it sets the tenor for the rest of Youth Without Youth: what has just happened is a miracle of miracles, thus disbelief is necessarily suspended. He winds up mummified in an intensive care station where he signals his name and age by squeezing the hand of Dr. Stanciulescu (Bruno Ganz), yet the nurses who wash his crisped body giggle in his presence and only half-jokingly claim that this man is still very young. In short order we learn the truth: right before Dominic awakes, his image in a nearby looking-glass opens its eyes, soon to be met by those of the original Dominic, now young, handsome and completely unscarred from his encounter with a million heavenly volts. If we weren't already convinced by the fulminous scene outside this train station, we now know that what we are watching is science fiction.

And yet perhaps this is still not the right term. The old Dominic inhabits many flashbacks: he loved a young woman named Laura (Alexandra Maria Lara) who essentially leaves him because he has not fulfilled his potential; he is also a diligent student of Chinese who is dismissed by a French-speaking professor (likely patterned after this Swiss linguist) because without a mastery of Chinese, Tibetan, Sanskrit, and Japanese, he would not take him on as a student. "To master Chinese," says the smug old fellow, twirling his moustaches, "you must have the memory of a mandarin" – which is precisely what the new Dominic acquires. Soon he is able to know the contents of any book simply by willing himself to know them; he can predict the final destination of a roulette ball, move objects by telekinesis, and absorb information at a capacity that can only be called unearthly. He also keeps himself company, literally and figuratively, by discussing his agenda and feelings with a psychic double of himself. If this sounds ridiculous, you may consider that while he has now exceeded all men in pure intellect, he has not lost the human need for conversation with a peer. Stanciulescu publishes a series of incredible reports in a medical journal that garners the attention of scientists around the world. One of these observers has a notebook marked with a wicked symbol that will be mirrored (in perhaps an overlong shot) on the garters of "the woman in room six who was placed there by the secret police." That symbol has now become the most important in Europe, much more vital than all those Chinese characters and all the mathematical equations and all the plethoric knowledge with which Dominic has stuffed his rejuvenated brain. In other words, if that symbol survives, Europe perishes.

As the war rages on in favor of that symbol, Dominic flees to Switzerland, but he cannot exist as anonymously as he would have hoped. At a professorial gathering of leading Swiss scholars ("I knew more than each of them; I knew things that they didn't even dream existed") he is again accosted by that lovely young lady from room six who just so happens to worship that repulsive, all-important symbol and who tells him of a Doctor Monroe ("He's Swiss. Like me. Like you"). When she adds, "you know, I do have a name," he refuses this feeble stab at humanity because the knowledge of her body was no different than the countless books he absorbed, pure information. Monroe, for his part, is interested in running a million volts through some test subjects for the sake of science – and I think you might guess who foots his laboratory bills. To the film's credit, once Dominic extricates himself from this situation, there is a drastic shift in both time and tone, with the second half of the film outyelling its predecessor and continuing Dominic's spiritual journey in ways he could not possibly have imagined. And since they are beyond his own horizon, at least initially, we too will struggle to grasp why Laura seems to have been reincarnated in a young student by the name of Veronica, and why this may not be the only exemplar of metempsychosis that Dominic will witness.

While I am galled by the chocolate box of accents in English among the cast members, however realistic that has now become in the world (I invariably prefer unanimity of dialect), I should add a few words on the negativity of many of the film's reviewers. Youth without youth was a critical failure, particularly in America, for one very good reason: it holds almost no universal appeal. That some reviewers even stooped to labeling the film kitsch reveals a fundamental ignorance of aesthetic theory. Kitsch (and the closely related Russian term poshlost') tugs at the emotions by reducing them to the solution to all plot developments and all questions of character. A Hollywood film that pumps soft music against a still softer sunset and the embrace of two extremely good-looking young people who have only exchanged platitudes for two hours as bombs and bones detonated around them is the epitome of kitsch. Kitsch expects you the viewer to relate to the on-screen happenings because these emotions and lives and loves and hopes are common to all people at all times, and therein lie its eternal sadness and purported – and utterly fraudulent – artistic credentials. All this has absolutely nothing to do with the plight of Dominic Matei. The youth regained embodies the cerebral life Dominic always wanted, and it is his and his alone. He is granted by some Almighty force the time necessary to finish his life's work (a plot device probably borrowed from this famous tale), but then realizes that while he may conclude his intellectual existence satisfactorily, he will never again be a happy, love-struck youth, whereas precisely the opposite predicament would feature in a film devoted to cheap schmaltz. What is legitimately and artistically tragic in Youth Without Youth is that the wisdom and memories Dominic accumulated in the years before the lightning do not permit him to enjoy things with the same sense of invincibility that usually accompanies our early adulthood. He may be young in body but within him shudders the tortured soul of an immortal who has outlived every love and passion. And what can we say about those three roses? Only that Laura may not be one of them.