In Cold Blood

Wednesday, October 14, 2015 at 07:43

Wednesday, October 14, 2015 at 07:43 It was ideal apple-eating weather; the whitest sunlight descended from the purest sky, and an easterly wind rustled, without ripping loose, the last of the leaves on the Chinese elms. Autumns reward western Kansas for the evils that the remaining seasons impose: winter's rough Colorado winds and hip-high, sheep-slaughtering snows; the slushes and the strange land fogs of spring; and summer, when even crows seek the puny shade, and the tawny infinitude of wheatstalks bristle, blaze.

We have all heard the story (we may have even seen the movie – true, there have been several, but only one stands out), yet in our jaded era, when news has devolved into a summary of the day's wickedest and corniest deeds, we may no longer think often about the Kansas night of November 15, 1959. We may no longer wonder what motivated two recent jailbirds to ignite a nationwide manhunt, or how close they were on numerous occasions to not fulfilling their evil scheme. We may also not remember the speedy trial and windy series of appeals, that these two men sat on death row, what was dubbed the Corner in Kansas, for four years before their hanging in 1965. And once all persons immediately involved in the Holcomb tragedy were deceased ("four shotgun blasts that, all told, ended six human lives"), one of America's finest prose works was finally printed to everlasting controversy and acclaim.

We begin in one of the westernmost regions of the Bible Belt, "that gospel-haunted strip of American territory in which a man must, if only for business reasons, take his religion with the straightest of faces." The residents of these quiet nooks, like the two-hundred-seventy-odd inhabitants of Holcomb, Kansas, are the direct descendents of those courageous souls who decided once upon a time that a covered wagon on a straight path of destiny was superior to a restricted semi-urban community of property owners. The irony, of course, is that the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of these lonesome prairie doves are now some of the most prominent landowners in their fiefdoms. One such squire is the eminently respectable Herbert Clutter. Clutter is the father of four, getting his only son and heir on the last try. His children are successful – the two eldest daughters have already married well and the youngest and the son are promising high school students – and his marriage has held up despite his wife's chronic infirmity, what some nowadays may choose to characterize as a violent pendulum between two distant poles – but we need not belabor the matter. Perhaps the mild disappointment of the Clutters' matrimony can be best summarized by a typical vista from the lonesome cliff that was Herbert's wife, Bonnie:

We begin in one of the westernmost regions of the Bible Belt, "that gospel-haunted strip of American territory in which a man must, if only for business reasons, take his religion with the straightest of faces." The residents of these quiet nooks, like the two-hundred-seventy-odd inhabitants of Holcomb, Kansas, are the direct descendents of those courageous souls who decided once upon a time that a covered wagon on a straight path of destiny was superior to a restricted semi-urban community of property owners. The irony, of course, is that the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of these lonesome prairie doves are now some of the most prominent landowners in their fiefdoms. One such squire is the eminently respectable Herbert Clutter. Clutter is the father of four, getting his only son and heir on the last try. His children are successful – the two eldest daughters have already married well and the youngest and the son are promising high school students – and his marriage has held up despite his wife's chronic infirmity, what some nowadays may choose to characterize as a violent pendulum between two distant poles – but we need not belabor the matter. Perhaps the mild disappointment of the Clutters' matrimony can be best summarized by a typical vista from the lonesome cliff that was Herbert's wife, Bonnie:

She knew 'good days' and occasionally they accumulated into weeks, months, but even on the best of the good days, those days when she was otherwise her 'old self', the affectionate and charming Bonnie her friends cherished, she could not summon the social vitality her husband's pyramiding activities required. He was a 'joiner,' a 'born leader'; she was not, and stopped attempting to be. And so, along paths bordered by tender regard, by total fidelity, they began to go their semi-separate ways – his a public route, a march of satisfying conquests, and hers a private one that eventually wound through hospital corridors.

Until the night of November 15, 1959, this unbridgeable gap – and it most certainly is unbridgeable – was the worst thing ever to have happened to Herbert Clutter and his immediate family. Alas, almost no one picks up In Cold Blood to learn about Herbert and Bonnie Clutter, their youngest daughter Nancy, or their only son Kenyon. No, readers have flocked to the novel for the better part of five decades because of two deadbeat thirtysomethings: Perry Smith and Dick Hickock.

Four lives – thriving, prosperous lives, albeit undescribed to us in anything except careful bromides – were ended on an unwilled miscalculation; two others, we are shown and told in monumental detail, are the knotty sums of long years of frustration, exclusion, and defeat. The defeated are Smith, a half-Cherokee, half-Irish "dwarfish boy-man" who loves playing the guitar and lifting weights, and Hickock, the sex-crazed check bouncer. Smith's childhood was wanton, hungry, and streaked with cruelty and misfortune; Hickock, on the other hand, was loved and never poor, if restricted by Puritan mores and an unyielding paterfamilias. Smith will compensate for his pain in the most natural way possible: he will seek to educate himself on the books he was never given (his highest education was the third grade) and become a knower of life; Hickock will make up for what he viewed as an iron fence around his stifled adolescent urges by slipping into statutory rape and kleptomania. Keen observers of human nature will immediately note how commonly such an odd couple forges a bond of, if not friendship, then mutual need. Indeed, towards the end of our terrible tale, Smith and Hickock will be joined on Kansas's death row by a similar, if even younger duo, whose motives are somewhat different ("We hate the world," they declare, after massacring seven residents of it) but whose identical demises will come only ten weeks later.

Of our pair of evildoers, Hickock has far less to offer, but he will also bring up an interesting twist in his case that makes his lot seem – at least to him and a few misguided partisans – quite unfair. Regardless of Hickock's machinations this is without a doubt the Perry Smith show. Smith has rage within him, rage that has accumulated over a lifetime of a drunken, cowardly mother, a wild, destitute, and criminal youth, and an appearance that has always generated scorn and distance. Two of his siblings committed suicide and he has mulled over such an exit on countless occasions with no small amount of relief. The plot to rob the Clutters was supposed, however, to bring him happiness and money – two things Smith has never really had, and certainly not at the same time. But happiness is not really the fate of Perry Smith. And so, aboard a Mexican boat with a German captain during the duo's brief but exotic flight from the Kansas killing fields, we get a rather haunting portrait:

When Perry sang, Otto sketched him in a notebook. It was a passable likeness, and the artist perceived one not very obvious aspect of the sitter's countenance – its mischief, an amused, babyish malice that suggested some unkind cupid aiming envenomed arrows. He was naked to the waist. (Perry was 'ashamed' to take off his trousers, 'ashamed' to wear swimming-trunks, for he was afraid that the sight of his injured legs would 'disgust people' and so, despite his underwater reveries, all the talk about skin-diving, he hadn't once gone in the water.)

Smith's injuries date back to a motorcycle "crackup" – but we are not concerned with his well-being, his constant knee-rubbing that begins to resemble a wringing of the hands, or his aspirin-popping that begins to resemble the drugs so typical of the loser and recidivist. When an incarcerated Smith sees from his window cats "hunting for dead birds caught in the vehicles' engine grilles" and recognizes that "most of my life I've done what they're doing; the equivalent," we nod at this soft moment of self-awareness. Even if it is one of the very few.

The years following the publication of In Cold Blood were not that kind to Capote, who began to investigate bottlenecks and tumblers with the same vigor he once devoted to his semi-fictitious creations. But what of the problem of content? Art is necessarily about life; it may, like life, conclude in some form of extinguishment, like the snuffing out of a candle or its gradual guttering into the thinnest glaze of wax. But Capote's masterpiece is about the opposite of life, what we generally know as physical death but which, in this context, may be best understood as a study in extinction. Still, even solely on the basis of one "non-fiction novel" Capote must rank among the twentieth century's foremost prose stylists. Consider the asides: "Dick's anger had soared past him and struck elsewhere"; "His confidence was like a kite that needed reeling in"; "Mrs. Clare, an admirer of logic, although a curious interpreter of it"; "Her [Nancy's] eyes ... darkly translucent, [were] like ale held to the light"; "It was as though [Dick's] head had been halved like an apple, then put together a fraction off center"; "Tomorrow the aged Chevrolet was expected to perform punishing feats"; "Maturity, it seemed, had reduced her [Bonnie's] voice to a single tone, that of apology." Then there was the time a wounded, enlisted Smith hit it off with his nurse:

Sexual episodes of a strange and stealthy nature had occurred, and love had been mentioned, and marriage too, but eventually, when his injuries had mended, he'd told her goodbye and given her, by way of explanation, a poem he pretended to have written.

This magnificent snippet contains more artistic insight than an entire harlequin romance, and just as much plot. At another instance Capote refers to the greenest of the Kansas prosecutors as "an ambitious, portly young man of twenty-eight who looks forty and sometimes fifty" – and I am hard pressed to find a more dazzling portrait of genius amidst a museum of extraordinary exhibits ("I walked miles, my nose bleeding like fifteen pigs" may be a close runner-up). In the end, we are encouraged by justice because the crimes are the most unpardonable and merciless that man can commit. Yet what knowledge could have been gained during the "ideal apple-eating" season? Perhaps simply that of disobedience, neither first nor last. As Nancy stated of her beloved father, "I just want to be his daughter and do as he wishes." If only we all took such words to heart.

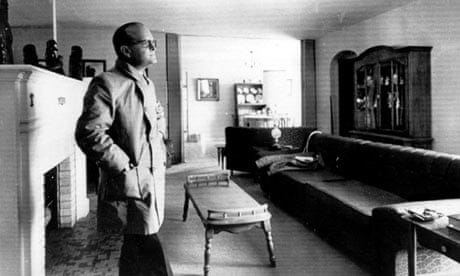

Capote in

Capote in  Book reviews,

Book reviews,  English literature and film

English literature and film