Le bonheur dans le crime (part 1)

Thursday, February 23, 2012 at 15:37

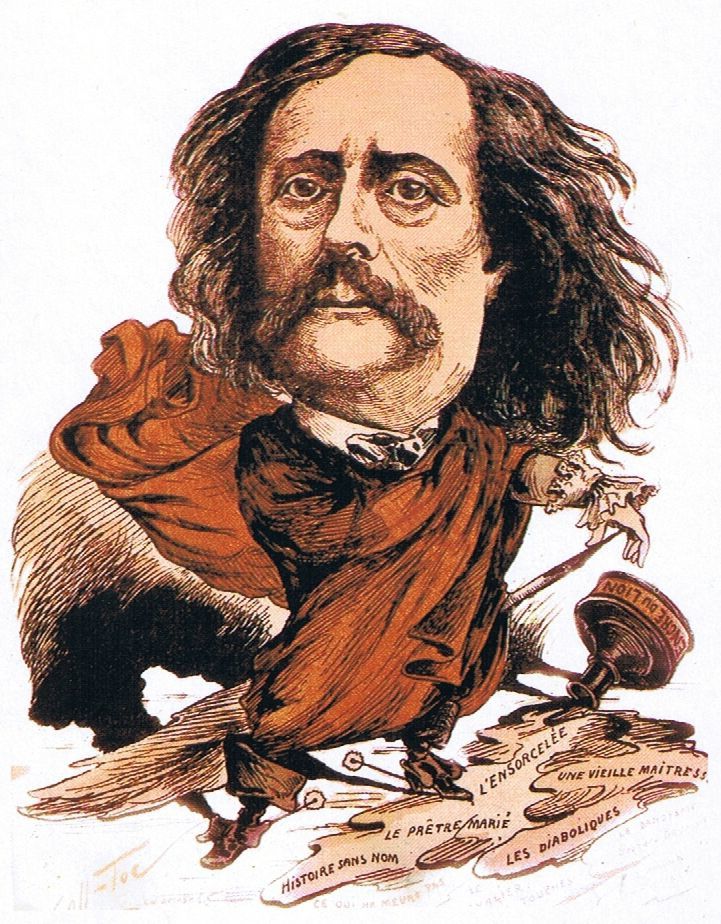

Thursday, February 23, 2012 at 15:37 Part one of a story ("The happiness in crime") by this French writer. You can read the original here.

At those delicious times when there is a true tale to tell, one may well believe that it was the Devil who dictated it.

One morning last autumn I was out strolling in the Jardin des Plantes in the company of Dr. Torty, certainly one of my oldest acquaintances. When I was still but a child Dr. Torty practiced medicine in the city of V.; but after about three decades of this enjoyable occupation, with all his patients now dead – his farmers as he liked to call them, those who had brought him more than most farmers bring their masters, on the best lands in Normandy – he had not taken on any others. Already getting on in age, and swelling with independence like an animal who had always stepped on his bridle and eventually snapped it, he had come to immerse himself in Paris, I believe, there in the vicinity of the Jardin des Plantes, rue Cuvier. Now only for his own personal enjoyment did he practice medicine, in which, as it were, he still took great pleasure because he was a doctor in his blood and bones, and, moreover, an excellent physician and a great observer. Not to mention his many other straightforward physiological and pathological cases.

Perhaps you've had, on several occasions, the opportunity to meet Dr. Torty? He was one of those bold and vigorous spirits who did not wear fingerless mittens for the very good and proverbial reason that a "gloved cat does not get the mouse." He had always borrowed an immense amount, and always sought to take more, from that wily race, so powerful and so fine. He was the type of man I liked a lot, and I firmly believe (after all, I know myself!) that I liked him for precisely those qualities with which he most displeased others. In fact, he was displeasing enough when he behaved himself, this brusque, original figure, Dr. Torty. But once those who most disliked him fell ill, they would salute him with Salaams, as the savages saluted Robinson Crusoe's rifle which could kill them – not for the same reason as the savages, but for, as it were, the opposite reason: he could save them! Without this overriding consideration, the doctor would have never gained twenty thousand pounds of annuity in a small, devout, aristocratic and prudish town, which would otherwise have stranded him at his carriage door before its hospices, had it listened even briefly to his opinions and unfriendly sentiments.

Perhaps you've had, on several occasions, the opportunity to meet Dr. Torty? He was one of those bold and vigorous spirits who did not wear fingerless mittens for the very good and proverbial reason that a "gloved cat does not get the mouse." He had always borrowed an immense amount, and always sought to take more, from that wily race, so powerful and so fine. He was the type of man I liked a lot, and I firmly believe (after all, I know myself!) that I liked him for precisely those qualities with which he most displeased others. In fact, he was displeasing enough when he behaved himself, this brusque, original figure, Dr. Torty. But once those who most disliked him fell ill, they would salute him with Salaams, as the savages saluted Robinson Crusoe's rifle which could kill them – not for the same reason as the savages, but for, as it were, the opposite reason: he could save them! Without this overriding consideration, the doctor would have never gained twenty thousand pounds of annuity in a small, devout, aristocratic and prudish town, which would otherwise have stranded him at his carriage door before its hospices, had it listened even briefly to his opinions and unfriendly sentiments.

This, however, he realized; and as he always maintained a high level of composure, it amused him. "They had to choose," he said mockingly, "between me and the Extreme Unction. And devout as they all were, they preferred me even to the chrisms." As you can see, the doctor was not annoyed: he had a slightly sacrilegious sense of humor. An unabashed disciple of Cabanis in medical philosophy, he was, like his old comrade Chaussier, of that terrible school of physicians devoted to absolute materialism. And like Dubois – the first of the Dubois – to a cynicism which degrades all things, is immediately overfamiliar with duchesses, and addresses the Empress's ladies of honor as "my little mothers," neither more nor less than what he would have said to fishmongers' wives. To provide you with an idea of Dr. Torty's cynicism, it was he who said to me one evening in the circle of the Ganaches, lustfully taking in with a dominating glance the dazzling quadrilateral of a table and its one hundred and twenty guests: "It is I who makes all of them!" Moses could not have been more proud, exhibiting the baton with which he changed rocks into fountains. "What do you want, Madam?" – he did not have any phrenological bump for respect. He even claimed that precisely where it could be found on the skull of other men, there was merely a hole in his own.

Old, already past seventy, but square, robust and as gnarled as his name; of a sardonic face and, under his very smooth, very glossy light brown wig and very short hair, of a penetrating eye, unsullied by glasses; almost always dressed in grey or that shade of brown which for a long time was known as "Moscow smoke," he did not resemble the physicians of Paris in style or dress: proper, white-tied like the shrouds of their death! He was a different man. With his buckskin gloves, his thick-soled boots with high heels which resounded with his unsteady step, there was something alert and cavalier about him. Yes, cavalier's the word, because he had remained (for many more years than thirty!) with his military riding pants buttoned on the thigh, and on horseback as if he were on the warpath to break some centaurs in two. And one divined all this from the way he still arched his back and large chest, screwed on to kidneys that had not moved and balanced on strong legs free of rheumatism that arched like those of a former postman. Dr. Torty was one of those leatherstocking equestrians, who had lived in the mires of the Cotentin as Cooper's leatherstocking had inhabited the forests of America. He was a naturalist who, like the hero in Cooper, scoffed at the laws of society, but like Fenimore Cooper's man had not replaced them with the idea of God. He had become one of these ruthless observers that could not but be a misanthrope. This is fatal, and so it was. He only had the time, while he was making his horse's bloody belly drink the mud of crooked, wrong paths to plough through the other mires of life. This was not a misanthrope like Alcestis. He did not become indignant virtuously; he did not become angry – no! He despised man as quietly as he took his pinch of tobacco, and enjoyed doing both in equal measure.

Such a person was he exactly, this doctor Torty, with whom I was strolling.

That day happened to fall in one of those gay and clear autumn periods that deterred the swallows from leaving. At noon Notre-Dame sounded, and the solemn ringing of its bell appeared to pour out above the green, moiré river and its piers and bridges; and just above our heads the jostled air was pure, trembling long and brightly. The garden's red foliage was, by degrees, wiped clean from the blue fog that drowned them on these vaporous October mornings, and a lovely, late autumn sun pleasantly warmed our backs with a wad of gold. The doctor and I had stopped to look at the famous black panther, who would die the following winter like a young girl from an ailment in its chest. Scattered here and there were the usual visitors to the Jardin des Plantes, that special demographic segment of soldiers and children's nannies who loved gawking before the cages' grid and amusing themselves by tossing walnut shells and chestnut peelings to drowsy animals and those sleeping behind their bars. We had arrived before a panther lurking in his cage who was, if you recall, of that species unique to the island of Java, the country in which nature was at its most intense. Indeed, the entire land seemed itself to be some great tigress, untameable by man, whom it fascinates and bites in all the manifestations upon its terrible and splendid soil. In Java flowers are imbued with more brightness and fragrance, fruits with more taste, animals with greater beauty and power than in any other country on earth. And nothing can convey an idea of this violence of life to those who have not experienced firsthand the harrowing and deadly sensations of a realm at once enchanting and poisonous, at once Armida and Locusta! Casually spreading her elegant legs before her, her head upright, her emerald eyes unmoving, the panther was a magnificent specimen of the redoubtable creations of her country. Not a patch of brown besmirched her fur of black velvet – a black so deep and so dull that the light, in sliding off it, did not itself shine but was instead absorbed like water is drunk up by a sponge ... When, from this ideal form of supple beauty, of terrible force at rest, of impassive and royal disdain, our gaze returned to the human creatures who were looking at it timidly, who were contemplating it with round eyes and gaping mouth, it was not humanity who had it easier, it was the beast. And she was so superior that it was almost humiliating! I was making a comment to that effect in sotto voce to the doctor when two people suddenly split from the group gathered before the panther and planted themselves right before her. "Yes," replied the doctor, "but now watch! The balance between the species will be reestablished!"

These two were a man and a woman, both tall, and from the first look I cast upon them I had the impression of belonging to the elite ranks of the Parisian world. Neither one nor the other was young, but nevertheless they were perfectly beautiful. The man had to be going on forty-seven if not more, and women on at least forty. Thus they had, as the sailors back from Tierra del Fuego might say, passed the line, the fatal line, more wonderful than the equator, which once passed one may never pass again on the seas of life! But they seemed to be hardly concerned about this circumstance. Nowhere, on their brow or anywhere else, were there signs of melancholy.

Slender and with a patrician air in his tightly buttoned black frock coat like that a cavalry officer, as if he were wearing one of the costumes that Titian bestowed upon his portraits, the man looked, by his hooked shape, both effeminate and haughty, his moustache like the whiskers of a cat that had begun to grey at the tip, a fop from the time of Henry III. And to make the similarity even more complete, he had short hair, which in no way prevented a glimpse of the two dark blue sapphires that shone in his ears. They reminded me of the two emeralds that Sbogar wore in the same place. This ridiculous (as people would have said) detail notwithstanding, which showed enough disdain for the tastes and ideas of the day, everything was simple and dandy as Brummell would have wished – that is to say, unremarkable – in the dress of this man who only drew attention on his own merits. And he would have seized our attention completely had he not been on the women's arm, which, at this time, he was.

Indeed, the woman gained more attention than the man who accompanied her, and she captivated us longer. She was as tall as he was, her head almost reached his. And as she was also dressed all in black, she recalled, in the extent of her shape, in her strength, and in her mysterious pride, the large black Isis of the Egyptian Museum. A curious thing: when one approached this beautiful couple it was the woman who had the muscles, and the man who had the nerves! I could only discern her profile; but the profile is either the pitfall of beauty or its most brilliant certificate. Never, I think, had I seen beauty purer or haughtier than hers. As for her eyes, I could not judge, fixed as they were on the panther, which, no doubt, received from them a magnetic and unpleasant impression. Already unmoving, the panther seemed to be sinking more and more into this rigid immobility as the woman, having come to behold the beast, looked at it. And, like those cats caught in blinding light, without its head budging an inch, with only the fine end of its whiskers trembling, the panther, after having blinked several times and being unable to take it any more, slowly withdrew, beneath the casings of its eyelids, the two green stars in its gaze, as if it were shutting itself away.

"Ho, ho, ho, panther against panther!" said the doctor in my ear. "But the satin panther is stronger than the velvet."

The satin panther was the woman, who had on a dress of this shimmering fabric, a dress with a long train. And the doctor's vision had not betrayed him! Black, supple, as powerful in articulation as she was royal in attitude, of equivalent beauty in her own species and of a still darker charm, the woman, the stranger, was a human panther, erect before the panther animal that she dwarfed – which was what the beast sensed, no doubt, when it had closed its eyes. But the woman – if she were indeed one – was not satisfied with this triumph. She lacked generosity. She wanted her rival to open its eyes and look upon its humiliator. And so, undoing without a word the twelve buttons of the purple glove that cast her beautiful forearm, she took off this glove and, audaciously passing her hand between the bars of the cage, whipped the short snout of the panther, who made but one movement – but what a movement! A snatch of teeth as fast as lightning! A scream came from the group where we were standing: we all thought the wrist had been bitten off. But it was merely the glove – the panther had devoured it. Outraged, the magnificent beast had reopened its horribly dilated eyes and its nostrils pulsated even more.

"Are you mad!" said the man, who had seized this beautiful wrist, which had just escaped the sharpest of bites.

You know sometimes how we say "are you mad"? He said it precisely that way; and then he kissed the wrist angrily.

As he was on our side, she turned three quarters of the way to behold him kissing her naked wrist, and I caught a glimpse of her eyes... Those eyes that fascinated tigers were at present fascinated by a man; her eyes, two large black diamonds, designed for all the dignities of life that expressed more in looking at him than all adorations. They expressed love!

Those eyes were there and they contained a poem. The man had not let go the arm, which must have tasted the panther's feverish breath, and, holding it folded on his heart, he led the woman through the large walkway of the garden. They crossed it quietly, all the while indifferent to the murmurs and the heckling from the masses who were still emotional over the danger that the reckless woman had just run. As they passed by the doctor and me, their faces were turned towards one another, huddled flank against flank as if they wanted to enter each other, he in her and she in him, and from the two of them create a single body by looking at nothing but themselves. Observing them walking by in this manner one would have said they were higher, superior creatures who did not even perceive in their toes the land on which they walked, and who crossed the world in their cloud as did, in Homer, the Immortals.

Such things are rare in Paris, and for this reason we remained there to watch them leave, this master couple: the woman dragging the black train of her dress through the garden's dust, like a peacock, dismissive even of its plumage.

As they moved away in this manner, beneath the rays of the noonday sun, in the majesty of their intertwining, these two beings were superb. And at length they regained the garden gate's entrance and clambered into a coach, glittering brass and coupling, that had been waiting for them.

"They have forgotten the universe!" I said to the doctor, who understood my way of thinking.

"Ah, they care quite a lot about the universe!" he replied in his biting voice. "They see nothing in creation, and, what is even more damning, they even walk by their own physician without seeing him."

"What? You, doctor!" I shouted. "But then, my dear doctor, you are going to tell me who they are."

The doctor made what is called a pause with the desire of producing an effect, because he was cunning in everything, the old devil!

"Well," he said simply, "they are Philemon and Baucis. There you are!"

"Damn it all!" said I. "Philemon and Baucis, with a proud appearance and hardly resembling their ancient namesakes. But doctor, these are not their names. What are they called?"

"What!" replied the doctor. "In your circles, in which I scarcely venture, you've never heard of the Count and Countess Serlon of Savigny as a fabulous model of conjugal love?"

"Upon my word, no," I said. "One speaks rarely of conjugal love in the company I keep, doctor."

"Hmm, hmm, quite possibly," said the doctor, answering his own thoughts more than mine.

"In such a world, which also happen to be theirs, many things occur that are more or less correct. Yet in addition to their having a reason not to keep such company, they live almost the whole year through in the old Castle of Savigny in Cotentin. Such rumors once circulated about them, all the way to the district of Saint-Germain – where a certain solidarity among the nobility persists – that one would prefer to keep quiet than to talk about them."

"And what were these rumors, then? Ah, now you've interested me, doctor! You must know something about them. The Castle of Savigny is not far from the city of V., where you were once a physician."

"Now, about these rumors," said the doctor, pensively taking a pinch of tobacco. "Well then, one thought them to be false! All this is in the past ... And yet, although a marriage of inclination and the joys it brings remain the provincial ideal among all romantic and virtuous family mothers, they were not able – at least those whom I knew – to talk their daughters out of this one!"

"Nevertheless, doctor, you say that Philemon and Baucis ..."

"Baucis, Baucis, harrumph, my dear sir," interrupted Dr. Torty, violently passing his finger over the entire hooked length of his parrot nose (one of his gestures). "Do you not find that this girl has less of a Baucis air to her than an air of Lady Macbeth?"

"Doctor, my dear and lovely doctor," I said again, my voice filled with tender caress, "are you going to tell me what you know of the Count and Countess of Savigny?"

"The physician is the confessor of modern times," said the doctor with a solemn tone of quiet irony. "He has replaced the priest, my dear sir, and is bound to the selfsame confessional secrecy."

He looked at me maliciously because he knew my respect and love for the objects of Catholicism, of which he was the enemy. He blinked his eyes; he thought that he had stopped me.

"And he will remain bound to it, just like the priest!" he added dramatically with his most cynical laughter. "Come over here, we are going to have a little chat."

Reader Comments