The Body Snatcher

Tuesday, February 9, 2016 at 09:47

Tuesday, February 9, 2016 at 09:47  It might be better to pretend that this story never happened, which of course it did. Graverobbers are for obvious reasons of supply some of history's most chronicled criminals, yet with the explosion of medical science in the mid-nineteenth century, it was not graves which were violated but the bodies themselves. These bodies were sold in parts to anatomists and medical students for scientific purposes and tomb after tomb went hollow. Even more morbid is the fact that demand began to get fussier and fresher bodies became all the rage, leading one particular team to pursue the freshest bodies out there, those of the still living. The actions of William Burke and his accomplice were so notorious as to be immortalized in a verb, so when we meet Fettes and Macfarlane in this small masterpiece of horror, we understand them to be his direct descendants.

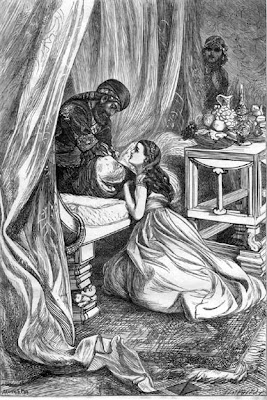

It might be better to pretend that this story never happened, which of course it did. Graverobbers are for obvious reasons of supply some of history's most chronicled criminals, yet with the explosion of medical science in the mid-nineteenth century, it was not graves which were violated but the bodies themselves. These bodies were sold in parts to anatomists and medical students for scientific purposes and tomb after tomb went hollow. Even more morbid is the fact that demand began to get fussier and fresher bodies became all the rage, leading one particular team to pursue the freshest bodies out there, those of the still living. The actions of William Burke and his accomplice were so notorious as to be immortalized in a verb, so when we meet Fettes and Macfarlane in this small masterpiece of horror, we understand them to be his direct descendants.The story begins with their unwanted reunion: Fettes is constantly soused and impecunious; Macfarlane, garbed in the finest boutique-bought whitewash, a successful London physician. They meet by chance and are none too pleased about it, for their consciences share crimes of diabolical scheming. It turns out both were once students of a certain K., a physician who collected cadavers for his own medical experiments, and had no qualms or questions about the work of his minions. The tale is too brief to provide much characterization of their sinister master, so we only get the following snippet:

There was at that period, a certain extramural teacher of anatomy, whom I shall designate by the letter K. His name was subsequently too well known. The man who bore it skulked through the streets of Edinburgh in disguise, while the mob that applauded at the execution of Burke called loudly for the blood of his employer. But Mr. K- was then at the top of his vogue; he enjoyed a popularity due partly to his own talent and address, partly to the incapacity of his rival, the university professor. The students, at least, swore by his name, and Fettes believed himself, and was believed by others, to have laid the foundations of success when he had acquired the favour of this meteorically famous man.That K. is really Stevenson’s compatriot Robert Knox is not so much a secret as a literary device to prevent the piece from becoming historical journalism. Suffice it to say that imagining two of Knox’s suppliers, with a few pale strokes of ghoulish vengeance thrown in for good measure, would make a glorious tale of horror (not unlike what would be produced half a century later in a very different setting). Stevenson’s genius does not allow him, however, to stop at the Gothic. The arc of such a story (devised and perfected by, among others, this author) is built in five acts: the re-encounter, the origin of their acquaintance, an “agenbite of inwit,” the appearance of an even greater evil, and then the destiny of all souls involved. You might think the opening section clumsy and almost unconnected to the meat of the tale, and you would not be wrong. But the story makes us wait for the integrant appearance of a man called Gray.

Gray is a marvelous sketch in the annals of literature, a being that barely defiles more than two pages and yet is etched deep in our memory. He becomes, I can say without being indiscreet, the unremovable stain. These are all evildoers, but there is something about him that outhowls the other devils:

This was a small man, very pale and dark, with coal–black eyes. The cut of his features gave a promise of intellect and refinement which was but feebly realised in his manners, for he proved, upon a nearer acquaintance, coarse, vulgar, stupid. He exercised, however, a very remarkable control over Macfarlane; issued orders like the Great Bashaw; became inflamed at the least discussion or delay, and commented rudely on the servility with which he was obeyed. This most offensive person took a fancy to Fettes on the spot, plied him with drinks, and honoured him with unusual confidences on his past career. If a tenth part of what he confessed were true, he was a very loathsome rogue; and the lad’s vanity was tickled by the attention of so experienced a man.The end looms the moment Macfarlane is obliged to foot the bill for their long and gluttonous night, and then spend the next day “squiring the intolerable Gray from tavern to tavern.” This all culminates in a scene in a carriage that could be taken (substituting a car or train for the fly) from any contemporary horror film. If you haven’t read Stevenson, you are missing one of literature’s unheralded giants, capable of portraying both sides of human nature in equal load (as he does in a more famous work, one of the most perfect literary creations of all time). In The Body Snatcher, there is only one side, and it is remarkably vile; but its vileness wields the distinct advantage of making us cringe in fear of dark and darting shapes in the night. Endless, blackest night, that is.