The Norwood Builder

Friday, August 15, 2008 at 13:38

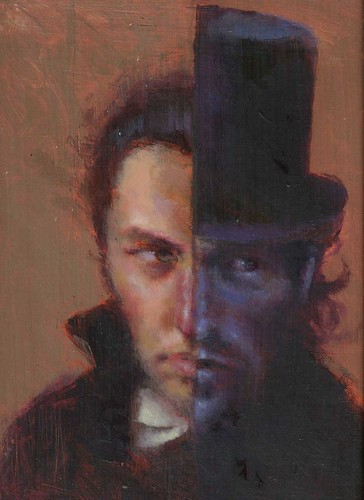

Friday, August 15, 2008 at 13:38 Were you to review modern cinema's development of the thriller, you would come across a singularly ingenious topos called the "framing of an innocent fugitive." Ingenious in that it often involves a situation in which the opinion of the world is so vehemently opposed to considering the fugitive's innocence that he himself thinks he might have committed some wrongdoing in an altered state. Once upon a time we had demons; now we have drugs, hallucinations or mental illness, but the lack of responsibility or blackout periods remain (indeed, sleepwalking was one of the least satisfying ways of explaining gaps in memory, and is featured as the solution in more than a few prominent nineteenth-century crime novels). There are, of course, other methods for handling the subject, including the possibility that a mandarin plot is afoot. This is the worst fate of all, because the conspirator is near-omnipotent and, if truly diabolical, wise to any moves that you might undertake. Such is the conundrum facing John Hector MacFarlane, a young solicitor who seeks advice and refuge in this story.

Being green and unobtrusive, MacFarlane cannot overcome his amazement when a well-to-do fellow bachelor, Mr. Jonas Oldacre, approaches him in his office one day and asks him to cast his last will and testament "into proper legal shape." The fifty-two-year-old builder is a verbal stranger to MacFarlane, although the cantankerous Oldacre was at one time acquainted with MacFarlane's parents. Papers are examined, hands are shaken, and the young man promises to come by Oldacre's house the following night to examine some scrip and housing deeds. Yet that is not all: the sole benefactor of the will is none other than MacFarlane himself, a condition justified by the relationless Oldacre's having known his family and wanting to reward a "very deserving young man." MacFarlane proceeds to the builder's estate, staffed only with a housekeeper, and discusses the terms of the will before suspiciously open French windows and a suspiciously open safe. The examination of the paperwork takes much longer than expected, forcing the young solicitor to pass the night in a nearby inn. The next morning, by his own account, he learns that Oldacre's estate was damaged severely in a fire that had begun the night before, and that Oldacre himself perished in the inferno. All of which makes the young MacFarlane a very wealthy and, unfortunately, very wanted man.

Being green and unobtrusive, MacFarlane cannot overcome his amazement when a well-to-do fellow bachelor, Mr. Jonas Oldacre, approaches him in his office one day and asks him to cast his last will and testament "into proper legal shape." The fifty-two-year-old builder is a verbal stranger to MacFarlane, although the cantankerous Oldacre was at one time acquainted with MacFarlane's parents. Papers are examined, hands are shaken, and the young man promises to come by Oldacre's house the following night to examine some scrip and housing deeds. Yet that is not all: the sole benefactor of the will is none other than MacFarlane himself, a condition justified by the relationless Oldacre's having known his family and wanting to reward a "very deserving young man." MacFarlane proceeds to the builder's estate, staffed only with a housekeeper, and discusses the terms of the will before suspiciously open French windows and a suspiciously open safe. The examination of the paperwork takes much longer than expected, forcing the young solicitor to pass the night in a nearby inn. The next morning, by his own account, he learns that Oldacre's estate was damaged severely in a fire that had begun the night before, and that Oldacre himself perished in the inferno. All of which makes the young MacFarlane a very wealthy and, unfortunately, very wanted man.

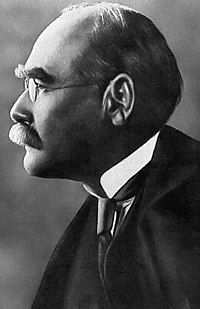

Surely, one might snicker at this "filthy wealth of coincidence" (to use this author's expression); yet upon reflection of most any important event in one's life a plethora of hitherto unnoticed data may surface. This is a very modern phenomenon. Our advances in forensics have enabled us to construct situations in which we can identify the culprit from processing all the evidence on hand, regardless of the personality, motives, or relations of the people involved. Indeed, it is really with the introduction of Holmes and Watson – two men of science – that we begin to do away with what is specifically called Menschenkenntnis in German, or a "knowledge of human nature" (the fact that we have no exact term for it should be explanation enough). While I applaud any progress made in the field of identifying or verifying criminal perpetrators, one should not forget that these persons, while desperate, ignorant or evil, are still just like the rest of us, that is, motivated by very personal issues and factors that can be grandly categorized but not fully understood without an understanding of how people tend or tend not to do things. When Holmes became world-famous at the end of the nineteenth century, he was praised by scientific pundits who saw him as a paladin against the Romantic notions of human behavior. Here was a man who thrived on proving things by testing every physical detail against every other; whose creator and sidekick were both medical doctors; and who shunned theories that encapsulated superstitions, curses, or other unprovable agencies. But what many forget is that Conan Doyle himself believed in all these forces, and spent the greater part of his life promoting their importance. Was this a natural recoiling from Holmes's massive shadow? Was it owing to his realization that he would forever be known as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the great Sherlock Holmes?

Perhaps, although unlikely. Despite Holmes's empiricist methods, he is a wise knower of men. He understands the little details that might turn an otherwise pleasant human being into a criminal, and re-imagines this evolution at its every stage. As for poor MacFarlane, a preponderance of proof lies against him: he was the last visitor to see Oldacre; his fingerprints are on the primary documents as well as all over the house; he had no connection to Oldacre, having just met him, and was relatively impecunious and living with his parents; and, of course, he stood to inherit a heaping pile of banknotes as a result of this crime. And while a new piece of physical evidence cements the police's case, Holmes plows on owing to a hunch that has nothing to do with all the daggers he sees before him. But it does have to do with that most despicable of human fallacies, the unwillingness to forgive, the opposite of all we should strive for. And for grudges there is rarely any physical evidence.