Lik

Wednesday, April 20, 2016 at 11:22

Wednesday, April 20, 2016 at 11:22 I suppose I do not quite understand those who are fascinated by comets and craters yet cannot believe in the immortality of the human soul. Now there are many, many shades of my ignorance, to be conquered by my future selves or to be left untouched in some dark corners of this universe; but my lack of understanding has more to do with aim than with substance. To wit, why do we bother? Why be kind to each other if kindness is but a façade for advantage? Why love when all love's labor will be lost? Why laugh or cry when all events and emotions are time, that cruelest of tyrants, simply spotting us treats? Some particularly smug proponents of the five senses' predominance have labeled those who think we are better than fossils and fuels "history deniers." These are the same megaphoning militants who tell us that we should not believe anything that cannot be verified – as if any of history can be "verified" – and we will leave them to their morons, oxy or otherwise. I do not deny history because I believe in moral justice; I, on the contrary, reinforce it. Of all things, natural selection is supposed to adhere so strictly to predetermined laws – laws announced to all, in other words – as to make the determinants of those laws likewise predetermined. (This chain goes back in time to something, one might guess, indeterminate; but the megaphoners claim that's when everything exploded into determinism; better to calm them down before in their red-faced rants they, too, explode.) Nevertheless, we should not limit natural selection to the chameleon or the slowly rising primate. Human souls also have a destiny plotted well in advance by their valor and fortitude, which brings us to a story in this collection.

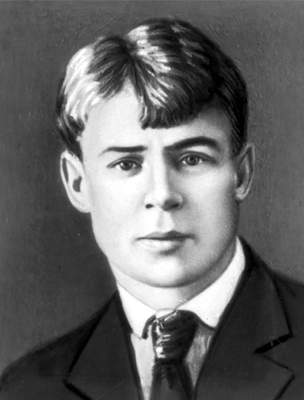

Our Lik, an acronym for his Christian name Lavrentiy Ivanovich Kruzhevnitsyn, is a humble beast, but one relatively well-evolved. He is an actor by the sheer fact that this profession is the only one which brings him any form of intercourse with the world, much less any income. As we meet him, he is consigned to a minor role in an "ideally idiotic" French drama of the conventional family-conflict-honor mould. The drama is in French, and Lik speaks the language with exactly the suitable Russian swallowing of vowels and stress to imbue the play, appropriately called The Abyss, with the proper dash of foreign flavor. He also begins to understand the role as his sole reality, suggesting that he is not so much an actor as a person bereft of true identity:

Our Lik, an acronym for his Christian name Lavrentiy Ivanovich Kruzhevnitsyn, is a humble beast, but one relatively well-evolved. He is an actor by the sheer fact that this profession is the only one which brings him any form of intercourse with the world, much less any income. As we meet him, he is consigned to a minor role in an "ideally idiotic" French drama of the conventional family-conflict-honor mould. The drama is in French, and Lik speaks the language with exactly the suitable Russian swallowing of vowels and stress to imbue the play, appropriately called The Abyss, with the proper dash of foreign flavor. He also begins to understand the role as his sole reality, suggesting that he is not so much an actor as a person bereft of true identity:

It was hard to say, though, whether Lik (the word means "countenance" in Russian and Middle English) possessed genuine theatrical talent or was a man of many indistinct callings who had chosen one of them at random but could just as well have been a painter, jeweler, or ratcatcher. Such a person resembles a room with a number of different doors, among which there is perhaps one that does lead straight into some great garden, into the moonlit depths of a marvelous human night, where the soul discovers the treasure intended for it alone.

On the subject of choice, there are few passages in the English language of greater lucidity or beauty. Lik may not have an outward appearance of genius, but then again most persons who seem at first glance to fit that profile turn out to be blustering frauds. What Lik does possess, however, is the inscrutable sense of himself that accompanies a sensitive soul; he could be an artist of any caliber – an organ grinder, a balalaika player, a street mime – but how he views the world makes him a first-class aesthete. He is most afflicted by what has always tortured the artist – time and its undertow, and the vastness of eternity lapping its waves upon the minute skeleton half-buried on a sandy beach:

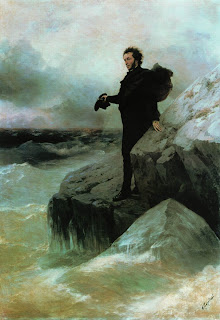

The proximity of the sea, whose presence he divined beyond the lemon grove, oppressed him, as if this ample viscously glistening space, with only a membrane of moonlight stretched tight across its surface, was akin to the equally taut vessel of his drumming heart, and, like it, was agonizingly bare, with nothing to separate it from the sky, from the shuffling of human feet and the unbearable pressure of the music playing in a nearby bar.

We also learn that Lik is terminally ill, a coincidence that befits a far lesser work of literature – but there are, as it were, no coincidences in the works of Nabokov. Lik will carry on down his lonely path until a palaver with a fellow lodger reveals an element of our actor's past that we might have suspected all along. And that element is Oleg Petrovich Koldunov.

Koldunov is both Lik's relative and nemesis, one thought long dead. We cannot say too much about Oleg Petrovich, who reenters his miserable cousin's life almost twenty years after he left it, because Koldunov bludgeons us with monologue after monologue, often, it seems, arguing with himself or a past version of Lik. In fact, Koldunov is as loquacious and irritating as Lik is quiet and non-offensive (Lik's "absence from friendly gatherings, instead of being attributed to a lack of sociability .... simply went unnoticed"). There are moments in the narrative's second half when we cannot believe in Oleg Petrovich. That is to say, we don't believe in him as a human being at any point ("it was perfectly obvious he was an idler, a drunk, and a boor"); but soon enough we don't even believe in him as a fictional character. He is so exaggerated and incensed that we get the distinct impression that he might simply be a figment of a very neurotic actor's mind. The few alleged facts we do gather may strangely apply to both him and his cousin:

Why has life systematically baited me? Why have I been assigned the part of some kind of miserable scoundrel who is spat on by everybody, gypped, bullied, thrown into jail? Here's an example for you: When they were taking me away after a certain incident in Lyon .... you know what they did? They stuck a little hook right here in the live flesh of my neck .... and off the cop led me to the police station, and I floated along like a sleepwalker, because every additional motion made me black out with pain. Well, can you explain why they don't do this to other people and then, all of a sudden, do it to me? Why did my first wife run off with a Circassian? Why did seven people nearly beat me to death in Antwerp in '32 in a small room?

There are other hints strewn amidst the story's increasingly odd second part that allow one to think, if for but a few paragraphs, that we are dealing with a single human soul engaged in internal debate. I am happy to say, however, that this impression is thoroughly demolished by our final scene. Or is it? Do white shoes betoken more than summertime and posh eccentricity? Should we be concerned that since Lik "had accumulated no spiritual treasures, [he] was hardly an interesting prey" for the looming Scythe? Hardly interesting at all.