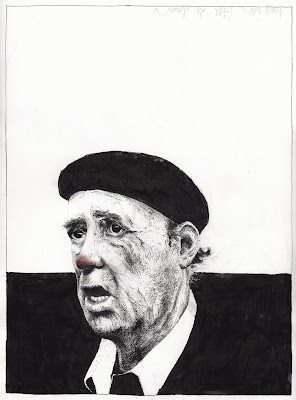

The following speech against German reunification was given by this late author on February 2, 1990. “Landless journeymen” (Vaterlandslose Gesellen, usually as a plural) was one of the ways in which the last Kaiser would refer to anyone of the political left, as well as a general term for cosmopolitan businessmen who fancy personal profit over their country’s needs. The speech is included in this book.

As I was coming from Göttingen shortly before Christmas, and just as I had wanted to change trains to Lübeck at Hamburg’s central train station, a young man came up to me. He stopped me dead in my tracks, called me a traitor, and left me with this word echoing. Then, after I had casually purchased a newspaper, he came up to me again, now not with mild threats but openly proclaiming that the time had come to get rid of people like me. I shook off this annoyance while still on the platform and proceeded to Lübeck wrapped in my thoughts. “Traitor!” A word that, coupled with “landless journeyman,” was truly part of German history. Was the truculent young man not right after all? Can a fatherland for whose benefit one is to get rid of people like myself not remain something stolen from me? This is indeed the case. Not only do I fear a simplified Germany as the composite of two Germanys, I also reject a unified state and would be relieved – be it owing to German prudence or to the objection of our neighbors – if it never came to pass.

As I was coming from Göttingen shortly before Christmas, and just as I had wanted to change trains to Lübeck at Hamburg’s central train station, a young man came up to me. He stopped me dead in my tracks, called me a traitor, and left me with this word echoing. Then, after I had casually purchased a newspaper, he came up to me again, now not with mild threats but openly proclaiming that the time had come to get rid of people like me. I shook off this annoyance while still on the platform and proceeded to Lübeck wrapped in my thoughts. “Traitor!” A word that, coupled with “landless journeyman,” was truly part of German history. Was the truculent young man not right after all? Can a fatherland for whose benefit one is to get rid of people like myself not remain something stolen from me? This is indeed the case. Not only do I fear a simplified Germany as the composite of two Germanys, I also reject a unified state and would be relieved – be it owing to German prudence or to the objection of our neighbors – if it never came to pass.

Of course, I am well aware that my stance currently unleashes debate if not aggression, which doesn’t only make me think of the young man at Hamburg’s central train station. Much subtler and tidier work is being done by the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung with those people who categorically refer to themselves as left-wing intellectuals. It is not enough for their editors that communism is bankrupt; democratic socialism, including Dubček’s dream of socialism with a human face, is also finished. One thing that capitalists and communists have always had in common is the preventive condemnation of a Third Way. That’s why any reference to the now-contested autonomy of the GDR and its citizens is immediately greeted with emigration and resettlement figures. The self-confidence that they developed despite suffering under oppression for forty years, and which ultimately became revolutionary, is now written in fine print. So we are supposed to get the impression that in Leipzig and Dresden, in Rostock and East Berlin, it is not the people of the GDR who have triumphed but the whole gamut of Western capitalism. And the pillaging has already begun. Hardly had one ideology lost its hold before another ideology stepped in as if it had always been there. If necessary, market economy instruments of torture are flashed. Who doesn’t feel it gets nothing. Not even bananas.

No, I do not want an improper, crowing, attack-battened fatherland like that, even if nothing is at my disposal to ward off mockery apart from my own thoughts. I already fear that reunification, regardless of what name it chooses to camouflage itself, is inevitable. The strong Deutschmark will see to that; the mountainous printed editions of Springer’s media empire, now in collaboration with Rudolf Augstein’s Monday morning meanderings, will see to that; and German forgetfulness will see to that. In the end, we’ll number about eighty million. Once again we will be one, we will be strong. And even when we try to speak softly, we will be heard in the loudest tones. Finally, because enough is never enough, we will manage with our tough Deutschmark and recognition of Poland’s western border to subjugate economically a good chunk of Silesia, a good chunk of Pomerania, and, in textbook German fashion, once again isolate ourselves and strike fear in the hearts of others. I am already betraying this fatherland. My fatherland would have to be more varied, brighter, more neighborly, wiser from the damage done, and much more palatable to Europe.

Nightmare versus dream. What is preventing us from helping the German Democratic Republic and its citizens by means of just and long overdue burden sharing, so that the GDR might strengthen itself economically and democratically and its citizens might make less of an effort to remain at home? Why must the German Federation, whose neighbors could come to accept us, always keep adding titles to its name, from espousing a vague Paulskirche concept as a federal state to assuming the form of a large federal republic? Are comprehensive unity, greater land area, conglomerated economic power then all desired components of growth? Isn’t all this once again too much? Since the mid-1960s, I have given speeches and written essays against reunification and spoken out in favor of a confederation. Here again I will answer the German question. I’ll sum it up in not ten, but five points:

First: A German confederation abolishes the postwar relationship of the two German states as foreign countries. It also removes a worthless border separating Europe while still taking into consideration the concerns and fears of its neighbors by constitutionally doing without the need to reunify the two states.

Second: A confederation of both German states would not do any harm to either postwar German history or the history of either of the two states. In fact, it would enable something new: independent commonality. And a confederation is sufficiently sovereign to meet all federal obligations as well as those of mutual European security.

Third: A confederation of both German states is more suited to the process of European unification than an overweight unified state, all the more since a unified Europe will be a confederation and will have to overcome traditional national statehood.

Fourth: A confederation of both German states starts us on the path to a different and desirably new understanding of ourselves. It bears a collective responsibility to German history as a nation of culture. This understanding of nation was taken up by the failed Paulskirche convention, and is to be seen as an expanded concept of culture joining the variety of German culture without a need to declare German national unity.

And Fifth: A confederation of both German states, as a resolution to a conflict between states of a nation of culture, would give impetus to the worldwide resolution of different yet comparable conflicts, be it in Korea, Ireland, Cyprus, or the Near East, anywhere, in fact, where national state action has set aggressive borders or where it seeks to widen them. Resolution of the German question through confederation could serve as an example.

A few additional comments: the German unified state only existed in its enlarged size for seventy-five years: as a German Reich under Prussian dominion; as the doomed Weimar Republic; and, up until its unconditional surrender, as the Greater German Reich. We should be conscious – our neighbors are quite conscious – of how much suffering this unified state has caused and the level of misfortune it has brought upon itself and others. The genocide that can be made relative in no way and is summarized in the word Auschwitz remains on the conscience of this unified state. Never had Germans, in all their history until that point, fallen into such ill repute. They were neither better nor worse than other peoples. Complex-saturated megalomania did not lead Germans to make use of this opportunity as a nation of culture within a federal state, but to thrust upon themselves with all force the title of unified Reich. This was the early prerequisite for Auschwitz. Latent, as well as common anti-Semitism then became the basis of its power. The German unified state abetted the National Socialist racist ideology by providing a repulsively suitable foundation. Nothing will get past this acknowledgement. Whoever thinks of Germany now and looks for answers to the German question must think of Auschwitz as well. The site of horror as an example for the lingering trauma excludes the possibility of a future unified German state. Should it, as I fear, nevertheless be attempted, it will be doomed to failure from the onset.

More than twenty years ago here in Tutzing the phrase “transformation through rapprochement” was coined; a long since controversial but ultimately verified formula. Rapprochement is now part of everyday politics. The German Democratic Republic was transformed thanks to the revolutionary will of its people; but as its citizens look on – half in admiration, half in condescension – the Federal Republic of Germany has yet to be transformed. “We don’t want,” they say to their Eastern counterparts, “to tell you what to do, but…” And interference is now common. Help, real help will only come under West German conditions. Property sure enough, but please no property of the people. The western ideology of capitalism which seeks to obliterate every other ideological ismus speaks up like a pistol held to the head: either a market economy or…

And who wouldn’t raise his hand here and give in to the blessings of the strong, whose impropriety is so clearly made relative by its success? I fear that we Germans will also turn down a second chance at self-determination. Being a nation of culture with confederated variety is obviously too little for us. And “rapprochement through transformation” is, if only because of its exorbitance, simply asking too much. But the German question cannot be answered in Marks and Pfennigs.

What did the young man at Hamburg’s central train station say? Right he was. As the case may be, I am counted among the landless journeymen.

Friday, July 3, 2015 at 23:17

Friday, July 3, 2015 at 23:17  It is possible that some will sympathize with my plight, yet such is not my feeling. My small business so fills me with worry and concern that my temples and forehead ache. I do not even have the satisfaction of believing that this will improve, for my business is truly small. For hours in advance I am obliged to meet certain stipulations, possess a butler's memory, avoid terrible mistakes, and in one season calculate the fashions and tastes of the subsequent season. These are not, mind you, the tastes that would predominate among people like me, but among those inaccessible populations of the countryside.

It is possible that some will sympathize with my plight, yet such is not my feeling. My small business so fills me with worry and concern that my temples and forehead ache. I do not even have the satisfaction of believing that this will improve, for my business is truly small. For hours in advance I am obliged to meet certain stipulations, possess a butler's memory, avoid terrible mistakes, and in one season calculate the fashions and tastes of the subsequent season. These are not, mind you, the tastes that would predominate among people like me, but among those inaccessible populations of the countryside.