Certified Copy

Monday, August 10, 2015 at 22:31

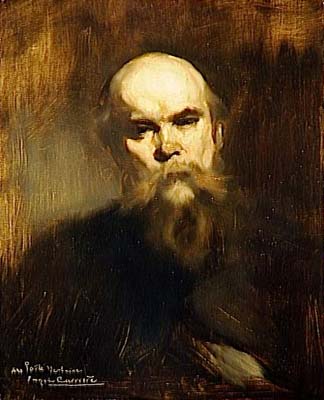

Monday, August 10, 2015 at 22:31 We begin this film with an Italian book on display before a plain gray wall. The book is entitled Copia conforme, and its companions are an unmanned table, an unmanned microphone, a dirty chimney, and the aura of an imminent press conference. This is indeed what occurs. A man with some resemblance to this Italian-American director addresses us (we still cannot see the audience) in Italian about a British scholar with the plain name of James Miller, whose apparent tardiness "cannot be excused because of the traffic since his room is upstairs." Miller appears at last, to a small group, about forty people, most of whom are women. At this talk, conducted in English, Miller makes almost the same joke as his predecessor but says he "walked here." He also comments perfunctorily on the weather because Italians would expect no less of an Anglo-Saxon. Then he takes a swipe at the literary taste of his fellow Englishmen and we understand that his book, which won "best international essay of the year," has been a limited success. In fact, "limited success" may be the best caption for James Miller (William Shimell).

Suave-looking, if considerably more attractive from far than from up close, Miller quickly decides he has already lost his audience and begins luxuriating in pseudophilosophical mumbo-jumbo ("It is difficult to write about art: there are no fixed points of reference, there are no immutable truths"). As he is about to deliver a prepared statement in Italian thanking Marco Lenzi – the man who introduced him and translated his book – a woman comes and sits in one of the two front row seats marked riservato (Lenzi took the first one), and is shot a look by Lenzi that acknowledges the decorum of such an act. We do not know this at the time, but this may be the film's most important moment since it safely excludes one interpretation that the plot will come to suggest. Soon thereafter a young boy of maybe twelve enters the room and begins to bug the woman (Juliette Binoche), who is very obviously his mother. The boy will spend a long time looking over at his mother, who jokes with Lenzi and pendulates from subrisive attention to Miller to fiddling with her handbag in that unique way a woman has of signaling her boredom.

Suave-looking, if considerably more attractive from far than from up close, Miller quickly decides he has already lost his audience and begins luxuriating in pseudophilosophical mumbo-jumbo ("It is difficult to write about art: there are no fixed points of reference, there are no immutable truths"). As he is about to deliver a prepared statement in Italian thanking Marco Lenzi – the man who introduced him and translated his book – a woman comes and sits in one of the two front row seats marked riservato (Lenzi took the first one), and is shot a look by Lenzi that acknowledges the decorum of such an act. We do not know this at the time, but this may be the film's most important moment since it safely excludes one interpretation that the plot will come to suggest. Soon thereafter a young boy of maybe twelve enters the room and begins to bug the woman (Juliette Binoche), who is very obviously his mother. The boy will spend a long time looking over at his mother, who jokes with Lenzi and pendulates from subrisive attention to Miller to fiddling with her handbag in that unique way a woman has of signaling her boredom.

In the meantime, Miller drones on about "the authenticity of art" (a tired modern topos): he mentions the origin of the word 'origin' (the Latin orīrī, 'to arise, be born'); compares our art productions to us since we are "DNA replicas of our forebears"; and underscores that certifying the authenticity of the work of great artists in all epochs and disciplines has become a most important vocation – and I think you get the idea. But when our pontificating expert lists the four criteria by which a work of art can be certified, the woman is beckoned to leave the room by her son, which she does, all the while looking back in mocking amusement at our speaker. In a marvelous twist, Miller has only listed two criteria ("the form and shape of the artefact"; "the material of which it is made") when the presentation is interrupted by a cell phone's ring – Miller's phone – that he actually answers. We shift scenes and see the woman outside in the Tuscan streets walking several yards in front of her son, who barely looks up from his handheld game console. They sit down for a cheeseburger and the son, still not looking up, asks her casually how many of Miller's books she bought. "Six," she replies, as if the number held some significance. The interrogation continues in that vein that drives teenagers crazy, to wit, when they know that their parents are hiding something from them and won't divulge it – precisely what teenagers do all day to their parents, but anyway. The woman states she will give a copy to a friend, her son protests that the friend already has it, and she mentions an "autographed copy" (exemplaire dédicacé) as her aim. Then the son knows that she simply wants to see the fellow again and calls her on it. She does not deny the charge, and we have our plot.

With Lanzi's help Miller visits the woman in her underground store, very much a Roman catacomb replete with busts and other antiques. Something bothers him about this place – perhaps simply that it so resembles a crypt – so he spurns her repeated offer to remain there and ejects both of them into "the fresh air." "Your invitation," he reminds her, "said nothing about an antiques shop." She is visibly upset by this whole sequence, strangely reminiscent of a man's failed attempt to keep a desired woman in what he believes is his irresistible bachelor pad, but which to her seems very much like a trap. They then set off on one of those surreal drives so popular in the work of some directors (Kiarostami is no exception) where certain peculiar aspects of the two interlocutors will be revealed. From this first isolated exchange we can deduce one thing (a few other things will be deduced later on): the woman, who is never named, is not trying to impress Miller by allowing him to prattle on about aesthetics; she is trying to become his muse. Every time he speaks abstractly, she slips him a concrete example, usually something simpler and more grounded. She accuses him of trying to prove the unprovable not to nettle him but to see whether he might indeed listen and come down to earth next to her. Of course, he rebuts such accusations soundly and consistently. "I'm afraid," he says with the tone of an emergency room surgeon breaking some bad news, "there's nothing very simple about being simple." This implies that it is harder for someone of impeccable taste to debase himself with everyday culture than for someone ensconced in that same mundane rubbish to be elevated towards the sublime, an argument in favor of art's transformative power upon the human soul. Miller then promises her his favorite joke, whose punchline about a soda bottle she guesses and which, anyway, is so insipid we truly hope that his calling it his "favorite joke" was the real attempt at humor (his sour reaction suggests it wasn't). They arrive in a small town renowned for weddings, young couples, and a painting that was once thought to date to Roman times then exposed fifty years ago as an eighteenth-century forgery, and somehow we sense that although Miller has a train at nine that night, we will not be leaving that small town any time soon.

It is here as well that the film begins to hint at another plot, at the resemblance of this nameless woman's son to this bleary-eyed Englishman, at the consequences of raising a family, at the omission of the son's surname in the dedication of that autographed tome. Is the son a "certified copy" of the father? Are we witnessing a long-suffering married couple fallen out of love? The indentured servitude to a one-night-stand that bequeathed a child? Two people having fun while playing fantasy roles that have no kinship with their realities? The rest of the film predicates this unusual indeterminacy, yet the first fifteen minutes of Certified Copy ensure only one plausible explanation to its subsequent events, which will not be revealed here. Suffice it to say that those who love ambiguity may love this film, even if there is no real ambiguity at all – that is, unless the characters are asylum-ripe. The broad boilerplate notions of art are belied by the petty, private hell, or facsimile of a petty, private hell, unleashed by its second half, which, we suppose, is meant to show how little aesthetic theory has to do with life or art. Many internet sources indicate some professional actors were considered for the role of Miller (Shimell is no stranger to the limelight being a well-known opera singer, but is not a trained actor), which would have made the whole affair incredibly pretentious and melodramatic. As it is, the balance is perfect: Binoche, who flutters among English, French, and Italian at a hummingbird's pace, maintains her mildly histrionic posturings; whereas Shimell must simply find a way to handle them without the ease of someone long accustomed to disguise. The result is that we come to think that the woman is not being truthful and that Miller, for all his ridiculous aphorisms (the most quoted will surely be from a "Persian poem" he supposedly happens to know), may be the victim of a harridan's whims. Towards the dead center of the film, a supporting character detects that husband and wife are indeed seated in her café and offers some well-meant advice about what makes a man tick ("Men need work: it distracts them and we can lead our lives"; "It can't be all that bad if your only complaint is that your husband works too much"; "When there's no other woman we begin to see work as our rival") and we believe her because old women, especially old women in movies, tend to be conduits of the truth. And what about what happened five years ago near the replica of a famous statue? After all, without that revelation in Florence, there would have been no original to copy.