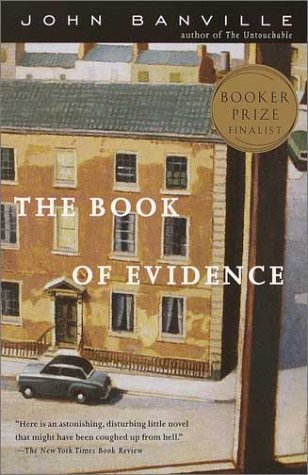

The Book of Evidence

Friday, June 27, 2008 at 00:40

Friday, June 27, 2008 at 00:40

There is an unfortunate subgenre of popular fiction which can simply be labeled “the confessions of a killer.” Even unaided by cable or other lurid purveyors of societal atrocities, an attentive observer would find many such works in any bookstore servicing the whims of the demos. We are intrigued by such stuff, if only for a moment, because we are naturally attracted to evil. Not because we are inherently evil ourselves — we are, I say boldly, nothing of the kind — but because bad things show us the counterpoise to normalcy that stirs our juices with the potential knowledge of why there is so much vileness in our world. This is why the more morbid or unrepentant the culprits, the more galling and demented the crimes, the more revolting the violence, the faster the chill that races up our spines as we lurch closer to Old Nick himself. These diabolists ratiocinate at each step of their miserable life, from the most fundamental of daily tasks to love, death, and betrayal. Everything has a cause, effect and logical framework; everything is the fault of others who conspire against them to bring out their very worst; every line, every feature, every shadow spreads like an inkwell across the virgin white page; and what they did is simply the unerring mathematical consequence of these factors. Yet the true indication of a master stylist is not what to include, but what to omit; and no, every last detail does not need to be fanned into a Chinese lantern. Which brings us to the jailbird confessions of Freddie Montgomery, the insufferable protagonist of this novel.

There is an unfortunate subgenre of popular fiction which can simply be labeled “the confessions of a killer.” Even unaided by cable or other lurid purveyors of societal atrocities, an attentive observer would find many such works in any bookstore servicing the whims of the demos. We are intrigued by such stuff, if only for a moment, because we are naturally attracted to evil. Not because we are inherently evil ourselves — we are, I say boldly, nothing of the kind — but because bad things show us the counterpoise to normalcy that stirs our juices with the potential knowledge of why there is so much vileness in our world. This is why the more morbid or unrepentant the culprits, the more galling and demented the crimes, the more revolting the violence, the faster the chill that races up our spines as we lurch closer to Old Nick himself. These diabolists ratiocinate at each step of their miserable life, from the most fundamental of daily tasks to love, death, and betrayal. Everything has a cause, effect and logical framework; everything is the fault of others who conspire against them to bring out their very worst; every line, every feature, every shadow spreads like an inkwell across the virgin white page; and what they did is simply the unerring mathematical consequence of these factors. Yet the true indication of a master stylist is not what to include, but what to omit; and no, every last detail does not need to be fanned into a Chinese lantern. Which brings us to the jailbird confessions of Freddie Montgomery, the insufferable protagonist of this novel.

Our book is divided in halves. There is first and predictably a long introduction to a crime whose gory details are suggested in asides and semi−demented philosophizing. Our man Freddie is not an original thinker, nor, one should add, does he have any pretensions in that general direction. He is “amazed at the blue innocence of the sea and sky.” His morals are nonexistent, but so is his lucidity of thought. It is in the sweat−stained journal of a degenerate teenager that we may expect comments on “the bad in its inert, neutral, self−sustaining state,” a fallacy in reasoning so basic that its mention begets only shudders and headshaking. He has a wife, Daphne, a son, and two parents all painted in the most grotesque colors, each description increasingly exaggerated, momentum caused by the excitement of stringing together macabre observations. Yet occasionally these suicidal rantings swirl into a divine wind:

I thought how strange it was to be here like this, glass in hand, in the silence and calm of a summer evening, while there was so much darkness in my heart. I turned and looked up at the house. It seemed to be flying swiftly against the sky. I wanted my share of this richness, this gilded ease. From the depths of the room a pair of eyes looks out, dark, calm, unseeing.

This is the mood throughout: bouts of insuppressible guilt interrupted only by noticing that he has been bleeding for the last thirty minutes. That Freddie has killed, or the identity of his victim, which is not immediately obvious, should not interest us as much as the descent of his soul into absolute darkness. I suppose we are to be enthralled by this cultured person (he is a proponent and student of statistics and probability theory), fallen and forlorn. I suppose as well that the freak gallery that pervades the world of Freddie Montgomery — a man possessing “an inveterate yearning towards backgrounds” so as to avoid his reality’s loathsome foreground — must be seen as they are described, as an acting troupe of clowns and charlatans, drunks and dyspeptics. And I also suppose that Freddie and his moral warts are to be forgiven long enough for us to be aware of how much everything has changed, and how, how, how this could happen to anyone at all.

But we are not aware. We are not aware because despite the backcover blurbs, Banville’s intention is nothing of the kind. He seeks first and foremost, like all good writers, a collation of pleasing detail in an atmosphere of his choosing. That is why we shuttle between Spain, a country Freddie despises once his wife and son are left as hostages, and Merrie England, where the native Irishman also does not seem to belong. It is only when Freddie describes what he truly loves (this Irish port being one of those things) that Banville’s carbons crystalize into a diamond:

In the ten years since I had last been here something had happened, something had befallen the place. Whole streets were gone, the houses torn out and replaced by frightening blocks of steel and black glass. An old square where Daphne and I lived for a while had been razed and made into a vast, cindered car−park. I saw a church for sale — a church, for sale! Oh, something dreadful had happened. The very air itself seemed damaged. Despite the late hour a faint glow of daylight lingered, dense, dust−laden, like the haze after an explosion, or a great conflagration. People in the streets had the shocked look of survivors, they seemed not to walk but reel. I got down from the bus and picked my way among them with lowered gaze, afraid I might see horrors.

You will find motifs and motives in this painting, as well as in a certain bombing that may be the handiwork of a politically violent faction, but this passage alone justifies Freddie’s lapsarian musings and outshines every other moment in the novel. So you shouldn’t necessarily believe Freddie when he claims his life has no moments, just the “ceaseless, slow, demented drift of things.” His crime has neither passion nor meaning, which we cannot say about the starry sky above his darkened cell.

deeblog |

deeblog |  2 Comments |

2 Comments |  Banville in

Banville in  Book reviews,

Book reviews,  English literature and film

English literature and film