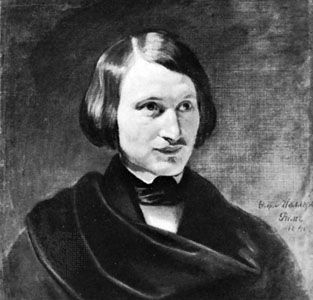

Nikolai Gogol

Wednesday, March 5, 2008 at 23:35

Wednesday, March 5, 2008 at 23:35 Writer: You have an accent in English. Are you from Europe?Whether such an exchange ever occurred (the joke has the bitter flavor of truth) is not as interesting as the context. Contempt for Ukrainian literature and the concept of Ukraine as a cultural and political entity independent of both Poland and Russia is still widespread, owing largely to its lack of famous men and women of letters. Although the founder of the modern language was a poet and artist whose balding head, handlebar moustache, and resigned chin (to the fate of his native tongue, some would say) are engraved into numerous monuments worldwide, his existence is practically unacknowledged outside Slavic departments. Even in those hallowed halls enthusiasts tend, after Russian, to study Polish, Czech, Serbian, and Bulgarian before knitting their brows at the oddities of the Ukrainian alphabet, Cyrillic with a sprinkling of one–eyes and two–eyes. Most Ukrainian writers, history regrets to inform us, chose other mediums in which to express themselves. And none was weirder and more brilliant than this small dainty man, the subject of one of the English language's most succulent literary biographies.

Ukrainian: I’m from Ukraine.

Writer: From Urania? [walks away]

Symbolism with him [Gogol] took on a physiological aspect, in this case optical. The mutterings of passers–by were again symbolic, this time an auditory effect which was meant to render the hectic loneliness of a poor man in an opulent crowd. Gogol, and Gogol alone, spoke to himself as he walked, but the monologue was echoed and multiplied by the shadows of his mind. Passing as it were through Gogol’s temperament, St. Petersburg acquired a reputation of strangeness which it kept up for almost a century, losing it when it ceased to be the capital of an empire.This is very much the oddness of Petersburg that pervades Russian literature from Pushkin to Bely, the incongruity of traditional European architecture and customs against the thoughts and rapturous originality of its natives. I have not been to Petersburg in a few years, but little has changed. Thirty years passed between Nabokov’s last spring in his hometown and the passage above, which, fifty years later felt like it had been culled from the evening edition of Argumenty i fakty. The point is that Gogol, and Gogol alone, changed Russian literature both for its creators and its admirers, domestic and otherwise. With the possible exception of Pushkin, he is more responsible than any author for how Slavic literary scholars have evaluated the last two hundred years.

He did not, however, come about this brilliance by living the simple and successful life of an academically–minded writer who spends days in a library and nights behind his desk. A soft, effeminate man, Gogol was completely impractical in mind and body: he was constantly impecunious, ill, or both; he loved to fib and exaggerate because, like all great writers, fiction was far richer than the worries of a mortal; he listened to no one but himself, fled from creditors and would–be benefactors alike, and traveled alone and aimlessly in Europe for years as if trying to absorb its culture by sponging its streets with his boots. The results were few (Gogol would die, we are told immediately, in his early forties after an abortive leeching cure) but magnificent and his modest corpus is still studied with avidity by Russianists everywhere. Nabokov demolishes some previous attempts at rendering Gogol’s eccentric prose (so badly, in fact, that I don’t think any publisher would have ever hired these poor dead souls ever again) and supplies his own passages, which display his own mastery and wit and swell and ebb with the same unmistakable rhythm of Nabokov’s discursive writings. All of which, I may add, could probably not be written any more clearly or concisely, nor with more passion and understanding for his subject.

He did not, however, come about this brilliance by living the simple and successful life of an academically–minded writer who spends days in a library and nights behind his desk. A soft, effeminate man, Gogol was completely impractical in mind and body: he was constantly impecunious, ill, or both; he loved to fib and exaggerate because, like all great writers, fiction was far richer than the worries of a mortal; he listened to no one but himself, fled from creditors and would–be benefactors alike, and traveled alone and aimlessly in Europe for years as if trying to absorb its culture by sponging its streets with his boots. The results were few (Gogol would die, we are told immediately, in his early forties after an abortive leeching cure) but magnificent and his modest corpus is still studied with avidity by Russianists everywhere. Nabokov demolishes some previous attempts at rendering Gogol’s eccentric prose (so badly, in fact, that I don’t think any publisher would have ever hired these poor dead souls ever again) and supplies his own passages, which display his own mastery and wit and swell and ebb with the same unmistakable rhythm of Nabokov’s discursive writings. All of which, I may add, could probably not be written any more clearly or concisely, nor with more passion and understanding for his subject.Yet Gogol’s most significant contribution may well be his obsession with a rather untranslatable word, poshlost’, about which Nabokov digresses for over twenty pages. Poshlost’ has no precise English synonym (the German Kitsch is probably the closest, although this latter is strictly speaking an aesthetic term), but might be explained as the "the belief in or propagation of superficial, sentimental and populist values as true culture." Examples would be pop and paparazzi shows and magazines or any Hollywood love or war story, but with a modicum of discipline these can be ignored. Much more egregious offenders are books which might portray an earnest young man who, in an effort to "make it in the world," befriends some multicultural characters, falls in love with sunsets, dogs and soft jazz, repeats to himself that life is really not about the pursuit of material wealth — although he doesn't quite convince the reader of that — and, at the end of his "journey," metaphorically envisions humanity's fate in the hands of the scattered few around him. Most books, as it were, fall into this disreputable category. The word itself is in very common usage in modern Russian, and has come to signify the unshakeable twitch that surfaces upon hearing or seeing something so absolutely false and so infuriatingly pandering to common thought and common happiness that even pacifists like myself want to smack someone in the vicinity. To Russians' great credit, the word is extremely old and consistently applied; and to Gogol’s credit, he is in every way the opposite of it, just like Tomas is a “monster in the kingdom of kitsch” in this novel.

And to Nabokov’s credit, he restrains himself for the most part from overtaking his beloved forerunner. Yes, it is Nabokov’s show; but if you are familiar with his work, you know that he cannot share a stage to save his life and that his imprint is indelibly left on everything he touches. He even has time to tell us about his deepest fears:

In his Dikanka and Taras Bulba phase .... Gogol was skirting a very dreadful precipice. He almost became the writer of Ukrainian folklore tales and ‘colorful romances.’ We must thank fate (and the author’s thirst for universal fame) for his not having turned to the Ukrainian dialect as a medium of expression, because then he would have been lost. When I want a good nightmare I imagine Gogol penning in Little Russian dialect volume after volume of Dikanka and Mirgorod stuff about ghosts haunting the banks of the Dneipr, burlesque Jews and dashing Cossacks.