The Fugitive

Sunday, June 25, 2017 at 14:03

Sunday, June 25, 2017 at 14:03 We have heard so often the story of the innocent man framed that it has become less of a fictional cliché and more of a reminder of our own first disobedience. Such a scenario is carved into the underpinnings of our nightmares, of how life can be snatched up and mutilated beyond recognition (some critics would love to emphasize our own repressed guilt in these instances, but most people's guilt is manifest and petty). What could be worse than being accused and convicted of a crime one did not commit? Loving the victim of that crime and knowing the true culprit perhaps, which brings us to this masterful film.

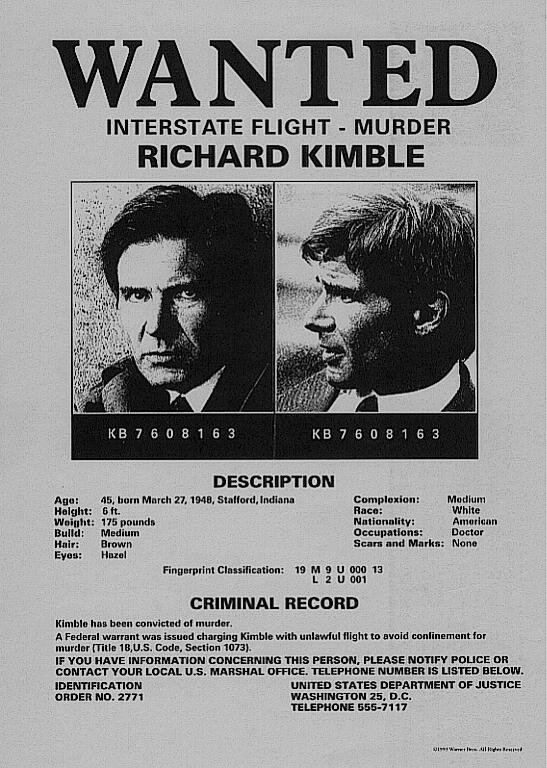

We know the accused will be Chicago physician Richard Kimble (a still-spry Harrison Ford). Kimble has everything that an average soul could want: he is cultured, financially successful, kind-hearted, attractive, and married to a ravishing beauty appropriately named Helen (Sela Ward); in other words, for the conventions of tragedy, he fits the bill quite well. We would not feel any sympathy towards a person of his privileges if he lost little, or if the person in question had nothing to lose at all. It is therefore appalling to watch our poor doctor enter his lovely home late one evening and find Helen bludgeoned and bloody beside a frightful-looking character (Andreas Katsulas), who in the ensuing tussle is revealed to have only one arm. One supposes it is important to have Kimble ostensibly exculpated from the very beginning so as to increase his pathos, although it hardly remains beyond plot twists to have had him order a killing anonymously. This latter option seems less likely when a filthy wealth of evidence, including life insurance benefits, points towards only one man. Kimble is arrested, tried, and sentenced to die by lethal injection with great alacrity, precisely because the sequence seems like a dream whose details could not possibly coincide with the real world. Throughout the entire proceedings Kimble retains a look of costive disbelief reflecting what he thinks of human justice; and as a man of science, he must know that law and its derivative vocations are as flawed and prone to misinterpretation as any lab test or vial. That he decides to operate outside the law is somewhat owing to happenstance: traveling on one of those prison buses that always seem to provoke mayhem, an aborted escape by another prisoner gives him his freedom − if being a hunted death row fugitive in a Chicago winter can be somehow considered liberty.

We know the accused will be Chicago physician Richard Kimble (a still-spry Harrison Ford). Kimble has everything that an average soul could want: he is cultured, financially successful, kind-hearted, attractive, and married to a ravishing beauty appropriately named Helen (Sela Ward); in other words, for the conventions of tragedy, he fits the bill quite well. We would not feel any sympathy towards a person of his privileges if he lost little, or if the person in question had nothing to lose at all. It is therefore appalling to watch our poor doctor enter his lovely home late one evening and find Helen bludgeoned and bloody beside a frightful-looking character (Andreas Katsulas), who in the ensuing tussle is revealed to have only one arm. One supposes it is important to have Kimble ostensibly exculpated from the very beginning so as to increase his pathos, although it hardly remains beyond plot twists to have had him order a killing anonymously. This latter option seems less likely when a filthy wealth of evidence, including life insurance benefits, points towards only one man. Kimble is arrested, tried, and sentenced to die by lethal injection with great alacrity, precisely because the sequence seems like a dream whose details could not possibly coincide with the real world. Throughout the entire proceedings Kimble retains a look of costive disbelief reflecting what he thinks of human justice; and as a man of science, he must know that law and its derivative vocations are as flawed and prone to misinterpretation as any lab test or vial. That he decides to operate outside the law is somewhat owing to happenstance: traveling on one of those prison buses that always seem to provoke mayhem, an aborted escape by another prisoner gives him his freedom − if being a hunted death row fugitive in a Chicago winter can be somehow considered liberty.

On Kimble's trail comes the eminently cocksure U.S. Marshal Sam Gerard (Tommy Lee Jones at his very best), who as a film character will resemble an artful codger or two from our own existence. Jones at the time of filming was in his mid-forties, four years younger than Ford. Yet his demeanor is distinctly one of a much older man who has seen and done everything necessary to prove that he is always right. Gerard does have less hair and more wrinkles than his co-star, as well as much less of a need to be in top running condition, but this palpable difference in generations extends into the strategies employed. Being an inveterate rule-follower, Gerard assumes that all success feeds off discipline, this deduction being especially applicable to a man devoted to the rules of nature and medicine. While police procedurals will regularly contrast those who think inside the box and those for whom volatile shapes would be the only means of caging their inventions, Gerard is not mistaken. What he simply does not understand, however, is the degree of indignation that Kimble feels (never mind that he spends most of the film under the presumption that Kimble was rightfully incarcerated). Why he does not know the greater limits of human emotion is not touched upon by the script; perhaps he has never been married or lost a loved one; perhaps he has always managed to treat life's vicissitudes as the function of his decision-making. At times we sense that Gerard would hardly be above gunning down his quarry at the slightest violation of his methods.

This fundamental ignorance generates the tension required to elevate The Fugitive from the typical feline-rodent event to something grand and unnerving. The film has been compared by some critics to opera, and the comparison stands. The frost-ridden forests and icy pathways imbue the setting with a certain Wagnerian appeal, and the film's unusual length, often cited as its only flaw, actually aids in our concept of time: we cannot glance at our watches and estimate the next shootout, or even whether that shootout will ever occur. This lack of predictability coupled with Gerard's scene-stealing presence suggest that while we suspect Kimble will be ultimately acquitted, we cannot be assured that it will happen while he is still alive. As opera, we have a great hero, a terrible and earth-shattering crime, an unknown villain (one-armed men usually do not make good kingpins), and an ambiguous character who may act in the service of evil while attempting to do good − or exactly the reverse. There are many nice touches to the film, including a much-lauded vignette in which Kimble's Hippocratic oath trumps his own will to survive, but a few questions persist. Doesn't Kimble's flight argue culpability? Was it necessary to kill Helen when Kimble could easily have been out of town for business reasons? Couldn't there be a less conspicuous person to carry out an assassination than someone utilizing a state-of-the-art and not inexpensive prosthetic limb? Not that we are given too many chances to catch our breath and ponder such trivialities.

Reader Comments