The Rescue Artist

Tuesday, October 22, 2013 at 13:55

Tuesday, October 22, 2013 at 13:55 In our languorous days of globalization, a movement into a planet that will not be uniform so much as on allegedly equal footing, one may wonder why the theft of art has become increasingly popular. Is it because everything now has a price tag, as if there were no object worth contemplating for its beauty and mystery alone? Or does knowing something about art mean having good taste? Without refuting either one of these cynicisms, one should remember not to place the art before the course – that is to say, good taste will necessarily involve a knowledge of our most brilliant and sublime creations. Now it may be overmuch to ask our government to spend millions to protect our artistic treasures when it could be earmarking that same sum to ensure the safety of our citizens. After all, who but the most self-indulgent aesthete would claim that saving a painting is more important than saving a human life? A point strategically omitted in this well-known book.

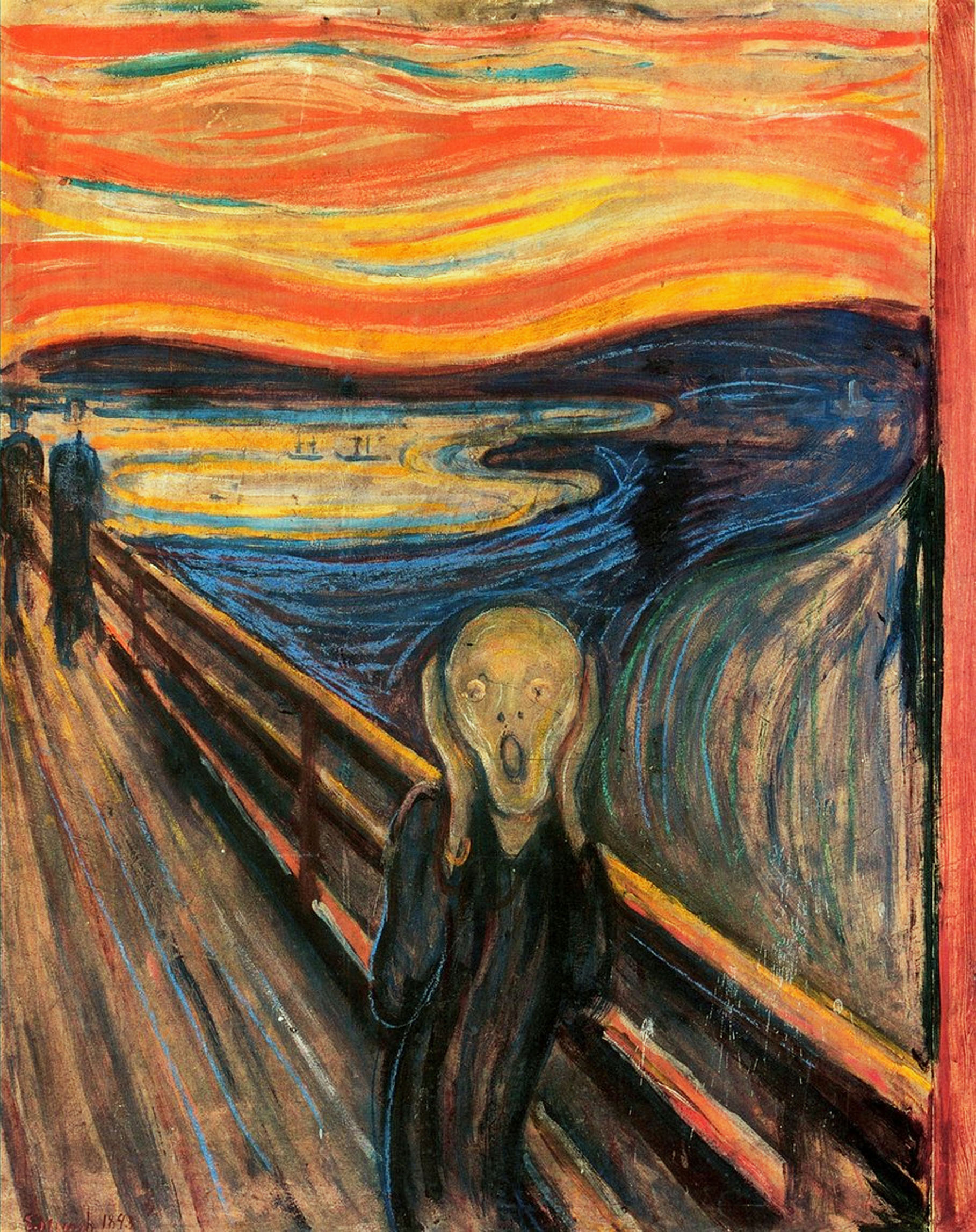

The crime was shocking, yet hardly unprecedented. Painted when the city was still called Kristiania, one of the most heralded works of European symbolism or expressionism or something or other was stolen almost effortlessly from an Oslo museum on the eve of this event. There is rampant hypothesis, in both this book and the sources it collects, that the action was planned as something anti-establishment – a somewhat mistaken point to which I will return. What can be said is the following: On February 12, 1994, two men shimmied up a ladder and into a museum window, then exited about a minute closer to daybreak by the same means, leaving the ladder in its very compromising position. One filched getaway car was exchanged for another, and by the time the Lillehammer Olympics were about to begin all of Norway was infected by scandal. An Italian or Dutch work from centuries past would not have been nearly as painful. No, this was ostensibly the most famous painting by Norway's most acclaimed artist, and one that had already become an icon equally in popular culture and among those of fine taste. Edvard Munch's "Scream" was gone, and the police was as clueless as the reader staring wildly at his newspaper's headline. A hero is needed, a hero who will brave all dangers and hoodlums to regain one of Norway's national treasures and one of the most influential paintings in world history. And that hero is an Anglo-American detective by the name of Charley Hill.

The crime was shocking, yet hardly unprecedented. Painted when the city was still called Kristiania, one of the most heralded works of European symbolism or expressionism or something or other was stolen almost effortlessly from an Oslo museum on the eve of this event. There is rampant hypothesis, in both this book and the sources it collects, that the action was planned as something anti-establishment – a somewhat mistaken point to which I will return. What can be said is the following: On February 12, 1994, two men shimmied up a ladder and into a museum window, then exited about a minute closer to daybreak by the same means, leaving the ladder in its very compromising position. One filched getaway car was exchanged for another, and by the time the Lillehammer Olympics were about to begin all of Norway was infected by scandal. An Italian or Dutch work from centuries past would not have been nearly as painful. No, this was ostensibly the most famous painting by Norway's most acclaimed artist, and one that had already become an icon equally in popular culture and among those of fine taste. Edvard Munch's "Scream" was gone, and the police was as clueless as the reader staring wildly at his newspaper's headline. A hero is needed, a hero who will brave all dangers and hoodlums to regain one of Norway's national treasures and one of the most influential paintings in world history. And that hero is an Anglo-American detective by the name of Charley Hill.

We learn much, almost too much, about Hill, but the book is called The Rescue Artist for a reason. Hill comes to Norway after a checkered career in just about every field he chose except the retrieval of stolen works of art. His American father was a career serviceman, his British mother a dancer, and Hill bears both lineages in addition to being a stout casuist. He fought in Vietnam, pounded a beat for Scotland Yard, and all the while talked back to every superior he had, not because of a lack of social skills but owing to his realization that any type of fettered, scripted existence would contradict the very chirpings of his soul. Bureaucrats, Hill's mortal foes, are nothing more than "whingeing, plodding, paint-by-number dullards," which explains his attraction to crime. It would have been easy to romanticize the roughs who steal paintings to trade them for money, drugs, or arms. But author Edward Dolnick does nothing of the sort. Using Hill and his aliases as a prism, Dolnick endeavors to peel open the lid on art theft (even though he claims police involvement of the kind enjoyed by Hill in his heyday is a thing of the past) through a survey of some of the more infamous twentieth-century thefts. The large country manor appears as the obvious target, as does the moneyed nobleman too doddering or indifferent to count his masterpieces every last morning. There is one amazing story about a French waiter and his mother's highly lamentable actions which I will not spoil, as well as a number of interesting factoids such as the ban in Luxembourg on undercover police operations, a clear legacy of the Second World War. We also learn a few things about the particularly striking work of this Dutch master, about Munch's life and motives (larded, alas, with speculative psychobabble), and a few other bits of information that will serve the careful reader quite well at his next cocktail party. Through it all our constant is Hill, who tries his best to come off as a refined gentleman but who really does possess all the characteristics of his underworld antagonists except the unwieldy conscience.

Which brings me to the matter as to why paintings and suchlike are stolen in the first place. Dolnick has a concept of art that is distinctly that of the non-artist. On two separate occasions, Dolnick uses cartoon characters as references to people's physical appearance; and while his catachresis does not extend into malapropism (one night in May is "winter," the next day is a late-arriving "spring"), his imagery and metaphors are often decidedly mixed. Perhaps, given the time line, he was a bit worried that his story might not be nearly as exciting as he had first hoped. Amidst this brand of forced journalese we find some magnificent observations ("Duddin's world and the conventional one are not self-contained. They meet occasionally, as the lion's world sometimes meets the antelope's"; "He is, after all, a lone wolf, not a creature made to work in harness"; "No heavy lifting, except for the occasional glass of wine at a fundraiser"; "Physical courage turned out to be just a fact, like being six feet tall or having brown hair"), and Dolnick's perspective on why The Scream was lifted when it was suggests concord with Hill's much-belabored non-conformist attitudes towards, well, just about everything. Yet Hill's portrayal as an eccentric could not really be farther from the truth. As it were, the combination of a short temper, thuggery, competitiveness, intellectual capacity, and a taste for adventure all describe a certain type of man who in another lifetime might have been an explorer, but in our days is usually a sea captain. A more revealing question would be: when does a thief want publicity? Perhaps when he's afraid that no one really cares about what he has stolen.

Reader Comments