The Nose (part 1)

Monday, October 10, 2011 at 16:56

Monday, October 10, 2011 at 16:56 The first part of a story by this Russian writer. You can read the original here.

I.

On March 25th in St. Petersburg an extraordinarily strange occurrence took place. The barber Ivan Yakovlevich (his surname has been lost; even his placard featuring a sudsy-cheeked gentleman with the inscription "And there will be blood" has nothing more), residing on Voznesenski Avenue, the barber Ivan Yakovlevich awakened rather early and detected the smell of hot bread. Sitting up a bit in his bed he saw that his wife, an utterly honorable woman who loved to drink coffee, was removing just-baked breads from the oven.

On March 25th in St. Petersburg an extraordinarily strange occurrence took place. The barber Ivan Yakovlevich (his surname has been lost; even his placard featuring a sudsy-cheeked gentleman with the inscription "And there will be blood" has nothing more), residing on Voznesenski Avenue, the barber Ivan Yakovlevich awakened rather early and detected the smell of hot bread. Sitting up a bit in his bed he saw that his wife, an utterly honorable woman who loved to drink coffee, was removing just-baked breads from the oven.

"Today, Praskovya Osipovna, I won't be having coffee," said Ivan Yakovlevich. "Instead, I would like a hot bun with onion."

(That is to say, Ivan Yakovlevich would have liked to have both, yet knew it was fairly impossible to demand two things at once as Praskovya Osipovna really did not like such megrims). "Let the fool eat bread; all the better for me," thought his wife to herself. "There'll be an extra serving of coffee." And she tossed a bun on the table.

For propriety's sake Ivan Yakovlevich put on coattails over his shirt and, having sat down at the table, sprinkled some salt, prepared two heads of onion, and took up a knife in his hands. Then he made a knowing face and set to cutting his bread. Having cut the bread in two halves, he looked at the center and espied something white. Ivan Yakovlevich prodded it carefully with his knife then groped it with his finger. "Solid!" he said to himself. "What could it be?"

He stuck his fingers in and pulled out – a nose! Ivan Yakovlevich let his hands fall; rubbing his eyes, he began to grope the object. Indeed, it was a nose! It seemed to him somewhat familiar – and Ivan Yakovlevich's face was suddenly filled with horror. But this horror was nothing compared to the indignation that came over his wife.

"Where did you cut off that nose, you pig?!" began her wrath. "Swindler! Drunkard! I'm going to report you to the police personally, you thieving swine! I already heard from three people that you fiddle so extensively when you shave your customers that their noses can barely stay on!"

But Ivan Yakovlevich was neither alive nor dead. He realized the owner of the nose was none other than the collegial assessor Kovalev, whom he shaved every Wednesday and Sunday.

"Hold on, Praskovya Osipovna! I'll just wrap it in a handkerchief and place it in the corner. Let's let it lie there a wee while, and then I'll take it back."

"Absolutely not! So that I can have a sliced-off nose sitting around my house? You blubbery worm! A worm, I might add, who only knows how to sling his blade around and in no way ever fulfills his duties, you idling, amoral lump! So that I defend you to the police? Now that is some twaddle, you filthy rat! Begone with it! Begone! Remove it anywhere you please, as long as I do not have to inhale its fumes!"

Ivan Yakovlevich was still standing there as if dead. He thought and thought and still didn't know what to think.

"Who the devil knows how this happened!" he said at length, scratching behind his ear. "At this point I probably couldn't tell you whether I came home drunk yesterday. But impossible events must befall all objects, because bread is a baked item and noses most certainly are not! I just can't figure it out!"

Ivan Yakovlevich fell silent. The thought of the police searching him for the nose and then accusing him made him completely numb. He imagined now the scarlet collar, handsomely lined in silver, the sword, and his whole body trembled. He soon found his underwear and shoes, threw on this ragged heap, and, accompanied by Praskovya Osipovna's unmild remonstrances, tucked the nose into a handkerchief and went out onto the street.

He wanted to stash it under something, beneath the curbside stone by the gates, for example, or accidentally drop it somewhere then hasten down an alley. Alas, he immediately bumped into an acquaintance who began with that terrible question, "Where are you off to?" and Ivan Yakovlevich could not get away for even a minute. His second time around he actually managed the drop, but a distant sentry waved his halberd and beseeched: "You dropped something! Pick it up!" And Ivan Yakovlevich had to retrieve the nose and return it to his pocket. Despair prevailed upon him, all the more as the pedestrians incessantly multiplied and stores and shops pushed open their shutters.

He opted to head for Saint Isaac's bridge – couldn't he at least manage to toss it in the Neva? ... And here I'm afraid I am somewhat guilty, as I have said nothing about Ivan Yakovlevich, an honorable man in many respects.

Ivan Yakovlevich, like every honest, decent Russian workman, was a stupendous boozehound. And although every day he shaved the chins and cheeks of others, his own jaw remained forever unshaven. Ivan Yakovlevich's tail coat (Ivan Yakovlevich never wore a frock coat) was piebald; that is to say, it was black with grey and brownish-yellow clouds. His collar was glossy, and instead of three buttons only threads hovered. Ivan Yakovlevich was also a remarkable cynic, and when collegiate assessor Kovalev would habitually inform him during the shave, "Your hands, Ivan Yakovlevich, always smell!" – Ivan Yakovlevich would answer "Now why would they smell?" "I don't know, friend, but they smell," the collegiate assessor would reply. And having snorted some tobacco, Ivan Yakovlevich would lather him for that on his cheeks, under his nose, behind his ears and below his beard – in a word, wherever he jolly well desired.

Now this honorable citizen had already reached Saint Isaac's bridge. First, he took a quick look around; then he leaned over the railing as if he were looking under the bridge to see whether there weren't some fish splashing about – and the handkerchief and nose were surreptitiously tossed. He felt as if he had just shed ten poods! Ivan Yakovlevich even laughed! And instead of shaving bureaucrat chins he headed for an institution by the name of "Food and tea" (so read the sign) to order himself a glass of punch, when suddenly at the far end of the bridge he noticed a housing inspector of aristocratic appearance sporting a sword, broad sideburns and a triangular hat. Ivan Yakovlevich went numb; just then the housing inspector wagged his finger at him and said:

"Come hither, my dear sir!"

Knowing the procedure, Ivan Yakovlevich removed his hat even though he was still far away, swiftly approached the inspector, and then said:

"To your health, your lordship!"

"No, no, my good sir, no lordship. Tell me now, what you were you doing standing out there on the bridge?"

"I swear, sir, I was on my way to shave, but I simply wanted to see whether the fish weren't bustling about."

"Lies, lies! You won't get out of it that easily! Kindly answer the question!"

"I am prepared, your grace, to shave you twice even three times a week, without the slightest objection," answered Ivan Yakovlevich.

"Sheer poppycock, friend! Poppycock, you hear me? I already have three barbers shaving me and they all deem it a great honor. Now kindly explain what you were doing on that bridge!"

Ivan Yakovlevich grew very pale ... And here a fog engulfs our events, and about what happened next nothing more is known.

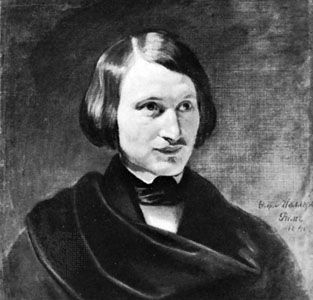

Gogol in

Gogol in  Russian literature and film,

Russian literature and film,  Translation

Translation