There is a style no longer in circulation among our literary works because we no longer wish to merge with eternity. We have come to entertain notions of a beyond as an unknowable consequence of very knowable processes, and the inevitable outcome of billions of years of inevitable outcomes. In principio erat verbum, et verbum erat apud Deum, et Deus erat verbum all sounds very nice, but now we have moved past God – and sometimes it seems like He has returned the favor – and into the much more tenable field of hard science. Our verbs (or words, as verba means both) bestowed upon us by a benevolent Creator who willed the universe into shape have been evicted from their cozy domiciles and replaced with volatile and complicated droids owing their allegiance solely to the latest whims of the latest wizards. These wizards would advise me – if I ever bothered listening to them instead of just humming a happy tune whose melody I cannot quite explain – that our life is simply a collection of detail and we are simply collectors. The best observers are those who leave no stone unturned, no star unnamed, no fossil uncarbondated, and no deity unblasphemed. Come now, ignoramus, who could be smarter than we are? After all, we've almost got everything figured out except where we came from and where we go, if anywhere. All the intermediary steps, however, are as crystal clear as the ice on the planet billions of miles away that we can make out at times but which has to exist because, unlike our eyes, our machines are manmade and can be trusted to the ultimate degree. When has our reason ever failed us? Only, I suppose, all those centuries as conspiring sacerdotal agents blinded us, piling up lie after lie so that we remain enslaved to their evil and all-encompassing plan. Yet we have finally broken free. Now when we gaze upon nature's contours, all we see is a composite of data, molecules, light particles, atoms, quarks, and the potpourri and whatever other blandishments time has coaxed out of that endless and unswerving metal rod, evolution. With this fact now happily proven, let us rejoice and examine this superb novel.

The site of our novel's events is a place near the border of two large, powerful and mysterious countries. One of them has since crumbled beneath the falsehoods of its imposed doctrines; the other, once party to those same doctrines, has growled and beaten its chest and moved on to the much more justifiable plan of unbridled capitalism, albeit with a few political restrictions. And as is appropriate given the host country's dimensions, the titular invitation involves fifteen dignitaries from around our lonely planet, a motley assortment of men of power: two preachers from Harlem, one of whom turns out to be an actor; another American who scribbles indignant notes as the speakers hold forth; a priest from the local church who serves as a sort of co-host; military representatives from more than one country; a Russian, "the Nero of cinema," now a naturalized subject of the British queen; and the ostensible master of ceremonies, a man "with the massive head of a mountain dweller." What they talk about is, apart from the occasional aside, never expressed directly; instead, they are described in detail which the average reader will find intolerable. Take, for example, the approach to the invitation site:

Now the procession of heavy cars preceded by the police car crossed through the town (and the town rose from the steppe, whose language was once Chinese, then Chinese transcribed in Latin characters, then Chinese transcribed into Cyrillic characters; where without counting a good twenty languages – languages of the sons of camel drivers, of Mongol horsemen, of inhabitants descended from those monstrous mountains, of caravaning Tartars, Afghans, Kyrgyz, Turkmens, Uzbeks, ancient slaves, newly arrived peoples ... there was even, the interpreter said, a German colony – two official languages were now spoken, both in Cyrillic characters) which sixty years ago had been nothing more than a simple village (or maybe not even that: a stopover, a point at the end of the endless steppes and before the passage to those terrifying mountains) and which now had a population of almost one million people of all races.

Those races are then qualified, and followed by other links in a chain of qualifications which extends through many pages and an incredible range of sensory perceptions. We are dealing with the repetitions and surfaces of a very particular brand of writing, one that came about and shook its readers shortly after the Second World War and which has lost some of its reputation by virtue of our readily shrinking attention spans. True enough, without a brilliant architect behind its towers the nouveau roman can become a dreary exercise in concatenation; at its best, however, it is as close as literature can get to painting its own picture. No image exists without the wealth of otherness in its vicinity; and no person can be an island unto himself without the tidal wave of sensation from the millions of other living beings breathing his air and distracting him from the solipsistic extremes to which, we are told, he is naturally prone.

As opposed to other proponents within the movement (with the notable exception of this recently deceased French writer, its greatest representative), Simon is much more cohesive and allegorical than one would first imagine. Yes, his world is fractured along the aleatory whims of association, proximity and pure chance. But from among these pieces he fashions an alternative reality that is richer than that of his contemporaries or, for that matter, the silly ramblings of so many modern writers who eschew plot in favor of an old shoebox of scattered observations that are neither interesting nor artistic. On every page Simon's artistry prevents him from slipping into such easy victories of style. His parenthetical commentary (the second word of the novel is already trapped within its bubble) often supersedes the plain text before and after it, and we come to see that it is the circumjacent detail that outranks the prime focus. Even a funeral can seem fragmented along the numerous storylines that it obliges to intersect:

(... the bust of the new General Secretary now cut off by the parapet at the top of the cube of red marble at that place where, before him, so many old men were kept, surrounded by the highest dignitaries with, to his immediate left, looking at him, a man with a fur hat atop a pensive face, devastated, akin perhaps to an old and tired wolf (maybe not old exactly, just devastated; maybe not interested, just pensive), whereas the new General Secretary had his head uncovered, with his baldness, his surprisingly young almost doll-like features, scrutinized and evaluated by millions of men, women, diplomats, journalists, and creators of theories) ... and now, seated at the end of that table which so resembled the table of some dull administrative board of some joint stock company or perhaps didn't, or that of an international bank or perhaps not that of an international bank, with its tray waxed like a mirror, its glasses and bottles of mineral water, in that room of bare walls without a single portrait, neither of his predecessors nor of him.

There is so much to admire about this passage and countless others, all perfectly waxed and reflecting each and every other page like a perverse hall of mirrors. Simon is read less than he should be precisely because we have grown allergic to longer paragraphs (such as the book-long masterpieces of this Austrian writer) and prefer our literature like our scotch: neat and plain. But then again, the truth is rarely as neat or plain as we might hope.

Sunday, January 4, 2009 at 16:57

Sunday, January 4, 2009 at 16:57  Fatigued by hospice bed and incense foul

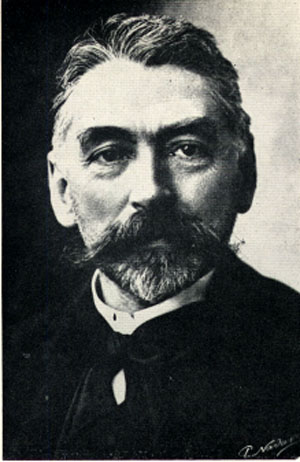

Fatigued by hospice bed and incense foul  Mallarmé in

Mallarmé in  French literature and film,

French literature and film,  Poems,

Poems,  Translation

Translation