Blow Out

Thursday, October 22, 2015 at 08:04

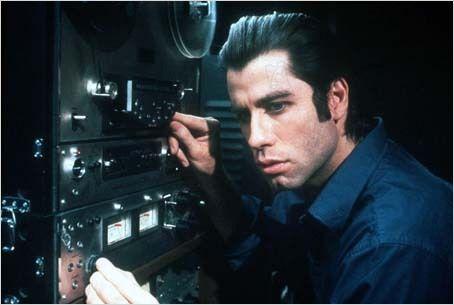

Thursday, October 22, 2015 at 08:04 Given the implausible frenzy of this film’s opening, we should not be surprised that its conclusion is underpinned by a notion of affection only teenage sensibilities (and perhaps a few disturbed Romantic poets) could concoct. But between these uncomely bookends we are treated to sensational filmmaking, at once highly derivative and highly original, proving again that old adage about achieving maximum originality by following a model. The model is noir, the Man Who Knew Just Enough to get himself embroiled in a maelstrom of deadly currents, or, as it were, deadly current events. And our doomed sailor is an unambitious sound man by the name of Jack Terry (John Travolta).

Our time is the late 1970s and our place a Philadelphia that some may mistily remember, but one about to celebrate a non-existent holiday, Liberty Day. The insertion of this fictitious fête is significant, because it lends the entire film a certain unreality that abets its game of twisted perceptions. And these perceptions begin and end in the rather terrible little studio that employs Jack Terry. Jack exudes intelligence in a very humble way, ostensibly in line with his self-description as "the guy who always put together radios as a kid, always won science fairs ... you know the type." He is also young, handsome, and almost suspiciously genuine, which means he must inevitably be sheltering a memory of great embarrassment or regret. He will reveal that regret much later in our film, in a passably convincing scene that also explains why he has relegated himself to the orchestration of slag-ridden grindhouse. I say "passably" because considering how much thought was put into making Blow Out, the motive behind Jack's series of unfortunate acts of kindness and interference will strike the viewer as plucked from a rather dusty hat. What acts of kindness, you ask? Well, what would the average citizen do if he saw, on a dark and lonely night on a dark and lonely park bridge, a car skid off the road into a lake? But since Jack Terry has been out all that evening recording nature's music for his sonic arsenal, he will have something more to do once he has fished the requisite damsel in distress (Nancy Allen) out of the drink.

Our time is the late 1970s and our place a Philadelphia that some may mistily remember, but one about to celebrate a non-existent holiday, Liberty Day. The insertion of this fictitious fête is significant, because it lends the entire film a certain unreality that abets its game of twisted perceptions. And these perceptions begin and end in the rather terrible little studio that employs Jack Terry. Jack exudes intelligence in a very humble way, ostensibly in line with his self-description as "the guy who always put together radios as a kid, always won science fairs ... you know the type." He is also young, handsome, and almost suspiciously genuine, which means he must inevitably be sheltering a memory of great embarrassment or regret. He will reveal that regret much later in our film, in a passably convincing scene that also explains why he has relegated himself to the orchestration of slag-ridden grindhouse. I say "passably" because considering how much thought was put into making Blow Out, the motive behind Jack's series of unfortunate acts of kindness and interference will strike the viewer as plucked from a rather dusty hat. What acts of kindness, you ask? Well, what would the average citizen do if he saw, on a dark and lonely night on a dark and lonely park bridge, a car skid off the road into a lake? But since Jack Terry has been out all that evening recording nature's music for his sonic arsenal, he will have something more to do once he has fished the requisite damsel in distress (Nancy Allen) out of the drink.

The damsel in question is Sally, and she doesn't fool us one bit, but she certainly deceives poor Jack. Sally is the type of girl men should always avoid, not because she is insincere, manipulative, or incredibly boring – although all these epithets do apply – but because she is frail and suggestible. Like Jack, she has no ambition or plans in life; but unlike the young man who rescues her, her moral weakness allows her to be cast in other people's plots, most notably those of the inscrutable paparazzo Manny Karp (Dennis Franz). Why doesn't Jack see what is so clear to even the most naïve of onlookers? To his credit, we are privy to one piece of information that is only revealed to Jack much later on: he was not the sole witness to the car crash. So as Jack, roused to action, races to the lake to plunge for survivors, we see another figure racing up the stairs behind him. We also see that Sally was not alone in the vehicle (when Jack approaches the sunken car, a bloodied male corpse greets him from the front seat). But when Jack emerges from Sally's hospital room to find a mass of policemen walling off a throng of reporters, he learns that the other occupant of that car was the governor of the state of Pennsylvania, a strong Presidential hopeful who, at last Gallup auscultation, was more than three times as popular as the incumbent to the Oval Office. Alas, on that fateful eve, Jack was too busy organizing his wares ("strangling victims," "footsteps," "cries for help," and one of the most nonsensical horror movie staples, "knife slices") to notice the evening news piece on Governor McRyan's intention to announce his candidacy. Why would McRyan, on a night when he knew he would draw significant media attention, choose to spend that night with a woman who was not his wife? Is this his form of stress relief? What Jack also did not notice on that same news program is the President's spin doctor, who guarantees his man will prevail come November and gives the camera an unmistakable look – and we should stop our insinuations right there.

The film's title refers to the lakebound car's tire (which recalls this infamous occurrence), just as Antonioni's film, a work based on this short story, refers to a photograph; but the more immediate precursor to Blow Out is this masterpiece about another sound man. Thankfully De Palma's vision lacks both Blow-Up's pretentiousness and Harry Caul's overwhelming guilt. Jack Terry is both exactly what he seems to be and, in a very plausible way, a little more than that. The façade he erects and defends against all who approach him noticeably wavers in Sally's presence, a curious matter since she is hardly what one would call a knockout. More likely, the deed of saving a person's life has imbued the savior with more faith in our earthly existence than it has the saved. So when Jack comforts a mistrustful and confused Sally in the hospital, he does so in a manner almost unique to a young Travolta, in the soft, warm, yet still macho way of someone who could truly care for a stranger because that's what good people do. And when he tells Sally that since he saved her life, the least she could do is have a drink with him, the mild emotional extortion has the pungency of truth. Yet the best scenes involve the world Jack creates in his mind, the marriage of sound and sight (it betrays little of our story to mention that a film of the incident surfaces), coated with the memories of that inexplicable accident that could just as easily have left no survivors at all. One wonders whether Jack's aims and energy would have been the same if it had been his state's governor he had saved, not an average, lonely woman doing average, lonely things with quite possibly the next President of the United States. Maybe Jack Terry would even have been given an award for being such an exemplary citizen. An exemplary citizen, mind you, who spends his nights walking around and recording all the secrets of our universe.